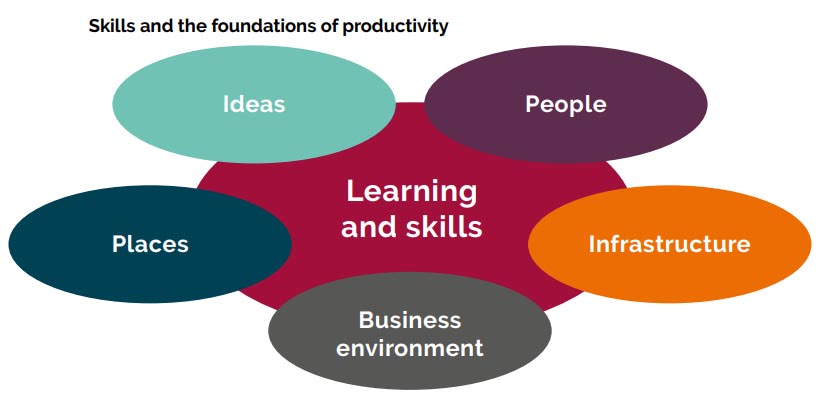

Ten year plan for basic and intermediate skills could boost our economy by £20 billion per year and improve social justice

New research from Learning and Work Institute shows progress improving skills has slowed over the last decade:

A renewed focus on basic and intermediate skills could boost our economy and improve social justice.

Around ten years ago I was working on the Leitch Review of skills, a government-commissioned independent review of the UKs skills needs and how to meet them. It argued we needed to set a higher ambition, particularly focused on basic skills like literacy and numeracy and intermediate skills.

It set ambitions to do this by 2020, underpinned by reforms to build a culture of learning, improve access to learning and engage employers – all essential so that an expansion in learning made a real difference to our economy and people’s lives.

Fast forward ten years and how did we do?

The good news is that our qualifications profile has improved: the consensus around expanding higher education may have somewhat frayed, but participation levels in the UK are not unusual by international standards.

Our challenge is less about numbers in higher education, more about types of higher education and lack of opportunities to learn throughout life.

The bad news is that a new report from Learning and Work Institute shows progress on basic and intermediate skills has almost stalled.

These are the two areas where Leitch said we should accelerate progress, instead we have slowed down. And the less said about all the other actions that were about trying to build a culture of learning and an environment to boost skills utilisation the better – these were essential to ensure improvements in skills benefited employers and people.

This has huge implications for both economic growth and social justice. The Great Recession following the financial crisis has been followed by a Great Stagnation in economic growth, which independent forecasters suggest is now a permanently lower speed limit for our economy.

Over time, this adds up to huge differences in people’s living standards and the amount of money available for public services.

Setting a higher ambition

None of this is either unavoidable or inevitable. Our report sets out a higher ambition, which would see three million people improve their basic skills over the next decade and 1.9 million to improve their intermediate skills.

That’s ambitious, but would return adult attainment roughly to levels seen in 2010. Delivering this could boost our economy by £20 billion per year and support an extra 200,000 into work, doing so in a way that improves social justice.

How do we make this happen?

At the launch event for our research, Robert Halfon, Chair of the Education Select Committee, argued for a ten year plan for education:

- How do we convince the Treasury and wider society of the need for that?

- What lessons can we learn, for example, from the consensus that was built around the need for us all to save more for our pensions that led to auto-enrolment?

- Beyond that, how would we deliver a higher ambition?

New research from the Resolution Foundation, “Pick up the pace: the slowdown in educational attainment growth and its widespread effects” adds to the picture our report paints.

New research from the Resolution Foundation, “Pick up the pace: the slowdown in educational attainment growth and its widespread effects” adds to the picture our report paints.

It shows how the current slowdown in skills varies by sector, geography and background. We already knew that already highly skilled workers are far more likely to get training at work than those with lower skills. But its striking that employers in sectors reporting higher skills gaps are less likely to offer training than those with lower skills gaps.

To some extent this is also not surprising (assuming we think training can help to reduce skills gaps). But it points to the challenge we face and how it varies by sector and group.

In my view, any ten year plan needs to aim to increase participation and attainment in learning by cutting gaps in participation by region, group and sector. This should be the litmus test for a new strategy and new policy.

We need acceleration at all levels, a point emphasised by Sam Gyimah, the former Universities Minister, at the launch of the Resolution Foundation report:

We need acceleration at all levels, a point emphasised by Sam Gyimah, the former Universities Minister, at the launch of the Resolution Foundation report:

“We shouldn’t just trade off more of one type of learning against less of another.”

Basic Adult Skills

Any higher ambition would surely require a real push on adult basic skills, participation in which has fallen by one third in the last decade. Nine million adults lack these skills across England, and they are fundamental to life and work as well as building other skills. We also need to look at the operation of the Apprenticeship Levy.

The Levy is a bold and positive step, but we need reforms to better underpin quality and access in apprenticeships and consider the case for widening its remit to include support for technical education for example.

We also need to support people to learn throughout life. We’ve argued for Personal Learning Accounts, to put people in charge and give a new vehicle to increase investment in learning.

I think the scale of the challenge and the prize from doing better is clear. A higher ambition can’t just be about numbers and targets.

There’s lots of ideas for making a difference, but we need to work together to build a consensus.

There’s a reason we called our report Time for Action.

Stephen Evans, Chief Executive, Learning and Work Institute

Responses