Skills for Green Jobs: a vocational outlook on ecological learning in the arts

#GreenSkillsWeek2021 – Way back before the world changed and we all started wearing strange masks, in the dim and distant past of 2019, students around the world were taking to the streets in their thousands to protest about the need for education to reflect and address the climate and ecological crisis.

It seems like an age ago now that Greta Thurnberg was making headlines and Extinction Rebellion were blocking bridges. The Covid Pandemic changed everything, and understandably became the chief focus of the media and many people’s concerns.

Sadly though, the climate crisis did not go away, and as many people, students included are still pointing out – we still need to address this as a matter of urgency and survival.

The student led movement ‘Teach the Future’, for instance, are still very much active, and are claiming that “Students aren’t being prepared to face the effects of climate change, or taught to understand the solutions”.

What do we need to do to help our students face this future in a meaningful and significant way?

Despite there being many excellent educational initiatives to address this that I can think of (and no doubt many more of which I am not aware), overall, I would say these students are right, and so I find myself asking “what do we (educators) need to do to help our students face this future in a meaningful and significant way”.

This is a challenging question indeed, and I find that the deeper I look into it the more complex and profound the question becomes. It is especially challenging because nobody really knows what the effects and extent of climate change will be in our students’ lifetimes.

I’m not sure most of us, myself included, fully grasp what the solutions are, or what changes those solutions require of us as a society and as individuals. As challenging as it is though, I am convinced that working to provide an education that meets the needs of our students to face this future is an absolute priority for all further education.

‘Skills for Jobs’ not ‘a sustainable future’

Quite recently I read through the latest government white paper on the future of further education; “Skills for Jobs” to see if this sense of priority was a part of their vision. I was pleased to see that “our commitment to net zero” and the importance of preparing students for “the green economy” was mentioned, however, I was somewhat dismayed to see that these points are not elaborated further, nor are they central to the propositions put forward, and in fact there is no further mention of the climate and ecological crisis we are facing, and how it will shape and impact upon all our futures.

I understand of course that the title and remit of the paper was ‘Skills for Jobs’ and not ‘a sustainable future’; but here is my point, the jobs and the industries that we create in the near future, as a society, will significantly shape and be shaped by the climate and ecological changes we have set in motion.

We are living in a time when we have witnessed and actively caused the loss of 68% of global biodiversity over the past 40 years, and are on course to significantly accelerate this rate of change. Our own government has set a target of net zero emissions by 2050 in an attempt to limit catastrophic climate change to the 1.5 degree average increase in global temperatures.

The sheer scale of the societal and industrial changes we need to make in order to effectively meet these challenges, let alone restore the damage already done to essential life support systems, means that practically every area of industry will need to be transformed into something radically more sustainable.

I would have thought then, that any white paper on ‘Skills for Jobs’ and the future of further education would significantly reflect the radical transformation that we need.

What is needed to make this transformation in further education?

My purpose here, however, is not solely to critique the aforementioned white paper, especially when, as an educator, I agree with much of it’s proposals for enhancing the employability of our students. Instead, I want to look at what is needed to make this transformation in further education.

Perhaps though, ‘the problem is the solution’. Perhaps we can create vocational learning and skills building opportunities which address and are informed by ecological transformation.

The International Baccalaureate Environmental Systems & Societies students visit the site of reintroduced beavers as part of the Green Minds project

This is something that I, for one, have been working to create opportunities for at Plymouth College of Art’s Pre-degree faculty for a number of years. Just recently, for instance, I have been working with Plymouth City Council, as part of the city wide urban rewilding project ‘Green Minds’ to create live client briefs for design projects for our students.

This includes exciting project opportunities such as creating information interpretation display material for a visitor centre for the UK’s first urban beaver reintroduction programme at Poole Farm, with opportunities for outdoor sculpture, murals and AR material around the farm.

There also is the opportunity to create web and printed promotional material, wildlife filming and footage editing and documentary work for environmental enrichment work in the city’s Central Park, and many more such collaborations planned for the future also.

Our pre-degree faculty runs courses in Graphics, Illustration, Game Arts, Photography, Fashion and Textiles, Art & Design and Performance and Production Arts; and there are opportunities for students from every one of our courses to get involved with this project.

Each year, all our vocational UAL Extended Diploma courses are given an assignment brief in the first year that asks them to consider and produce work concerning sustainability through their subject specialism. Many of these assignments have involved live client brief work, with collaborations including local environmental organisations such as The Devon Wildlife Trust, The National Marine Aquarium and Regen South West.

The running of sustainability themed assignments has enabled us to deliver relevant teaching on climate and ecological issues, whilst clearly linking this to their professional development and future facing outlooks. In addition to these opportunities we present on our UAL Extended Diploma courses, we also run an International Baccalaureate Career Programme.

This programme includes a healthy amount of ethical and critical thinking skills. It allows students to broaden their academic achievements with IB Diplomas (I run the IB Diploma in Environmental Systems and Societies, for instance) and also further augments their employability and citizenship skills with a ‘Service Learning Programme’ which includes 50 hours of community service.

Combined focus of employability skills and ecological learning

There are other benefits to our combined focus of employability skills and ecological learning; It makes climate and ecological action more accessible to our students. It gives agency and empowerment to our students to use their unique skills, to be ‘a part of the solution’. From a teaching perspective, it encourages ‘buy in’ to the learning from those of our students that might also see environmental action as of low personal or vocational relevance.

I say ‘also’ here, because I believe that this viewpoint is also shared and passively promoted by the hitherto underwhelming action of the UK’s national education strategies from our governmental, awarding and quality monitoring bodies to (not) bring climate and ecological action into the heart of our future facing FE curricula.

This is harsh criticism, I know, and I also know there are many excellent and inspirational initiatives within the sector, and yet still, nationally speaking, I believe we are falling short of what is needed.

Shouldn’t vocational skills for the green economy be addressed through STEM subjects?

You might be forgiven for reading this article and thinking that addressing the need for ‘green’ skills for jobs in the context of an arts curriculum is not the best example of my point. Surely, you might think, for instance, vocational skills for the green economy are best addressed through STEM subjects, through engineering perhaps, or through training for jobs in renewable energy systems.

Well sure, yes, those subjects are of vital importance to the green economy, but also, and this is crucial; every area of vocational and academic education has a role in helping our society transform from an ecologically destructive paradigm into a regenerative and restorative culture.

The arts certainly have a key role in this. Art has always reflected and influenced the moral, intellectual and social values of society. Over the past 500 years, our ‘western’ civilization has developed a socio economic structure, with a belief system which is founded on the extraction and exploitation of ‘natural resources’.

We extract, exploit, consume and dispose of resources in a linear fashion that is completely at odds with the cyclical and interconnected systems of the natural world, and is equally antithetical to many more sustainable indigenous societies.

Our visual artists, for instance, can communicate; not just the information and practical solutions to our ecological emergencies, but also values and awareness of the very different and more regenerative culture that I believe is beginning to emerge in our increasingly ecologically aware society.

Art speaks to the heart

Art speaks to the heart, you might say, and there is plenty of evidence to suggest that it is as much emotional connection as intellectual understanding that influences our (people’s) environmental behaviour.

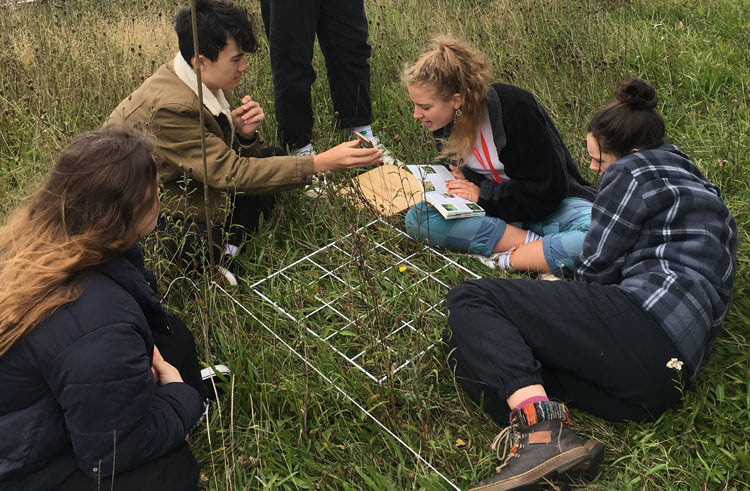

Students take wildflower and plant surveys to help rate environmental value systems on a slide scale

I am not suggesting that this preparation and learning for climate change and ecological restoration can be entirely delivered through vocational skills and work experience. I believe It is an important focus, yet also, to truly transform those cultural values, the thought processes and lifestyles that our ecologically dysfunctional society fosters, we need more.

We need to know our environment, and the interconnected nature of life itself through our emotions and our senses. We need to learn about our relationships with our ecosystems through lived experience.

Experiential learning, observational skills, bioregional knowledge, critical thinking, social, ecological and emotional literacy are all facets of the learning that is needed; and yet more that I and many other such teachers, who are ourselves just learning, have still yet to learn.

I do think however, that vocational learning is a great place to start, and of vital importance to Further Education.

So what is needed then, from our educational institutions to support these demands?

What actually needs to happen? Is it a case of lots of ecologically motivated teachers needing to find ways to make vocationally relevant skills and learning opportunities happen? That will help for sure, but we need structures and incentives to support these innovations.

Otherwise, those learning opportunities we create will be entirely dependent on the ever changing motivation levels and capacity of individual teachers. What is set up one term, might simply not be continued another, as priorities and situations change. From 15 years of teaching experience, I have seen budgets become increasingly and perennially tight in Further Education.

Much the same can be said for our workloads and the plethora of extra criteria and considerations we seem to be required to meet every year. It is easy then, for sustainability to seem like just another external pressure, another trendy buzzword we feel we ought to engage with but really don’t have the time for. It is often a similar picture with FE students.

The short time they have for transitioning from childhood and home to being fully functioning income earning adults can mean therefore that their overriding concerns are simply to meet the unit criteria of their qualifications and to get good grades.

Saving the planet, or helping the nation build a green economy can appear way down the list of priorities – especially given the pressures on mental health brought by modern society, and more recently the coronavirus pandemic.

What we really need, and what I need as a teacher to help me do my bit, is more leadership and incentives from the system I work within:

- What if Ofsted and Ofqual, for instance, were to set stronger requirements for all curricula to focus toward this green recovery?

- What if all qualifications included and accredited this learning?

- What if our students, simply by doing their studies and learning their trades, were being prepared to “face the effects of climate change”, and “taught to understand the solutions”?

- What if all teachers were given training and support to help their students face this future?

- What if our government wrote educational strategy papers that were a little less white, and a little more green.

I think that would help.

By Chris Smith, UAL Level 2 Art & Design Subject Lead, and the Tutor for IB Environmental Systems and Societies at Plymouth College of Art

Responses