Apprenticeship policy in England ‘requires improvement’

Hundreds of delegates recently attended the Future of Apprenticeships #FoA2020 online conference, produced by #SkillsWorldLive for the Federation of @AwardingBodies. Tom Bewick reflects on the day and argues that more impetus is needed to recalibrate England’s apprenticeship model:

If you were applying an endpoint assessment to the apprenticeship system in England, what grade would you give it?

Fail, Pass, Satisfactory, Merit or Distinction?

When I put that question to the minister for skills and apprenticeships, Gillian Keegan MP, she refused to be drawn on awarding an overall grade. The minister was prepared to say, however, that the ambulance sector deserved a ‘distinction’ for all their sterling work. Meanwhile, the boss of the quango set up to be the main guardian of the country’s apprenticeship model, Jennifer Coupland, was more emphatic. She described the reformed apprenticeship system, which she has helped to develop since 2012, as worthy of ‘merit.’

Questions like this are important to ask of leaders; as well as public bodies like the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education (IfATE), because they reveal the extent to which there is some degree of self-awareness and critical evaluation going on.

Jim Collins, the author of the bestselling management book, ‘Good to Great: why some companies make the leap and others don’t’, reminds readers that: “Greatness is an inherently dynamic process, not an end point. The moment you think of yourself as great, your slide toward mediocrity will have already begun.”

It’s why, at best, I would award an EPA of the apprenticeship system in England as a standard ‘pass’ at this present time. Moreover, if I were carrying out an Ofsted inspection of the underpinning institutions, like IfATE, I would most probably rate them as ‘requires improvement.’

Of course, these are just my personal opinions at the end of the day. That said, when you examine some of the hard metrics underpinning England’s apprenticeship model in recent years, you have to wonder whether an independent assessor might come to a similar conclusion.

Policy doesn’t have the equivalent of an apprenticeship assessment plan. But we can test the policy performance of apprenticeships in England against the ambitions set out in government documents; as well as analyse the extent to which the vision and objectives contained within them have been met.

Let’s imagine, for a moment, that there was such a thing as an external quality assurance (EQA) body for the performance of apprenticeships policy! It might read something like this.

Classic mission drift?

Eight years on from the Richard Review (2012) and we are still banging on about many of the same issues that policymakers were back then. The diagnosis at the beginning of the last decade included not enough employers engaging in the programme. Even back then society had a strong belief that more young people could be doing apprenticeships instead of going to university. The big red flag was the feeling that the quality of apprenticeships was suffering because of some sharp practice in the marketplace and programme participants, including employer training providers, not being sufficiently regulated. To many operating in the system currently, this will feel like Groundhog Day.

The entrepreneur, Doug Richard, asked of apprenticeships policy, essentially, three fundamental questions. What are they for? Who are they for? And how should they be assessed? On the first of these questions, Richard concluded that apprenticeships were mainly new job roles; usually entry-level roles; and that most apprenticeships should have a focus (if not exclusively) towards younger people.

As Richard Marsh, from Kaplan Financial, revealed in his knowledgeable presentation at the #FoA2020 conference – looking at the history of apprenticeships policy in England – a real tension continues between youth employability aims and higher skills productivity (or employer recruitment behaviour) preferences in the UK. In Germany and Switzerland, the purpose of apprenticeships are much clearer: they are for people predominantly under the age of 25.

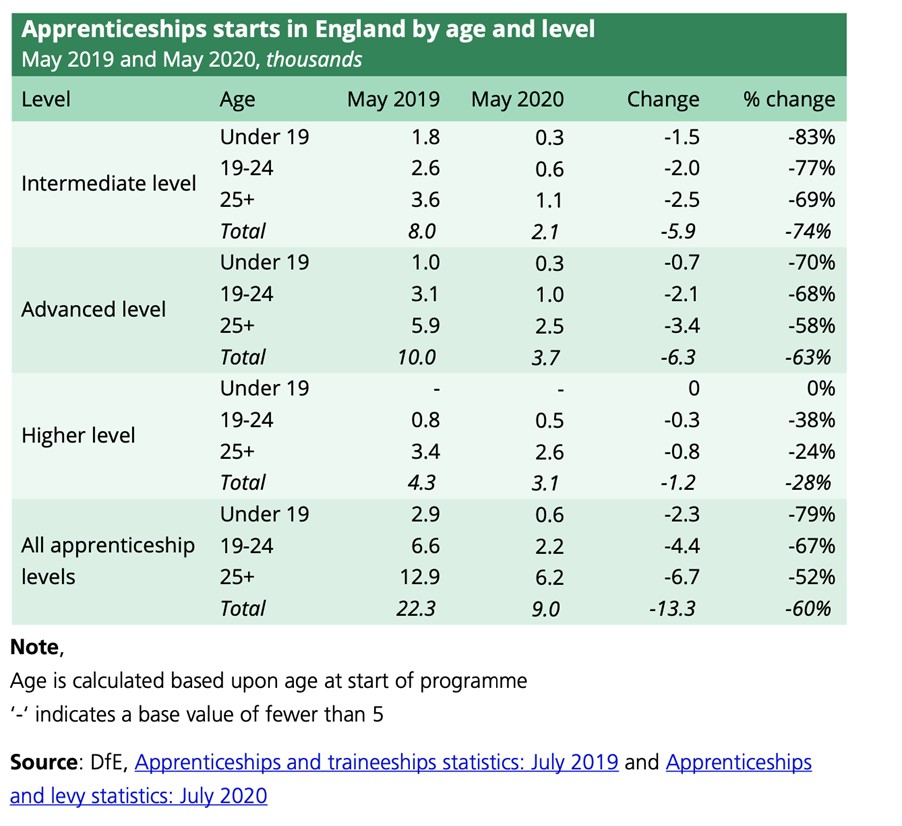

Germanic system employers have created entry to intermediate level roles, (and as part of a longstanding culture of employer recruitment), that aims to build a systemic pipeline of talent into occupational sectors and industries. The data shows that at least two-thirds of teenagers enter apprenticeship each year in Switzerland, compared to just 8 per cent of 16-20 year olds in England. Two thirds of over 25-year-olds, mainly existing employees, now make up the profile of England’s apprenticeship model. This increase in older apprentices predates new standards, although recent House of Commons research (August, 2020) has found the biggest increase in new starts going to those aged between 35 and 44 years old on the new standards. (See Table 1 below). Moreover, the majority of new starts are now at advanced and higher-level, raising fresh doubts about the extent to which they are promoting a ladder of opportunity amongst individuals with lower levels of prior attainment.

Table 1

It is hard to find any published figures on this, but it is reasonable to assume that many older apprentices have already achieved a taxpayer supported first degree (worth around £63,780 per undergraduate student). It begs a really thorny question of whether we are, in fact, drifting completely away from the original policy intent of the Richard Review? Even in the government’s 2015 publication, Vision 2020, ministers were still promising the reforms would deliver many more opportunities for young people to get a foothold in the labour market via the apprenticeship route. Yet, this manifestly has not happened.

Several years on from these bold ambitions, opportunities for younger apprentices are at their lowest level since comparable records began. Indeed, the mean average age of the programme has extended by more than 3 years since the 2017 Apprenticeship Levy was first introduced; with many of the participants benefiting the most already being quite highly-skilled (e.g. management apprenticeships). Similarly, the geographical profile of apprenticeships has shifted over time from the post-industrial north of England to the service-dominated south. The diversity profile of the scheme broadly reflects the gender and racial inequalities of the wider labour market. Taken together, all these factors add a whole new meaning to the term ‘levelling up.’ Those who appear to already get some of the best training opportunities in the workforce, are now securing access to even more state funded provision, by achieving ever higher levels of apprenticeship support.

Despite the obvious mission drift of the programme since 2012, the debate at #FoA2020 found widespread support for ministers in England to continue with an all age, all levels apprenticeship model. What delegates wanted to see, perhaps, was a better, finer-tuned incentive structure; and more targeting of apprenticeship roles at younger people entering the jobs market for the first time. The most common feedback in the interactive chat sessions and during the livestream debates, was the nagging doubt about whether the current employer financial incentives regime, actually struck the right balance. And, in particular, whether the current incentives are enough for encouraging more employers to take on younger people over the next year as a result of the pandemic.

For example, how can a £2,000 apprenticeship cash incentive, paid in arrears, for a 16-19 year old apprentice, compete with a £6,000 wage subsidy for an unemployed 24-year-old graduate via the Kickstart jobs scheme?

Meanwhile, in Australia, the federal government has moved far more aggressively; and set aside $1.2 billion (c. £663 million) over the next year to specifically provide apprentice wage subsidies for new hires, with financial support up to 50 per cent of the total cost to employers.

Missing the targets and missing the point?

Just about every apprenticeship and workforce training target the government has set in the past decade has been missed. It includes the government’s own public sector targets to ensure at least 2.3% of new hires are employed via an apprenticeship route. The latest research shows that only 1.6% of public sector staff are apprentices during the reporting year, with many Whitehall government departments and agencies in the slow lane.

In the wider economy, general training investment in employees has gone into terminal decline. Compared to our main international competitors, the UK suffers from chronic workforce underinvestment. The austerity cuts to the public side of ledger have probably not helped, as adult skills provision has eradicated over 2 million opportunities. Overall, UK productivity has improved by only 4 per cent since the global financial crisis. In 2009, Australia trained 39 apprentices in every 1000 persons employed. In Germany, the corresponding figure was 40. At that time, England was training just 11 apprentices per 1000 people employed. With the recent collapse in apprenticeship starts, this already below par performance internationally, may have spiralled downwards even further.

The government’s manifesto and statutory target of 3 million apprenticeship starts by 2020 was missed by a country mile. The government would say that its focus now is on quality, not quantity. Here, however, the performance story is patchy. There is no doubt that the introduction of new standards and the independent system of end-point assessment has raised the status of the programme in the eyes of many apprentices and employers.

The Federation of Awarding Bodies publication, ‘Quality in Apprenticeships’ documents where many of these improvements have already taken place. The biggest win has been the introduction of an independent check on apprentice competence; the knowledge, skills and behaviours (KSBs), taught by providers and employers.

Canada is the only other country to offer this approach. As a result, the federal government’s ‘Red Seal’ programme is extremely well respected and crucially, allows skilled tradespeople across Canada to work on an inter-provincial basis, without the need for additional certification. Importantly, Red Seal avoids a potential patchwork of competency-based standards emerging, thereby sowing even further confusion amongst employers.

In many ways, we urgently need to develop a UK-wide version of the apprenticeship Red Seal programme, as currently, a butcher’s apprentice in Dundee, for example, is not necessarily being trained to the same apprentice workforce standard as an apprentice butcher in Devon. In highly localised labour markets this may present less of a problem. But how does a cyber security firm in Wales know whether someone qualified in England has the equivalent knowledge, skills and behaviours?

As the government’s internal markets Bill passes through the UK Parliament, it is increasingly apparent of the unintended consequences for job prospects and skills markets of allowing post-compulsory education and training policy to be fully devolved; including the costly bureaucracy of parallel skills initiatives being set up in England’s mayoral combined authorities (MCAs).

As with social security and state pension provision, there is a strong rationale for making skills and apprenticeship policy a UK-wide competence (at least for the occupational standards and skills entitlement elements), even if such a move would be hard to deliver politically.

A system that lacks transparency?

I’ve lost count of the amount of times people in the sector contact me to complain about the lack of transparency of the various skills quangos they have to deal with. The public has gained an insight into this challenge through the work of the Education Select Committee, chaired by Robert Halfon MP.

To the annoyance of many cross-party MPs, the summer exams fiasco was a prime example of high-paid senior individuals and organisations “going to ground” whenever difficult challenges or questions were presented to them. It would be a mistake, in my view, to think that this lack of transparency or the public accountability challenges was only confined to the Department for Education and Ofqual.

The apprenticeship system still has a mountain to climb in terms of the data made available about the detailed and actual performance of the apprenticeship programme. Ofsted data and published reports can tell us a lot about what is happening along the apprentices’ journey up to the point of the so-called Gateway (the point at which an apprentice can be submitted for an EPA). After the Gateway, a whole panoply of performance data currently sits shrouded inside a policy black box.

It is simply not possible for the public to access data that will tell them, for example, by EPAO, how many EPAs have been conducted by that organisation; what the pass rate was like compared to competitor EPAOs; or whether any quality issues have been identified by the external quality assurance (EQA) body. The IfATE and the Education Skills Funding Agency (ESFA) do hold a range of performance dashboards and management information about the quality of the system, although to date, they have chosen not to place very much of it in the public domain. For a taxpayer funded apprenticeship delivery model, this level of opaqueness and general lack of transparency is unacceptable.

Conflicts of interests abound?

A lack of transparency leads inevitably to allegations of conflicts of interest. We’ve seen instances of Trailblazer group members sitting on the boards of apprenticeship training providers and EPAOs, sometimes operating as paid consultants and commercial advisers.

The whole point of the Richard Review reforms was to end the widespread sense that people were too often able to ‘mark their own homework’, particularly by having a material interest in the outcome of the apprenticeship itself. It doesn’t feel wise or sensible to allow inter-company or personal business relationships to develop that, if they were being monitored by the Financial Conduct Authority, for example, they might reasonably pass the threshold for claims of ‘insider trading.’ Eight years on, England’s apprenticeship model is still dogged by these kind of accusations. Whether conflicts of interest are real or perceived, they can have a debilitating impact on the integrity of public policy where they are not robustly dealt with or kept in check. The Nolan principles of public life have been around for a long time. They are, in many ways, the gold standard the sector should be aspiring to.

When Doug Richard talked about the need for a clear separation between those providing apprenticeship training and those delivering the independent end-point assessments, I doubt very much that he envisaged a situation where universities would be allowed to mark their own homework in apprenticeships by setting up their own EPAOs.

Is the Levy a ‘failed experiment’?

The Prime Minister’s skills adviser, Baroness Alison Wolf, was in many ways the architect of the Apprenticeship Levy. She first called for the payroll tax in a report for the Social Market Foundation in 2015. To the surprise of many commentators, the Conservative government (not usually associated with new ‘taxes on business’) announced a levy on large firms with payroll expenditures above £3 million, netting around £2.8 billion per annum UK-wide.

Wolf would later tell the Education Select Committee that she thought the levy scheme should be extended to smaller firms so that all employers, whether they took on apprentices or not, had a stake in contributing to a national pot. The latter recommendation, had it been implemented, would certainly have taken off the subsequent pressure of an overspend in the apprenticeship budget. In December 2018, the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education started to warn of an imminent overspend in England of £500 million in the earmarked budget, rising to £1.5 billion during this financial year. Ironically, the types of companies worst affected and unable to access funds to recruit apprentices was SMEs. Meanwhile, large employers have consistently complained about the lack of flexibility.

With the number of starts plummeting since the levy was introduced and the recent impact of Covid-19, the budget has flipped the other way, into an underspend scenario. It has led to the outgoing director-general of the CBI, Carolyn Fairburn, describing the scheme as a “failed experiment.” The big bosses lobby group would like to see the levy reformed to allow large employers to use their digital accounts for more general upskilling and retraining opportunities. The Association of Colleges has suggested the underspend is used to fund the increase in 16-19 year olds that are staying on in full-time education as result of skyrocketing youth unemployment due to the pandemic.

The problem with all these suggestions is that fundamentally they undermine what the levy was designed for: to help and incentivise employers to take on more apprentices. By not using the funds earmarked for this purpose, it suggests other barriers (perhaps cultural, policy and financial) are still preventing more firms from taking part. If the Levy was extended to all firms with a payroll in excess of £1 million, would more firms hire apprentices? The experience to date would suggest that there are other, more complicated demand-side factors at work, than just the availability of access to apprenticeship funds.

Is it time to re-calibrate England’s apprenticeships policy?

It feels hard not to conclude, from this analysis, that England’s apprenticeship policy has lost its way in recent times. The programme no longer acts as a major route from the upper secondary phase of education into skilled employment. The people securing apprenticeship are those mainly already in work, casting doubt on the idea of apprenticeship as the route to mastery in a new occupational field.

A more accurate description for the scheme, as currently constituted, is that apprenticeships in England have evolved into something more like a national retraining programme for those in their late-20s to mid-40s, whose employers like the idea of subsidised and structured learning, leading to a nationally recognised competency-based exam.

Indeed, research shows that the independent and robust nature of end-point assessment appears to be the one Richard Review reform that has proven relatively popular. In many ways, EPA may turn out to be one of the more enduring aspects of these reforms.

Despite this, a majority of apprentices say that they feel ill prepared for the demands of end-point assessment, as both provider achievement and completion rates have fallen, particularly in relation to the new apprenticeship standards, compared to the old frameworks. There’s a chance that all these challenges are just the teething problems of a reformed apprenticeship model, in operational terms, still less than four-years-old.

As several contributors mentioned at the Future of Apprenticeships conference, we may have to be a lot more patient and simply persevere with what we’ve got. But equally, policymakers may have to go back to basics once more, asking what and who apprenticeships are for. In future, this could lead to another wholesale recalibration of England’s apprenticeship model; not least to ensure more young people (under 25) are able to take part.

Tom Bewick is the chief executive of the Federation of Awarding Bodies and the presenter of the Skills World Live radio show at FE News. He recently hosted the www.futureofapprenticeships.com digital conference with other sector leaders.

Responses