The impact of the levy on apprenticeship quantity. Part 1

This is part 1 of a daily analysis of the Reform report on the Apprenticeship Levy that FE News are running this week.

The levy formally came into force on 6th April 2017. To assess the impact of the levy, the first consideration is whether there has been a rise or fall in the number of people starting an apprenticeship since its introduction. After explaining how the levy works in practice, we will explore the data published by the Government on the number of ‘apprenticeship starts’ since April last year as well as analysing the ages of those starting their training and the level at which people are training.

How the apprenticeship levy works

Any organisation with an annual wage bill of over £3 million (approximately 2 per cent of all employers) must report and pay their levy – at a rate of 0.5 per cent of their pay bill – to HMRC through the PAYE system. This applies to employers in all sectors, including public sector bodies and charities. Each of these employers has access to a ‘digital account’ with HMRC that holds their levy contribution, which is updated on a monthly basis and includes a 10 per cent top-up to their accounts provided by government. The funds stay in an employer’s digital account for up to two years before they expire.

Once an employer decides to take on an apprentice, there are a number of steps required for them to draw down their levy funds:

- Choose which ‘apprenticeship standard’ (i.e. training course) they want their apprentice to work towards.

- Select a ‘training provider’ from a list of organisations approved by the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA).

- Select an ‘assessment organisation’ approved by the ESFA to carry out the final assessment at the end of the apprenticeship.

- Agree a price for each apprenticeship with the training provider, which includes the costs of training and assessment.

- Pay for training and assessment with funds through their digital account.

Each apprenticeship standard is placed into one of 15 funding bands, with the upper limit of those bands ranging from £1,500 to £27,000. These bands were introduced by the Government as “setting an upper limit on the amount spent on an individual apprenticeship ensures that public money is spent in an appropriate way and achieves maximum value for the taxpayer.” In line with the Richard Review, the government guidance for levy-paying employers also maintained that they “are expected to negotiate a price for their apprentice’s training and assessment.”

If an employer does not pay the levy then they must still choose an apprenticeship standard, training provider and assessment organisation. However, the absence of a digital account means that they simply pay a ‘co-investment’ of 10 per cent towards whatever price they negotiate with the providers and the Government will then directly pay the provider the remaining 90 per cent. The same applies to a levy-paying employer who has used up all of their levy funds in a given month.

The levy system has other nuances. For example, employers with fewer than 50 people can train 16 to 18-year-old apprentices or those aged 19 to 24 who have previously been in care or have a Local Authority Education, Health and Care (EHC) plan without paying the 10 per cent co-investment – meaning that the Government foots the whole training bill.

Employers who take on apprentices aged 16 to 18 receive £1,000 to help meet the extra costs involved while training providers also receive the same £1,000 payment for supporting apprentices who are aged 16 to 18 or aged 19 to 24 and are either a care leaver or have a Local Authority EHC plan.

Falling apprenticeship starts

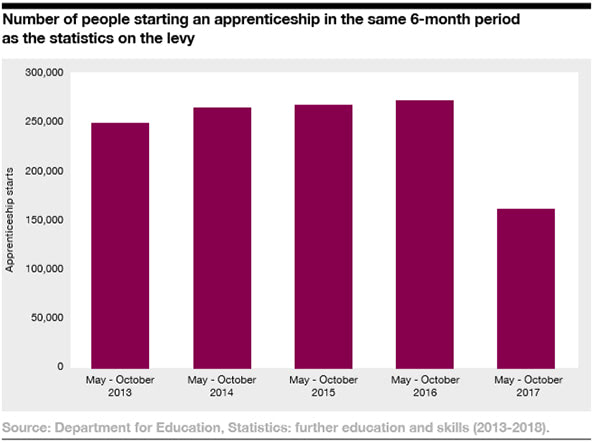

Government statistics show that the number of people starting an apprenticeship from May 2017 to October 2017 (the 6-month period after the levy was introduced) was 162,400 – over 40 per cent lower than the same period in the previous year.

This graph shows the number of apprenticeship starts in the comparable May-October period in each year since 2013.

The Department for Education (DfE) has also begun publishing monthly updates on the number of apprenticeship starts since the quarterly data covering the period from May to October 2017 was released. The most recent figures fared little better than the previous six months. In November 2017 27,000 learners started an apprenticeship compared to 41,600 starts in November 2016, while in December 2017 there were 16,700 apprenticeship starts compared to 21,600 starts in December 2016.

Even before these figures were released, warning signs had emerged elsewhere. In September 2017, a survey of more than 1,400 companies found that nearly a quarter of those paying the levy had no understanding of it or no sense of how their company would respond to it, and more than half of them said that it represented merely an additional cost with 56 per cent not expecting to recover any or only a part of their levy funds.

In terms of the likely impact on employer behaviour, a CIPD survey of more than 1,000 organisations in January 2018 found that:

- 46 per cent of levy-paying employers think that the levy will encourage their organisation to rebadge current training activity in order to claim back their allowance.

- 40 per cent of levy-paying employers said it will make little or no difference to the amount of training they offer.

- 35 per cent of employers will be more likely to offer apprenticeships to existing employees instead of new recruits.

- 26 per cent of levy-paying employers said it will mean their organisation reduces investment in other areas of workforce training and development.

- 19 per cent of levy-paying employers, including 35 per cent of SMEs, will simply write it off as a tax.

This indicates that, rather than investing in high-quality apprenticeships for young people that aim to train them in a new and skilled occupation, employers were already planning to react to the levy in a very different manner (or perhaps not respond at all).

Changing patterns in the level and age of apprentices

The response from employers is also beginning to change the profile of who starts an apprenticeship. Apprenticeships are almost exclusively offered to young people in other countries such as Germany, Switzerland, Austria and France because it is widely understood that apprenticeships are a form of initial vocational training to help a young person enter an occupation.

In this country the decision to offer apprenticeships to those aged 25 and over from 2004 onwards did not have a noticeable impact at the outset. By 2007 there were still only 300 adult learners starting an apprenticeship each year.

Subsequently, as discussed earlier, there was a sharp increase in the number of adult apprentices (amplified by the transfer of learners from the ‘Train to Gain’ scheme that was being closed down).

In every year since 2011, the number of learners aged 25 and over starting an apprenticeship has been higher than the number of starts among those aged under 19 – with adult apprenticeships peaking at 230,300 in 2013.

Far from addressing this lack of focus on young people in the apprenticeship programme, the levy appears to be compounding it. During 2014 and 2015, the delivery of the new wave of ‘apprenticeship standards’ designed by groups of employers – describing the skills, knowledge and behaviours that an apprentice is expected to acquire during their training – was initially concentrated on younger age groups.

The latest statistics suggest that this is an evolving picture as employers switch their attention to older age groups instead. In the six months of full data available since the levy began operating in April 2017, the age category with the highest number of people starting to train towards one of the new ‘apprenticeship standards’ is the over-25s.

In addition to older age groups becoming the focus, the mix of apprenticeship levels is shifting from Intermediate (Level 2) towards Higher and Degree Apprenticeships (Levels 4-6; equivalent to the first year of university through to a full degree). In established apprenticeship systems such as Germany, Switzerland and Austria, almost all apprenticeships are at Level 3 because the training is designed to ensure apprentices become fully competent in their occupation rather than providing training at higher levels to those already in work.

The proportion of apprenticeships in this country being delivered at higher levels (Level 4+) has grown markedly since the levy was introduced, but just 12 per cent of these have been delivered to those aged under 19. This suggests that more experienced workers are increasingly becoming the focus of the apprenticeship programme, at the expense of less experienced employees.

The changing mix of ages and levels in the statistics on apprenticeship starts are both in line with the aforementioned survey findings that suggested many employers will seek to use existing and/or older employees and rebadged training schemes to draw down their levy funds instead of recruiting new and typically younger people.

By 2020 all apprenticeships will be delivered using these new ‘standards’, which serves to highlight their importance as an indicator of how the levy is likely to affect opportunities for young people. Furthermore, the extent to which government funding generates outcomes that are not additional to what would have occurred in the absence of such funding, also known as ‘deadweight’, looms large.

Before the levy was introduced, apprentices aged 19 and over typically attracted a subsidy of around 50 per cent for their training costs while apprentices aged under 19 attracted a subsidy of 100 per cent. This has now altered so that, while those aged under 19 can still attract the full subsidy, apprentices aged 19 and over are now subsidised to the tune of 90 per cent of the training costs (the employer co-investment rate of 10 per cent covers the remaining portion).

This introduces a sizeable incentive for employers to start training older apprentices, including existing employees, that goes well beyond the subsidies available before the levy was rolled out.

The role of the 3 million target

Politicians from all parties are right to demand a better technical education system in this country, but the apparent targeting of the quantity of apprenticeships rather than the quality and substance of what is being delivered is the wrong approach.

The overall quantity of apprenticeships has fallen and the mixture of the ages and levels of apprenticeships is also changing. The target of 3 million apprenticeship starts by 2020 creates a situation in which the need to support young people into apprenticeships at a suitable level is no longer formally prioritised by the Government. Likewise, the apprenticeship levy is now expected to help deliver more apprenticeship starts in an effort to hit the 3 million target even if those additional apprenticeships are disproportionately taken by older and existing workers.

When the commitment to 3 million apprenticeships by 2020 was first announced, Professor Alison Wolf – author of a major government review of vocational education in 2011 – described it as a “mad and artificial political target which risks undermining the reputation of apprenticeships”.

The NAO subsequently pointed out that the target would not tackle skills gaps or improve outcomes for learners, while the Institute for Fiscal Studies stated last year that “a stronger focus on quality and a policy designed to maximise impact rather than numbers” was needed instead.

The 3 million apprenticeship target is not responsible for every problem facing the apprenticeship levy and its associated reforms described in this report. It is nevertheless driving employers and training providers to accelerate the delivery of new apprenticeship standards before a solid foundation has been placed underneath the reform programme as a whole – particularly, as this report argues, in terms of apprenticeship quality and the validity and reliability of apprenticeship assessments.

To this day, no research evidence has been published by the Government to support the notion that 600,000 apprenticeship starts per year from 2015 to 2020 is appropriate for the economy. Moreover, the incentives that the target has introduced into the apprenticeship system for employers, training providers and assessors will undermine any attempt to either improve the quality and stature of apprenticeships in this country or generate more opportunities for young people to enter skilled occupations.

The target for 3 million apprenticeship starts by 2020 should be abandoned so that the focus can be placed on apprenticeship quality above all else.

Tom Richmond, Senior Research Fellow at the Reform Think Tank

About Reform: An independent, non-party, charitable think tank whose mission is to set out a better way to deliver public services and economic prosperity.

Now that the apprenticeship levy has completed its first full year of operation, last Friday (13 Apr) Reform published “The Great Training Robbery: assessing the first year of the apprenticeship levy” which reviews the available evidence to determine whether the levy will, as the Government hopes, “incentivise more employers to provide quality apprenticeships” and “transform the lives of young people who secure them”.

Responses