Lifelong Learning in Limbo: What Stalling Participation Means for the Future of Skills

Adult learning is essential for helping workers and economies adjust to the intensifying demands of digitalisation, the green transition, and population ageing. New data from the 2023 Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) reveals that, over the past ten years overall participation has stagnated or even fallen in most countries. Contemporary adult learning is dominated by training activities lasting less than one week or even taking place within a single day.

In an era of rapid technological change, ageing and the green transition, economies depend more than ever on adults’ ability to keep learning throughout life. Lifelong learning helps workers stay productive, adaptable and employable; it enables economies to absorb shocks and take advantage of new opportunities. Yet, across most OECD countries, adult learning systems are struggling to keep up with these accelerating transformations.

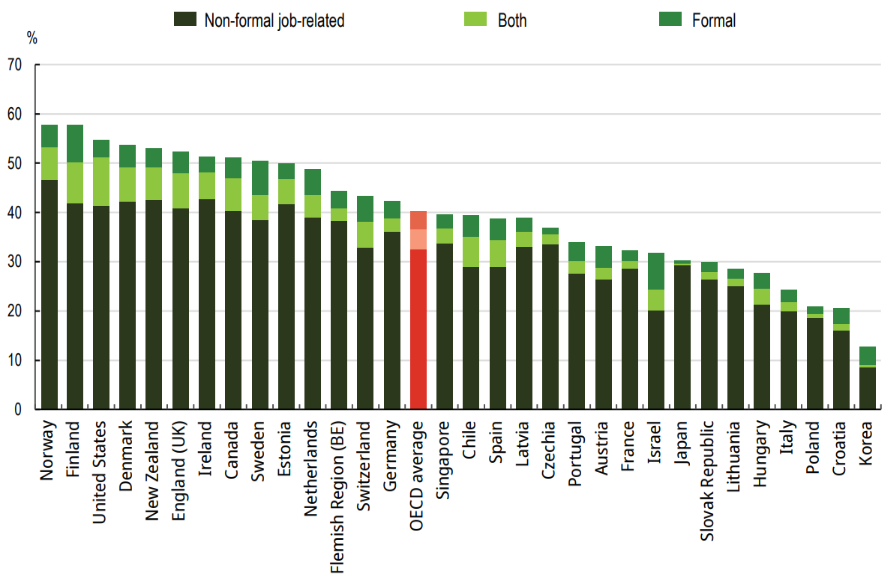

Our new OECD report, Trends in Adult Learning, draws on data from the recent cycle of the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) to track how participation in adult learning has evolved over the past decade. The picture is sobering: around 40% of adults in OECD countries participate in some form of formal or non-formal learning each year – a figure that has barely changed in ten years. In several countries, participation has even declined. And differences between countries are staggering: while over half of adults engage in learning in Finland and Norway, participation remains below 15% in Korea. Aside from some stand-out countries (e.g., Ireland and Estonia have managed to increase participation in adult learning), the overall story is one of stagnation rather than progress.

Adult learning fosters adaptability and productivity growth

Adult learning underpins labour market adaptability, productivity growth and social inclusion. As technological innovation reshapes jobs and tasks, and as ageing populations stretch working lives, workers must be able to renew and expand their skills. Countries that fail to invest in learning opportunities risk lower productivity, weaker innovation and rising inequality between those whose skills remain relevant and those left behind.

This is not just an individual challenge, but a macroeconomic one. The capacity to upskill and reskill determines how effectively economies can respond to structural changes – whether meeting the growing demand for digital and green skills or reallocating workers to new sectors. Without robust lifelong learning, economies become brittle, and workers vulnerable.

Short formats prevail in non-formal learning

Adult learning encompasses a wide range of activities. Formal learning refers to structured education that leads to a recognised qualification. Non-formal learning involves organised courses or training that do not result in a formal credential but are often job-related.

Across the OECD, training is dominated by non-formal learning – organised courses or training that do not result in a formal credential. While only about 8% of adults participate in formal education each year, roughly 37% take part in non-formal learning. High-performing systems, such as those in the Nordic countries and the United States, combine strong participation in both forms, recognising that adults have diverse needs and constraints.

Figure 1. Non-formal adult learning predominates

Note: Adults aged 25-65, formal and non-formal job-related adult learning in the 12 months prior to the survey. OECD, (2024) Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2023) Database,

Today, adult learning is predominantly delivered over a short time period. The latest PIAAC data show that 42% of non-formal training activities last a day or less, and another 40% last no longer than a week. Nearly half of activities, on average, are delivered at least partly on line. These “bite-sized” modules help time-constrained workers access training and represent a pragmatic response to modern work patterns. Yet, their brevity may limit opportunities for deeper skill development. Without stackable credentials or clear pathways between short courses, many adults accumulate learning experiences that do not translate into significant career advancement.

Training duration differs sharply between employed and unemployed adults. Those in work mostly take short, targeted courses that complement their current roles; only about 15% participate in training lasting more than a week. Among unemployed adults, that share rises to almost 40%, reflecting both greater time availability and the broader reskilling often required to re-enter employment.

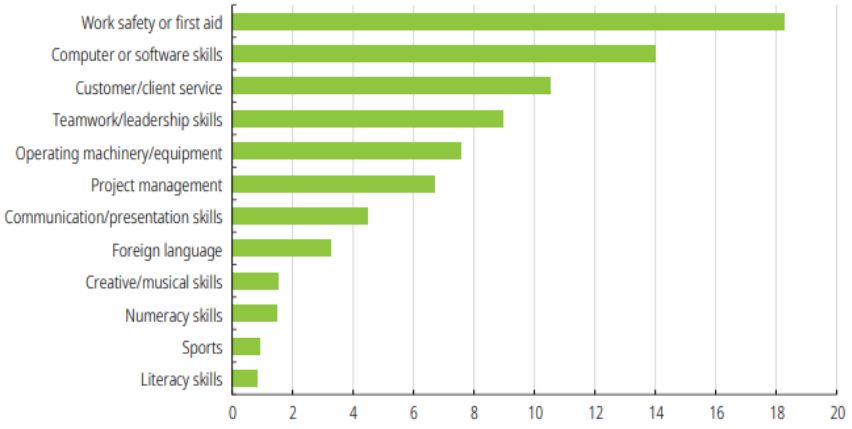

A further challenge lies in what adults are learning. Nearly one-fifth of all job-related non-formal learning across the OECD focuses on health and safety training. While such courses are essential, their predominance suggests that less time is spent on developing the future-oriented skills – digital, green, and managerial – that economies increasingly need. In some countries, compliance training makes up a quarter or more of all job-related learning, crowding out more transformative opportunities for upskilling and reskilling.

Figure 2. Compliance-based training predominates

Note: Adults aged 25-65, non-formal job-related learning. Respondents were asked to identify a single primary focus of the most recent adult learning activity undertaken. OECD, (2024) Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2023) Database,

Opportunities and challenges ahead

The current stagnation is particularly concerning because skills demand is anything but static. Artificial intelligence, automation, and new technologies are transforming the nature of work. The green transition is creating new industries and requiring new skillsets. Population ageing means workers must adapt repeatedly over longer careers. In this context, inaction is costly: if learning does not accelerate, skills gaps will widen, growth will slow, and inequality will deepen.

Despite all this, there are promising signs of innovation. Many countries are experimenting with modular and micro-credential-based learning, which allows adults to acquire skills in smaller, stackable units that can be combined into larger qualifications. Hybrid and online formats are expanding access to people who previously could not fit learning around work or family responsibilities. Examples such as France’s Individual Learning Account (Compte Personnel de Formation) or New Zealand’s Micro-credential Framework show how public policy can empower individuals to invest in their own development.

Flexibility alone is not enough. Short and online courses will only deliver their potential if they are recognised, portable and valued by employers. Otherwise, adult learning risks becoming fragmented – a proliferation of isolated trainings that fail to add up to meaningful progress. Effective lifelong learning systems strike a balance: they make participation easy and flexible, but they also ensure that learning builds cumulatively towards stronger employability and productivity.

Sound policy can bolster participation and quality

Reversing these trends will require a deliberate policy effort to make learning more accessible, relevant, and rewarding. Three priorities stand out:

- Expand access and remove barriers. Training leave policies, flexible scheduling, and targeted financial incentives can help adults – especially those in non-standard jobs or with caring responsibilities – find time to learn.

- Align learning with labour-market needs. Public support and employer partnerships should focus on the skills most in demand, such as digital, green and managerial competencies, to ensure learning leads to real career opportunities.

- Improve recognition and progression. Building coherent frameworks for micro-credentials and stackable learning can turn short courses into cumulative qualifications that are portable across employers and sectors.

The stagnation in adult learning participation is not inevitable. Countries like Ireland and Estonia have shown that steady progress is possible through well-designed incentives and coordinated systems. But change requires political will, sustained investment and strong partnerships between governments, employers and learners.

Lifelong learning must become a core organising principle of labour-market and skills policy. As economies confront digital and green transformations, and as working lives extend, the capacity of adults to continue learning will shape both individual opportunity and national prosperity. The message from the data is clear: unless we reignite participation in adult learning, we risk a future where too many workers – and too many economies – are left behind.

Future articles will explore barriers to participation and inequalities in accessing adult learning opportunities, and lay out a policy agenda to get the most out of adult learning.

By Anja Meierkord (Analyst, OECD), Roland Tusz (Analyst, OECD) and Glenda Quintini (Head of Skills and Future Readiness, OECD)

Responses