STUDENT RETENTION – MOTIVATION MATTERS

Firstly, as a student myself, and then as a lecturer, I have always been interested in motivation: what makes someone tick. My 10 years’ experience as a lecturer gave me an insight into individual and group learner performance, and the reasons behind their results – and it became obvious to me that motivation was a crucial factor – in both directions.

In other words, motivation matters. However, I was concerned that, if this is true, tutors do little individually, and the college does little collectively, to focus on this key factor in any systematic way.

So, I decided I would test my theory, and see if, as a result, I could come up with something that would put motivation clearly into focus.

The hypothesis, that I wanted to test, had two linked assumptions:

- Firstly, that although all teachers and managers would agree that motivation matters – for instant, it has had a big impact on retention and attendance, and hence performance, little was being done formally, collectively or consistently, to create, measure and address it. Though all staff acknowledged its importance and impact, it wasn’t being ‘managed’ in the way other key performance indicators were.

- My second assumption was that the factors that affect a learner’s motivation could be identified under 7 headings, so I wanted to test if this assumption were true.

Factors that I thought affected learner motivation were My Magnificent 7!:

- The interest and challenge of the subjects

- The learner’s performance in those subjects

- The learner’s view of their subject teachers

- Impact of other learners

- Other staff, systems and rules

- Accommodation, facilities, timetable and travel

- Non-college created factors and pressures

The order I’ve listed them in isn’t random; the letters A to G indicate the level of ownership available to the college.

In my view, A, B, and C are directly the responsibility of the staff, especially teachers and curriculum managers.

Letters D, E and F are also largely college responsibilities, including all support staff.

And even though letter G is not directly a college responsibility, it can do much to mitigate some of the effects of items that are covered by this letter.

My research was based on a 6th form college – not my own. I invited a cohort of random students to take part, and once I had explained the purpose, methodology and confidentiality, I made it clear that I wanted honest answers, not ones that they thought I might want to hear.

The questionnaire was based around the 7 categories, and each learner had to indicate their overall level of motivation each week, and the extent to which each of the 7 factors contributed to that motivation. The research was conducted over the first 8 weeks of the Autumn Term.

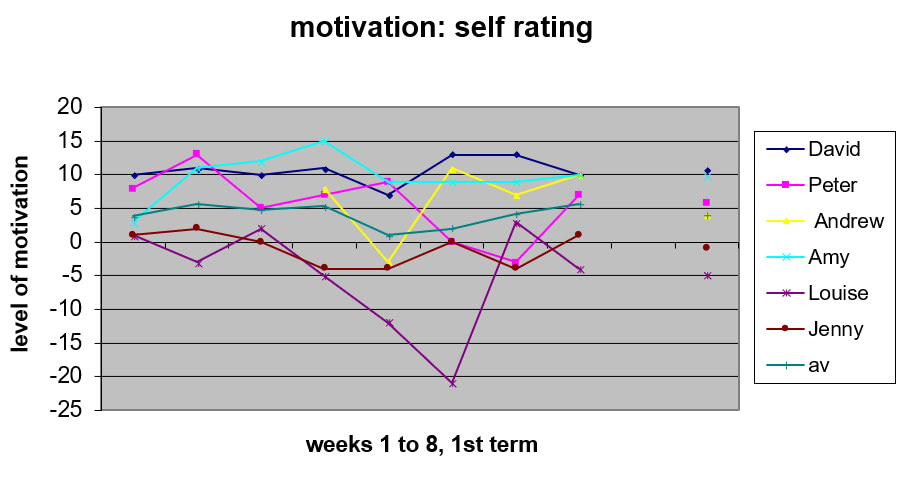

I’ve provided three slides to show some of the results produced. The horizontal axis represents the 8 weeks, and the vertical axis the level of motivation; minus is low, and plus is high. A full interpretation of the results would require more space than this article allows. However, each slide reveals an interesting result.

SLIDE A:

Slide A summarises the result for one cohort of 6 students over the 8 weeks.

Slide A shows how diverse and divergent each of the cohort’s motivation was over that 8-week period. In fact, the average for this cohort mirrors none of the individual results…showing the danger perhaps of taking ‘class averages’ and once again making a case for a differentiated approach to motivation.

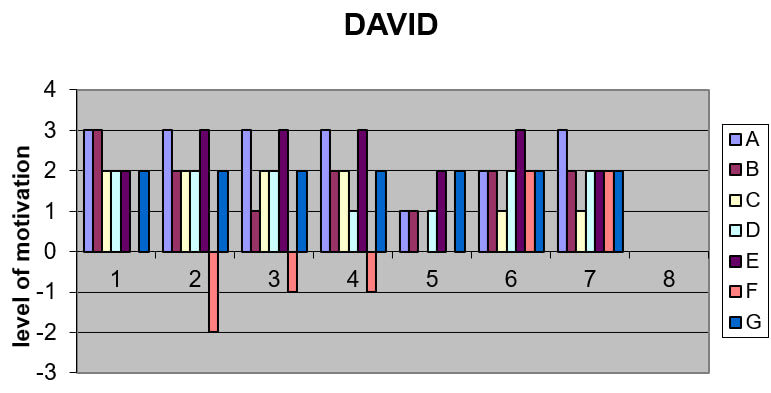

SLIDE B:

Slide B shows the motivational profile for one of that group: David.

Slide B seems to represent a model learner – most of the motivation factors are positive, and significantly so. On closer inspection however, and talking to David about the results, revealed a significant issue that otherwise might have stayed hidden. The F factor covers ‘accommodation, facilities, timetable and travel’.

For David, his demotivation in this factor was based entirely on the lack of secure lockers. As an A-level law student, he had a significant number of books to carry around; he also had a poor back, as a result of a car accident. There were no secure lockers in the college…which almost led to David seeking another college.

So, two key learning points:

- Firstly, would the college have lost David if I hadn’t been tracking his motivation, and talking to him about his concerns?

- Secondly, his very positive scores elsewhere might not have been enough to keep him at that college.

At this point it is perfectly reasonable to conclude that this is what the personal tutor process should cover. The point is…it didn’t. David, who is an extremely confident, able and articulate student, didn’t think to mention it, because “what was the point?

If they could have provided such lockers, they would have, wouldn’t they?” So, given that the personal tutor process did not pick this up, the college may have lost David – and at the point I talked to him, he was actively looking for an alternative college…

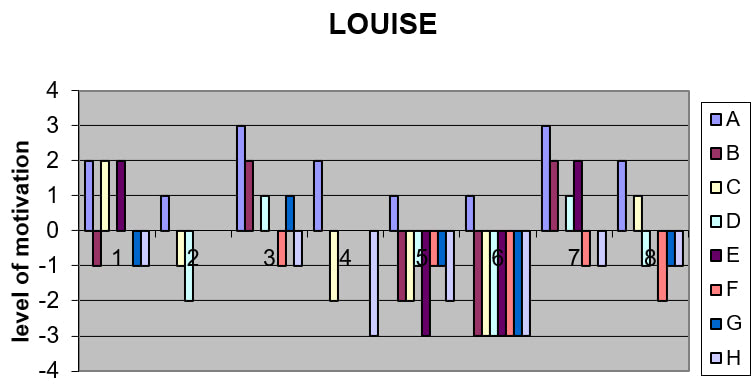

SLIDE C:

Slide C shows the motivational profile for another learner from that cohort: Louise (the names have been changed).

Slide C shows very different profile for another of the cohort, Louise, but again, it contains useful information. Louise was consistently and strongly motivated in what mattered most to her: A, C and E – the subjects, the teachers and the overall college systems.

However, the slide clearly shows a period of crisis around weeks 5 and 6. 6 of the 7 factors score rock bottom in terms of her motivation.

What happened?

The answer lay in a domestic crisis – nothing to do with the college. But Louise found it difficult to concentrate on, and value, anything happening at college because of this crisis – in other words, she lost heart, and the crisis at home completely displaced her motivation for college. It was only her commitment to the subject that kept her attending.

It is understandable that a home crisis will create displacement, but what interested me about the results was that Louise did not simply score the other factors as ‘neutral’. She scored as low as she could.

Taking a look at her profile over the period to that point actually shows Louise (unlike David) never rated those support factors. Her profile suggests (and a conversation later confirmed) she was really in college to study her subjects, which she loved.

She had little connection to the rest of college life, which she didn’t actually value, and often felt was unsupportive. She lived locally, and most of her activity centred around home. So, when the crisis hit, she found the other support factors unhelpful and restrictive – so she almost left, too.

Again, we might hope the personal tutor system would pick all this up – but again, it didn’t (in Louise’s case she said she had had little need and didn’t rate her personal tutor – especially as that need was met through a very supportive family at home….

Even from this small sample, it shows to me that it might be helpful (and certainly possible, in technology terms) to add such a process to the existing tracking system, which tends to focus on easily measurable and testable results, such as grades, attendance and punctuality, and be missing the softer side of achievement, which is where motivation would sit.

Arnie Skelton, Managing Director, Effective Training & Development Ltd

Copyright © 2018 FE News

The survey is very limited, but useful as a pilot; if anyone reading this is interested in doing something similar within their college, I’d love to extend the research, so please get in touch – [email protected].

Responses