Dear Diary, Today I Learned About Reflective Practice….

‘Reflection’, What Exactly Is It?

Whilst I was in the middle of writing this article, I turned on the news to hear the latest Corona-update from Boris and the gang.

Professor Chris Whitty was mumbling a response to a typically tricky Peston question: “...learn lessons as we go along….learning lessons after you’ve gone through something is absolutely critical..”

Lots of lessons to be learnt then, but what he was actually highlighting was the power of reflective learning; it’s all around us and something I’m going to talk about right now.

Most people would be able to have a good go at defining ‘reflection’. I asked family and friends to try and most answers included ‘mirror’, ‘looking at yourself’ etc. Sort of on the right lines. Out of the widely accepted definitions, I like Linda Finlay’s (from Reflecting on Reflective Practice, 2008): “…recapture practical experiences and mull them over critically in order to gain new understandings and so improve future practice.” Success or failure, mull it over….improve…this resonates with me.

Yes, but success is easy to deal with, however, failure, well that’s another matter; it can lead to loss of confidence and negativity. Reflection is a very important skill and can counterbalance failing by helping you to learn from mistakes, to build up the experience bank and, through this, turn failure into a positive. It’s okay to fail, J.K. Rowlings swears by it; she was rejected twelve times by different publishers and each time she went away to lick her wounds, she took on board the feedback to improve her offering until she was finally accepted by Bloomsbury….the rest is history.

Reflection as a specialised form of thinking

The concept of reflection has been around since time immemorial, but the ideas are articulated through the formal subject of Reflective Practice, which is the theory and application of “how to reflect”.

There has been a lot of research carried out on this subject and its application to professions, notably in nursing, teaching, sport and, as Chris Witty would confirm, science.

The father of RP was John Dewey; he carried out studies in the 1930s and famously said “We don’t learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.”

Think about it.

A solicitor might do the first in the office, whereas a barrister the latter in court. Both require knowledge and experience. In the quote above, Chris Whitty was talking about both of these types of reflecting.

To get meaning from experiences requires reflection and these dual concepts have resulted in the development of the process of analysing the present or past, evaluating and then looking to improve, which has, in turn, led to the reflective cycle models I’m coming on to.

| Another big player in the development of reflective practices was Donald Schon, who, in 1983, proposed the ideas of: | ||

| Reflection-ON-Action | This is analysing past practice AFTER the event to consider improvements, a ‘cognitive post-mortem’ so to speak to assess what worked well, and what could have been done better. |

| Reflection-IN-Action | Thinking about issues DURING the activity, known as ‘thinking on your feet’ or professional artistry. This is using a combination of knowledge and experience to solve a problem. | |

Reflective Models

First Kolb’s Experiential Learning Styles

The earliest Reflective Model was developed by David Kolb, who published his Kolb’s Experiential Learning Styles in 1984.

His theory proposed that effective learning is achieved when a person progresses through a cycle of four stages, the second stage being that of reflective observation.

| David Kolb’s learning cycle basically involves four stages: |

| Concrete learning Reflective observation Abstract conceptualization, and Active experimentation |

This means taking time-out from “doing”, stepping back from the task and reviewing what has been done and experienced.

Then Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle

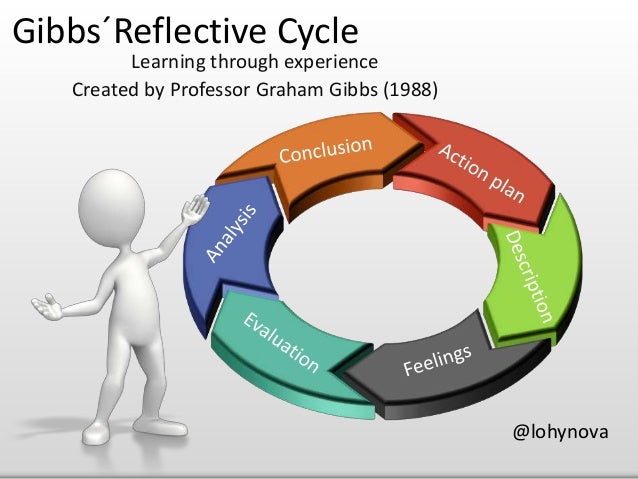

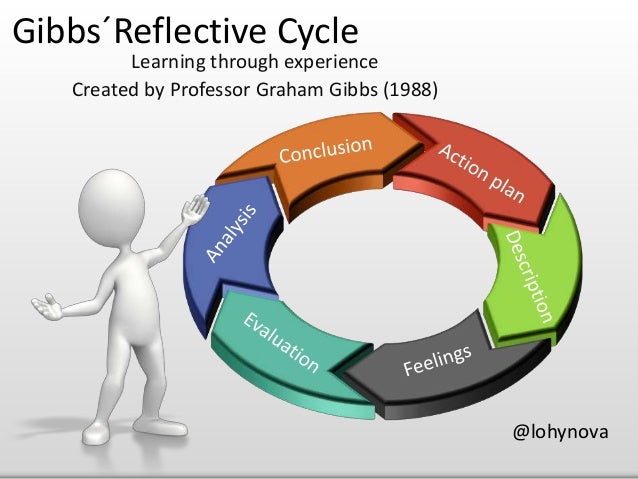

Subsequent to Kolb, and inspired by him, the American sociologist and psychologist Graham Gibbs published his Reflective Cycle model in his book ‘Learning by Doing‘ in 1988.

‘It is not sufficient simply to have an experience in order to learn. Without reflecting upon this experience, it may quickly be forgotten, or its learning potential lost. It is from the feelings and thoughts emerging from this reflection that generalisations or concepts can be generated and it is generalisations that allow new situations to be tackled effectively.’ Learn from experience is Gibbs’ message, which is easier if you’ve been doing ‘it’ for a while.

This model is widely used in practice to help structure or scaffold the reflection process. It encourages systematic thinking about experiences during an activity or situation with the intention of making people more aware and be able to change behaviour.

It is the platform for instilling the habit of Lifelong Learning. There are more sophisticated and complex models which offer more detailed questioning, but this is a good place to start, especially for people with little experience.

Gibbs’ cycle is a loop which consists of six stages which invoke answers to questions:

| Description | This stage is about pulling together the facts of the event. No judgements yet. There can be a number of questions to act as prompts, such as: What happened? Where? Who? When? What were people’s reactions? |

| Feelings | Consider the emotions which were experienced through the event. Before? During? After? |

| Evaluation | Evaluate the situation to consider what went well, what went worse than expected? Positives and negatives? Here you can add theories. |

| Analysis | Consideration of what helped or hindered the situation. |

| Conclusion | Consider what was learned from the situation. What else could you have done? What skills would help next time? How differently would you react? |

| Action Plan | This area deals with the plan of how to effectively improve the situation next time. Any training, skill, or habit that can equip you with handling the situation better if it occurs again? |

Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle gives a framework and some prompts, which makes it usable with novices. This is the model we adhere to at Kloodle to help students reflect on projects or work experience.

Chronicles Through History

History is packed full of many diverse examples of committed individuals using journals. From Claudius, whose diaries preserve the day-to-day minutiae to help us piece together the political strands of Roman life, to Jackie Charlton, the legendary England centre-half from ’66, who kept a ‘little black book’ containing the details of which centre-forwards he had to exact revenge on.

One more recent and topical chronicling example is Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook. The tech genius used to sketch out his hand-written ideas and mission, supported by diagrams and flowcharts, on unlined pages in notebooks.

These musings were the seedlings of his business plans over the next decade. Visitors to his minimalist apartment in Palo Alto remarked that the pile of journals in his living room stood out as the focal point and this signified the importance.

Over the years he would revisit the ideas to check his rationale and what had changed.

It wasn’t all plain sailing; as Zuckerberg said: “We have certainly made a bunch of mistakes. If you’re not making mistakes, you’re not living up to your potential, right? That’s how you grow.” And that’s what they did. Steven Levy has written a book about the remaining notebooks in ‘The Inside Story’.

Getting Into The Habit When You’re Young

Reflection is not a natural skill for young people. At school there is very little time built into the curriculum for this reflection stuff, so young people tend to find it unnatural. It is not something they are taught to do from an early age.

Instead, the focus in education is on being consumers rather than producers of knowledge; passive listening to the teacher, rote learning to ‘fill in the blanks’, give the answer the examiner wants or just answer C to multiple choice questions. This becomes routine.

However, a process of being able to construct meaning from information and then apply the knowledge is very good preparation for further education and the world of work. It is important to think and learn independently, not just doing it for the sake of pleasing the teacher.

To make crucial decisions, you need a cognitive process to turn feelings and thoughts into clear actions. You must be encouraged to have a go, change things, to get things wrong and then do something about it.

A recent working paper by Gino and Pisano of Harvard Business School provides clear evidence that reflecting on what you’ve done teaches you to do it better next time. Common sense, right?

Novices, in particular, need time to step back and think through a situation, otherwise they become “trapped in unexamined judgements” (Finlay).

Challenging the status quo, the current methodology, leads to critical analysis and on to the development of new perspectives. This might be uncomfortable, especially if it contradicts what the teacher has told you to do!

How To Do It In Practice

Ideally, reflection shouldn’t be prescriptive, a mechanical tick-box exercise, because the purpose is to challenge concepts and ideas. Having said that, according to Finlay: “The problem with reflective practice is that it is hard to do and equally hard to teach. It is even harder to do and teach effectively.”

There are many different ways to reflect and much of it is subjective. It is important that students see that in real-life there is uncertainty and no clear-cut answers, which is at odds with the traditional fact-based class approach.

So, it is important to give students some structure to develop their own style of effective reflection.

Research shows that for reflective practice to be successful it should be continuous, so it becomes a habit, not just for a one-off project. It needs to link course content and the work experience explicitly, and, also, it should be challenging, forcing students to confront their own assumptions and tackle hard questions. One of the most powerful activities of reflection to deepen understanding is the use of learning logs and diaries.

The reflective diary is a key tool to facilitate reflective learning. Writing journals requires students to reflect on the teaching and learning activities and provides an opportunity to search for and express their learning in a personal way, to relate and apply their learning to their own assessment circumstance.

Reflection In Sport And Education

HUDL

Reflective practice is common practice in many disciplines where failure is likely and learning from failure is important to rectify. Two which spring to mind are sport and education. In sport, one example is England Hockey who use a system called Hudl.

The players will be located all around the country but can access the system remotely. The coach uploads clips from matches and training and asks the squad members to analyse and comment privately or in plenum.

This works well at junior level where an immediate post-mortem of a defeat may hammer home the negativity and fear of failure can inhibit performance. Whereas a discussion few weeks on can result in better acceptance and preparation.

EPQ

A great example of the use of reflection in education is the EPQ (Extended Project Qualification) at AS level.

Both of my kids have done it and it’s grown up stuff. The student presents a topic for investigation and devises an appropriate research question, usually answered by an extended essay of around 5,000 words, which is supported by a presentation. This requires a high degree of planning with self-motivated, autonomous work.

A growing number of universities value this type of research-based qualification where students demonstrate many skills which will be useful at university and on to the workplace. The project must be ‘reflective’ and in fact it was introduced to bridge the gap between the rote learning for formal exams and uni.

One of the key aspects of the EPQ is that candidates have to provide evidence that they have spent time reflecting on their work and the way they do this is by using a log-book; making changes to the original plans, or not, dependent on those reflections.

Candidates are encouraged to go down the wrong route, rip up and start again; a bit like real life! Also, to reinforce this, final marks are actually allocated to reflection. This type of process does not come naturally to young people who have never been taught how to do it. Some learners instinctively create highly-reflective journals, but many struggle and find it a hassle.

The teacher is a key ingredient in making this activity a success; they act as a mentor and push students to think clearly about what they are doing by asking questions, helping them make connections and providing feedback.

Concluding Reflections

In summary, being able to reflect effectively is a major component of emotional intelligence and a very important skill for university, work and life.

It can be a habit which is a major pillar of lifelong learning and the earlier you start then the more useful it is likely to prove as you adapt your own style.

A prop for reflection is the journal; a diary logging your thoughts and rationale, to which you can refer back in order to check understanding and which mistakes to avoid in future………. Chris Whitty is probably doing that right now!

Neil Wolstenholme, Chairman, Kloodle

The first article in this series was “T Levelling Up: The “Levelling Up” Agenda Must Result In Equality With A Levels“

In the third of our trilogy of articles, we shall explore how all of this forms the bedrock for Kloodle’s digital support for students doing T levels.

‘Reflection’, What Exactly Is It?

Whilst I was in the middle of writing this article, I turned on the news to hear the latest Corona-update from Boris and the gang.

Professor Chris Whitty was mumbling a response to a typically tricky Peston question: “...learn lessons as we go along….learning lessons after you’ve gone through something is absolutely critical..”

Lots of lessons to be learnt then, but what he was actually highlighting was the power of reflective learning; it’s all around us and something I’m going to talk about right now.

Most people would be able to have a good go at defining ‘reflection’. I asked family and friends to try and most answers included ‘mirror’, ‘looking at yourself’ etc. Sort of on the right lines. Out of the widely accepted definitions, I like Linda Finlay’s (from Reflecting on Reflective Practice, 2008): “…recapture practical experiences and mull them over critically in order to gain new understandings and so improve future practice.” Success or failure, mull it over….improve…this resonates with me.

Yes, but success is easy to deal with, however, failure, well that’s another matter; it can lead to loss of confidence and negativity. Reflection is a very important skill and can counterbalance failing by helping you to learn from mistakes, to build up the experience bank and, through this, turn failure into a positive. It’s okay to fail, J.K. Rowlings swears by it; she was rejected twelve times by different publishers and each time she went away to lick her wounds, she took on board the feedback to improve her offering until she was finally accepted by Bloomsbury….the rest is history.

Reflection as a specialised form of thinking

The concept of reflection has been around since time immemorial, but the ideas are articulated through the formal subject of Reflective Practice, which is the theory and application of “how to reflect”.

There has been a lot of research carried out on this subject and its application to professions, notably in nursing, teaching, sport and, as Chris Witty would confirm, science.

The father of RP was John Dewey; he carried out studies in the 1930s and famously said “We don’t learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.”

Think about it.

A solicitor might do the first in the office, whereas a barrister the latter in court. Both require knowledge and experience. In the quote above, Chris Whitty was talking about both of these types of reflecting.

To get meaning from experiences requires reflection and these dual concepts have resulted in the development of the process of analysing the present or past, evaluating and then looking to improve, which has, in turn, led to the reflective cycle models I’m coming on to.

| Another big player in the development of reflective practices was Donald Schon, who, in 1983, proposed the ideas of: | ||

|

Reflection-ON-Action | This is analysing past practice AFTER the event to consider improvements, a ‘cognitive post-mortem’ so to speak to assess what worked well, and what could have been done better. |

| Reflection-IN-Action | Thinking about issues DURING the activity, known as ‘thinking on your feet’ or professional artistry. This is using a combination of knowledge and experience to solve a problem. | |

Reflective Models

First Kolb’s Experiential Learning Styles

The earliest Reflective Model was developed by David Kolb, who published his Kolb’s Experiential Learning Styles in 1984.

His theory proposed that effective learning is achieved when a person progresses through a cycle of four stages, the second stage being that of reflective observation.

| David Kolb’s learning cycle basically involves four stages: |

|

This means taking time-out from “doing”, stepping back from the task and reviewing what has been done and experienced.

Then Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle

Subsequent to Kolb, and inspired by him, the American sociologist and psychologist Graham Gibbs published his Reflective Cycle model in his book ‘Learning by Doing‘ in 1988.

‘It is not sufficient simply to have an experience in order to learn. Without reflecting upon this experience, it may quickly be forgotten, or its learning  potential lost. It is from the feelings and thoughts emerging from this reflection that generalisations or concepts can be generated and it is generalisations that allow new situations to be tackled effectively.’ Learn from experience is Gibbs’ message, which is easier if you’ve been doing ‘it’ for a while.

potential lost. It is from the feelings and thoughts emerging from this reflection that generalisations or concepts can be generated and it is generalisations that allow new situations to be tackled effectively.’ Learn from experience is Gibbs’ message, which is easier if you’ve been doing ‘it’ for a while.

This model is widely used in practice to help structure or scaffold the reflection process. It encourages systematic thinking about experiences during an activity or situation with the intention of making people more aware and be able to change behaviour.

It is the platform for instilling the habit of Lifelong Learning. There are more sophisticated and complex models which offer more detailed questioning, but this is a good place to start, especially for people with little experience.

Gibbs’ cycle is a loop which consists of six stages which invoke answers to questions:

| Description | This stage is about pulling together the facts of the event. No judgements yet. There can be a number of questions to act as prompts, such as: What happened? Where? Who? When? What were people’s reactions? |

| Feelings | Consider the emotions which were experienced through the event. Before? During? After? |

| Evaluation | Evaluate the situation to consider what went well, what went worse than expected? Positives and negatives? Here you can add theories. |

| Analysis | Consideration of what helped or hindered the situation. |

| Conclusion | Consider what was learned from the situation. What else could you have done? What skills would help next time? How differently would you react? |

| Action Plan | This area deals with the plan of how to effectively improve the situation next time. Any training, skill, or habit that can equip you with handling the situation better if it occurs again? |

Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle gives a framework and some prompts, which makes it usable with novices. This is the model we adhere to at Kloodle to help students reflect on projects or work experience.

Chronicles Through History

History is packed full of many diverse examples of committed individuals using journals. From Claudius, whose diaries preserve the day-to-day minutiae to help us piece together the political strands of Roman life, to Jackie Charlton, the legendary England centre-half from ’66, who kept a ‘little black book’ containing the details of which centre-forwards he had to exact revenge on.

One more recent and topical chronicling example is Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook. The tech genius used to sketch out his hand-written ideas and mission, supported by diagrams and flowcharts, on unlined pages in notebooks.

These musings were the seedlings of his business plans over the next decade. Visitors to his minimalist apartment in Palo Alto remarked that the pile of journals in his living room stood out as the focal point and this signified the importance.

Over the years he would revisit the ideas to check his rationale and what had changed.

It wasn’t all plain sailing; as Zuckerberg said: “We have certainly made a bunch of mistakes. If you’re not making mistakes, you’re not living up to your potential, right? That’s how you grow.” And that’s what they did. Steven Levy has written a book about the remaining notebooks in ‘The Inside Story’.

Getting Into The Habit When You’re Young

Reflection is not a natural skill for young people. At school there is very little time built into the curriculum for this reflection stuff, so young people tend to find it unnatural. It is not something they are taught to do from an early age.

Instead, the focus in education is on being consumers rather than producers of knowledge; passive listening to the teacher, rote learning to ‘fill in the blanks’, give the answer the examiner wants or just answer C to multiple choice questions. This becomes routine.

However, a process of being able to construct meaning from information and then apply the knowledge is very good preparation for further education and the world of work. It is important to think and learn independently, not just doing it for the sake of pleasing the teacher.

To make crucial decisions, you need a cognitive process to turn feelings and thoughts into clear actions. You must be encouraged to have a go, change things, to get things wrong and then do something about it.

A recent working paper by Gino and Pisano of Harvard Business School provides clear evidence that reflecting on what you’ve done teaches you to do it better next time. Common sense, right?

Novices, in particular, need time to step back and think through a situation, otherwise they become “trapped in unexamined judgements” (Finlay).

Challenging the status quo, the current methodology, leads to critical analysis and on to the development of new perspectives. This might be uncomfortable, especially if it contradicts what the teacher has told you to do!

How To Do It In Practice

Ideally, reflection shouldn’t be prescriptive, a mechanical tick-box exercise, because the purpose is to challenge concepts and ideas. Having said that, according to Finlay: “The problem with reflective practice is that it is hard to do and equally hard to teach. It is even harder to do and teach effectively.”

There are many different ways to reflect and much of it is subjective. It is important that students see that in real-life there is uncertainty and no clear-cut answers, which is at odds with the traditional fact-based class approach.

So, it is important to give students some structure to develop their own style of effective reflection.

Research shows that for reflective practice to be successful it should be continuous, so it becomes a habit, not just for a one-off project. It needs to link course content and the work experience explicitly, and, also, it should be challenging, forcing students to confront their own assumptions and tackle hard questions. One of the most powerful activities of reflection to deepen understanding is the use of learning logs and diaries.

The reflective diary is a key tool to facilitate reflective learning. Writing journals requires students to reflect on the teaching and learning activities and provides an opportunity to search for and express their learning in a personal way, to relate and apply their learning to their own assessment circumstance.

The reflective diary is a key tool to facilitate reflective learning. Writing journals requires students to reflect on the teaching and learning activities and provides an opportunity to search for and express their learning in a personal way, to relate and apply their learning to their own assessment circumstance.

Reflection In Sport And Education

HUDL

Reflective practice is common practice in many disciplines where failure is likely and learning from failure is important to rectify. Two which spring to mind are sport and education. In sport, one example is England Hockey who use a system called Hudl.

The players will be located all around the country but can access the system remotely. The coach uploads clips from matches and training and asks the squad members to analyse and comment privately or in plenum.

This works well at junior level where an immediate post-mortem of a defeat may hammer home the negativity and fear of failure can inhibit performance. Whereas a discussion few weeks on can result in better acceptance and preparation.

EPQ

A great example of the use of reflection in education is the EPQ (Extended Project Qualification) at AS level.

Both of my kids have done it and it’s grown up stuff. The student presents a topic for investigation and devises an appropriate research question, usually answered by an extended essay of around 5,000 words, which is supported by a presentation. This requires a high degree of planning with self-motivated, autonomous work.

A growing number of universities value this type of research-based qualification where students demonstrate many skills which will be useful at university and on to the workplace. The project must be ‘reflective’ and in fact it was introduced to bridge the gap between the rote learning for formal exams and uni.

One of the key aspects of the EPQ is that candidates have to provide evidence that they have spent time reflecting on their work and the way they do this is by using a log-book; making changes to the original plans, or not, dependent on those reflections.

Candidates are encouraged to go down the wrong route, rip up and start again; a bit like real life! Also, to reinforce this, final marks are actually allocated to reflection. This type of process does not come naturally to young people who have never been taught how to do it. Some learners instinctively create highly-reflective journals, but many struggle and find it a hassle.

The teacher is a key ingredient in making this activity a success; they act as a mentor and push students to think clearly about what they are doing by asking questions, helping them make connections and providing feedback.

Concluding Reflections

In summary, being able to reflect effectively is a major component of emotional intelligence and a very important skill for university, work and life.

It can be a habit which is a major pillar of lifelong learning and the earlier you start then the more useful it is likely to prove as you adapt your own style.

A prop for reflection is the journal; a diary logging your thoughts and rationale, to which you can refer back in order to check understanding and which mistakes to avoid in future………. Chris Whitty is probably doing that right now!

Neil Wolstenholme, Chairman, Kloodle

The first article in this series was “T Levelling Up: The “Levelling Up” Agenda Must Result In Equality With A Levels“

In the third of our trilogy of articles, we shall explore how all of this forms the bedrock for Kloodle’s digital support for students doing T levels.

Responses