Learning Factories: On the route to science Superpowerdom?

This week the Gatsby Foundation has published The Opportunity for Learning Factories in the UK, the report I have been working on for them over the past nine months.

I am going to try to explain here what that opportunity is, why it is relevant now, and how it can be grasped.

Boris Johnson’s New Year message spoke of 2021 being the year when we bounce back from COVID and can “turbo-charge” the ambition for post-Brexit UK to be a “science superpower” creating “millions of high skilled jobs”.

Boris Johnson’s New Year message spoke of 2021 being the year when we bounce back from COVID and can “turbo-charge” the ambition for post-Brexit UK to be a “science superpower” creating “millions of high skilled jobs”.

He reassured us that we could now see “exactly how we are going to get there” with the new vaccines to fightback against COVID.

As yet, it remains somewhat less clear how we are going to become a science superpower capable of creating millions of high skilled jobs.

So what have ‘learning factories’ got to do with any of this?

I wrote a piece for FE News back in the summer – ‘Learning Factories’: What they are and why their time has come – to introduce the concept, which is not widely understood or recognised in the UK.

To recap briefly, a learning factory has nothing to do with rote learning, but is an authentic simulated working environment designed to facilitate experiential learning, practical projects and collaborative problem solving.

Imagine an industrial adventure playground rather than a classroom. And one that can link together research and innovation with education and training.

My report argues that facilities of this type could play a more significant role in translating scientific excellence into jobs and prosperity. This will need some strategic encouragement and co-ordination, but now is the moment to grasp the opportunity.

The pace of change of industrial digitalisation is accelerating. UK manufacturing industry has to take advantage of new technologies to be competitive in a post COVID, post Brexit world. And that will only be possible at scale if two closely linked and long standing issues are addressed: diffusion and adoption of innovation, and higher level technical skills.

Hub No Spokes

Currently the skills and innovation systems in the UK do not work together as effectively as they should. The UK has world leading science, and companies that are highly innovative and at the cutting edge of new technologies, but the benefits are not shared by the wider economy. Manufacturers in particular often struggle to access the skilled workforce they need to turn such innovation into profit and maintain their competitiveness taking advantage of latest technologies.

In a speech delivered in 2018 entitled The UK’s Productivity Problem: Hub No Spokes , Andrew Haldane, the Chief Economist at the Bank of England, highlighted the UK’s long and growing tail of firms in which productivity growth has effectively stalled as a key factor accounting for the UK’s inferior productivity as a national economy. The UK is very strong at top-end innovation, but has fewer institutional spokes supporting technological trickle down.

The formation of the Catapult network since 2011 is seen as a positive by Haldane, strengthening the presence of centres of innovation in key sectors.

However, he also observes that compared to the Fraunhofer network in Germany on which the Catapults are modelled, the UK network is still much smaller and more limited in scope, serving “more as an innovation than a diffusion engine, leaving largely untouched the long tail of UK companies”.

Technicians and Innovation

A major part of the diffusion problem is a skills and human capital deficit. The UK’s comparative weakness in technical education, especially at level 3/4/5 technician skills, has been widely recognised.

The Report of the Independent Panel on Technical Education chaired by David Sainsbury in 2016 highlighted the issue and it was a major focus of the Government’s subsequent Post-16 Skills Plan, and this was reiterated in last week’s Skills for Jobs White Paper.

The reason this matters in an innovation context is the contribution that technicians make not just to the innovation process itself but to the absorptive capacity of firms and their ability to apply new technologies.

This was emphasised in a report on Technicians and Innovation commissioned by Gatsby in 2019 from Professor Paul Lewis of King’s College.

Considering the UK’s provision of technical education from an innovation systems perspective, the report identifies a systemic failure whereby employers struggle to find up to date practical training for technician apprentices to learn how to use new methods of production associated with emerging technologies, and local colleges and training providers have little incentive to provide what they need.

Learning Factories in a Skills Value Chain

The UK Catapult network is now recognising that to fulfil its role in diffusing innovation more effectively it needs to find new ways to engage with the skills system and bridge the current disconnect.

The main focus of the Manufacturing the Future Workforce Report published by the High Value Manufacturing Catapult in 2020 was on how best to do this, reflecting on lessons drawn from a series of study visits to Germany, Ireland, Switzerland, Singapore and the USA, supported again by Gatsby.

The report’s overarching recommendation is to use the concept of a ‘skills value chain’ as an organising principle to make improved connections between innovation, education and training initiatives.

Based on observations of international good practice, learning factory type facilities are seen to have the potential to help join up the skills value chain, acting as a physical or virtual manifestation of the links, and it is recommended that they should be promoted as an education model to enable industrial digitalisation.

My report follows up on that recommendation and analyses in more detail the potential contribution that learning factories could make in the UK and the foundations that could be built on.

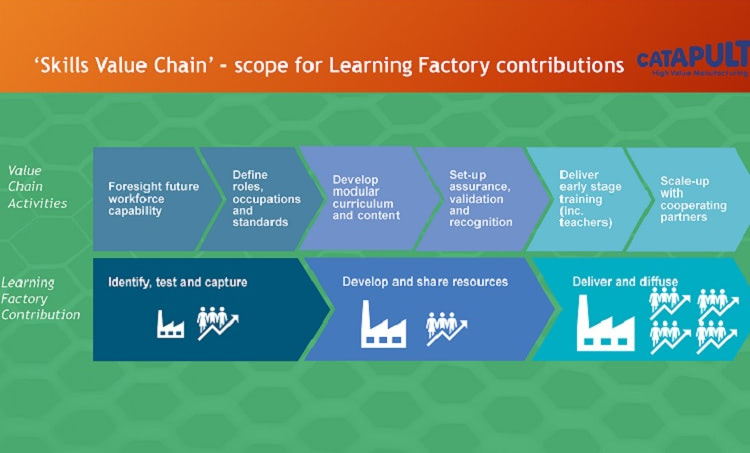

Figure 1 below sets out in schematic form the links in the skills value chain.

This starts on the left with foresighting the future workforce capability needed for the adoption of new and emerging technologies, and runs across to righthand side with scaling up delivery of the skills training needed to create these capabilities.

The second row shows a role for learning factories to contribute and make links across all stages of the skills value chain, though the biggest contribution is likely to be at the righthand end where the delivery of training starts and capacity building is required across the wider skills system to achieve scale and accessibility. My report explains and illustrates these potential contributions at each stage.

Learning Factories in the UK

In terms of current deployment of learning factories, the UK appears to be behind many of its international competitors, but perhaps not as far behind as might be thought at first sight.

The term ‘learning factory’ may rarely be used, but there are developments that have evolved over the years that have many of the features of learning factories, and in the past five years there has been an acceleration of interest and activity reflecting global trends associated with digitalisation and ‘Industry 4.0’.

My report gives a range of examples, including other forms of complex simulated workplace environments that are used for learning purposes in sectors beyond manufacturing.

I have also been able to include five more fully illustrated case studies and some practical guidance based on international research for those who might be considering whether to embark on a learning factory type development.

5 Case Studies of Learning Factory Facilities |

|

The scope for learning factories to make a bigger contribution needs to be seen in a systems context. It is not just about encouraging more facilities to be built and equipped; a more co-ordinated, collaborative approach is also needed to maximise the contribution of existing assets, avoid waste and duplication, and focus on where gaps most need to be filled, whether nationally or locally.

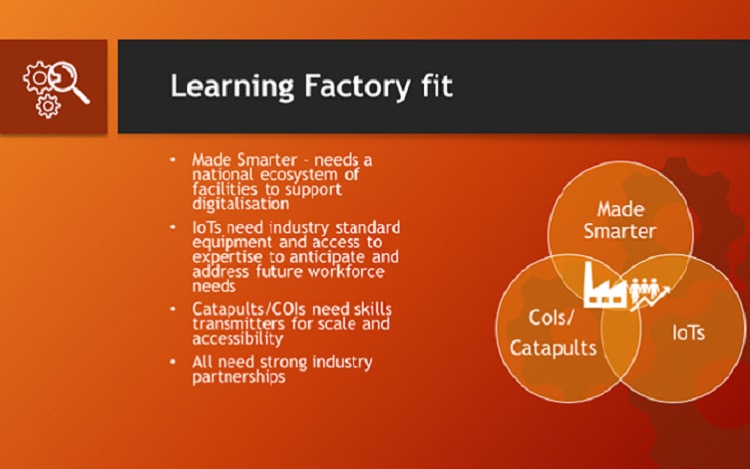

My report proposes, as summarised in Figure 2 below, how three existing foundations can be built on:

- Catapults and other Centres of Innovation (COIs),

- Institutes of Technology (IoTs) and similar centres of skills expertise, and

-

Made Smarter, the industry-led movement on industrial digitalisation.

Catapults, IoTs and Made Smarter

Catapults and COIs could play three main roles within their fields of specialist expertise:

- Identify where there is need for learning factories and similar complex simulated workplace environments, using their understanding of future capability and competency requirements;

- Develop and extend the reach of their own such facilities for skills development and innovation adoption;

- Use their expertise to support the development and operation of learning factories elsewhere, working in partnership with centres of skills expertise, including the emerging network of IoTs.

The remit of Institutes of Technology and the expectations now being set for them fit well with the concept of learning factories. Department for Education guidance emphasises the importance of industry standard facilities and simulated workplace environments, and working with university, innovation centre and employer partners to access their applied research base and prepare the workforce for changes in technology.

Many of the Wave 1 IoTs currently establishing themselves are already developing or incorporating learning factory type facilities within a variety of delivery models which include co-ordinated regional approaches. A national network of IoTs with learning factory capabilities has the potential to be a critical link in creating a more coherent skills value chain, joining up innovation with the skills development needed for adoption at scale, particularly the technician skills needed at levels 4 and 5. Although there is no direct equivalent of the IoT programme in the Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, there are other foundations that could be built on in terms of centres of skills expertise, college networks with a relatively coherent regional geographic focus and a more established college role in supporting businesses with innovation adoption.

Made Smarter’s ambition is to create a digital ecosystem to accelerate the innovation and diffusion of industrial digital technologies, and to upskill industrial workers to enable digital technologies to be successfully exploited. Looking at international practice, learning factory facilities could play a significant part in the national digital ecosystem envisaged by Made Smarter. This includes learning factories being incorporated within digital innovation hubs, acting as demonstrators and technology trialling facilities for adoption programmes, and enabling the delivery of upskilling in digital technologies. This would not necessarily require wholesale new investment in facilities, as much could be achieved by utilising and enhancing the range of services offered through facilities that already exist or are planned through the Catapult and IoT networks and such like.

Co-ordinated support to create the “spokes”

What is required is more co-ordinated support, both at a national government level and in a regional and local economic context.

The Skills for Jobs White Paper includes some encouraging pointers:

- Explicit recognition of the ‘skills value chain concept’

- Local Skills and Improvement Plans

- College Business Centres, and

- The commitment to expand the Institutes of Technology programme.

Additionally my report recommends:

- a systematic mapping exercise of existing and planned learning factory facilities across the UK to inform planning and investment at both national and regional levels, as well as more networking and sharing of expertise

- more attention to building the specialist staff expertise needed to operate learning factory facilities and maximise return on capital investment made

- a co-ordinated approach to developing and sharing specialised learning resources across learning factory networks, including reviewing any common technical standards required

- a concerted effort to use digital technologies such as simulations and digital twins to extend the reach of what can be done through physical learning factory facilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has thrown into relief both the need and opportunity to think differently about how skills challenges are addressed.

The case made by this report is for one element of reform to be the more widespread and systematic adoption of a learning factory approach, creating the ‘spokes’ needed for world leading scientific excellence to translate more readily into high quality jobs. As with vaccines, research and development is vital, but the benefits only come if there are mechanisms to deploy at scale.

Dr Stuart Edwards, independent consultant and adviser, college chair, and honorary research associate at the UCL Knowledge Lab

Dr Edwards was formerly a senior official that the Departments for Education and for Business Innovation and Skills. This study of Learning Factories has been commissioned by the Gatsby Foundation, working with the High Value Manufacturing Catapult.

Responses