Well that escalated quickly! Colleges and Combating the Rise of #FakeNews

‘Lies, damned lies and statistics’ is the well known phrase associated with a dubious argument often using manipulated data to present a contention lacking credibility. A modern equivalent might be ‘lies, alternative facts and fake news’.

Fake news combines two interests for me that are relevant to education, namely people and technology. Whilst it may be popular to focus on technology when discussing fake news, the cause is most definitely people.

It’s people who like or share a particular fake news story and it is our personal education, digital skills, awareness and behavioural characteristics that define our likelihood of being exploited by fake news.

I was thinking about this recently when I observed a story circulating widely on social media relating to a bacon sandwich. No, really. It consisted of an image of a bacon sandwich with the sensational, and not intentionally funny, headline that the image was being removed as it was stated to be offending people.

This was accompanied by an associated demand to share it far and wide by way of angry protest which subsequently happened despite its seemingly obvious absurdity.

To the digitally literate among us, this may appear mind boggling but it’s a perfect example of the criticality of education in solving real world problems.

This somewhat silly example of fake news made me reflect on how and why this is happening and I believe it presents an opportunity for those in FE to address a major national problem receiving high level political attention.

In doing so FE can also make the associated business case for funding to tackle it. Whilst Further Education is facing multiple and complex challenges the future of the sector will be determined by its ability to redefine its role in the world around it.

Combating fake news is a prime example of where FE is uniquely placed to make a difference and to make a case for support.

Anyone working within UK education in recent years will have an awareness of and likely formal training in British Values, the Prevent programme and wider initiatives of noble intention.

Alongside the huge national investment in all of this there has been an epidemic of fake news that threatens to undermine the objectives of these initiatives. Just as with growing a particular plant, to cultivate fake news specific conditions have to be present for it to thrive and grow and education plays a key role in this.

A number of years ago I developed an online digital literacy course that included, among other things, a focus on online etiquette as well as how to stay safe online.

The same principles underpinning that course formed the key themes of a policy I developed years later called ‘Digital Professionalism’ that provided a clear framework and support mechanism for staff and students to thrive and stay safe in digital spaces.

Both of these initiatives were long before what we now call fake news but they are directly relevant to the issues that education is tackling as people escalate issues and behave in a way online they would often be unlikely to in person.

This matters because digital behaviour can have physical consequences. It’s not hard to find colleagues in education who have direct experience of dealing with issues that have arisen outside of the physical classroom in online social media spaces.

As always with education, our attention needs to focus on people, not technology.

To blame a particular technology platform for fake news, or radicalisation, is too simplistic, easy and it won’t help. A social technology platform in itself is benign and no different to a piece of paper.

Fake news is often just the modern equivalent to what in the past would have been called hate mail, but few would rationally argue that paper was the problem back then.

Politicians rounding up digital media executives to grill them over fake news is about as appropriate and effective as if they had rounded up the paper manufacturers of the past to grill them over hate mail.

We are still in the dawn of the fake news era so obtaining academically robust data and evidence on the overall scale and impact of the problem is challenging, although some research is now emerging.

One study published in the publication ‘Science’, based specifically on Twitter looked at 126,000 news stories tweeted by over 3 million users over ten years and found that the truth cannot compete in the online space with speculation, rumour and lies.

The reason education is the only solution to this issue is perfectly captured by MIT Data Scientist Soroush Vosoughi who has studied fake news since 2013 and stated “It seems to be pretty clear that false information out-performs true information, and that is not just because of bots. It might have something to do with human nature”.

One of the most interesting aspects to the work of Vosoughi and others is the finding that bots spread true stories as often as they spread lies. It’s clear that to address this issue we need to focus on people, not technology. For fake news to become malignant, it has to spread and that takes human intervention and judgement, or lack of.

Fake news requires the right conditions to grow, and the perfect conditions are a core population lacking basic digital literacy skills combined with the targeted distribution of propaganda that plays on specific aspects of human psychology as Vosoughi suggests.

As with many diseases, there is a cure, and the cure is education, not regulation. A population cannot regulate its way to enlightenment.

The UK Government has defined ‘British values’ as democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs.

It goes further to place a specific responsibility on educators to take direct action to promote and amplify these values and to challenge any opinions or behaviours contrary to them.

It’s the latter part of those statements that require special attention. Given the spectacular rise of fake news my contention is that it poses the single greatest threat to collective British values that we face.

Furthermore it is my contention that the FE sector represents perhaps our most powerful national asset to combat the phenomenon given its mandate to uphold these shared values combined with its unique place in our education system and wider social communities.

There is both an opportunity and a challenge here for FE. Further education, sometimes referred to as the ‘Cinderella sector’ as the long neglected part of the UK education system, trains more than 2 million people and over 1.4 million of those are adults.

It is widely known and reported that FE is undergoing a sustained funding crisis at the same time as facing increasing demands and costs, and consequently it is not surprising that almost everyone working in FE is seeking additional funding from the UK Government.

In most cases asking for more money simply won’t work, and it certainly hasn’t so far not least because people invest in what they care about, not what you care about, and Politicians right now have fake news high on their radar. We achieve our objectives best when we help others to achieve theirs, and FE can make a compelling case to Politicians to do that with fake news.

Through the delivery of a national, but locally available, digital skills programme as part of a radically remodelled adult education offer our Colleges could make a huge impact in the context of national digital literacy. The success of the Google Digital Garage programme has highlighted the enduring power of physical place and social interaction in the digital age, and Colleges are no different.

The conditions for fake news to grow have been there for some time. The fact that the UK has a national digital skills crisis is nothing new with the Science and Technology Committee back in 2016-17 calling it a ‘crisis’ highlighting that more than twelve million adults lack basic digital skills, and the situation has worsened.

Crisis is not a word you typically see adorning the cover of reports like this. What is needed now is action.

The political conditions required to support such an initiative are there if FE were to make a collective and collaborative case to deliver the solution.

Fake news can only become fake news when people engage with it and share it. Blaming a tool like Facebook for spreading fake news is like blaming a packet of cigarettes for spreading cancer. Well intentioned but misplaced. People only stop smoking if educated to do so.

A wealth of data shows the correlation between education and health, and the appropriate use of technology is no different. It can be a force for good, or bad, and what makes the difference is our ability to exercise good judgement in a digital world.

For fake news to amplify an individual must lack the basic digital literacy skills that would enable them to identify characteristics likely to indicate it’s fake news. Logically the only solution to this national problem is education, and specifically education of a wide cross range of social demographics, the very thing that FE does so well.

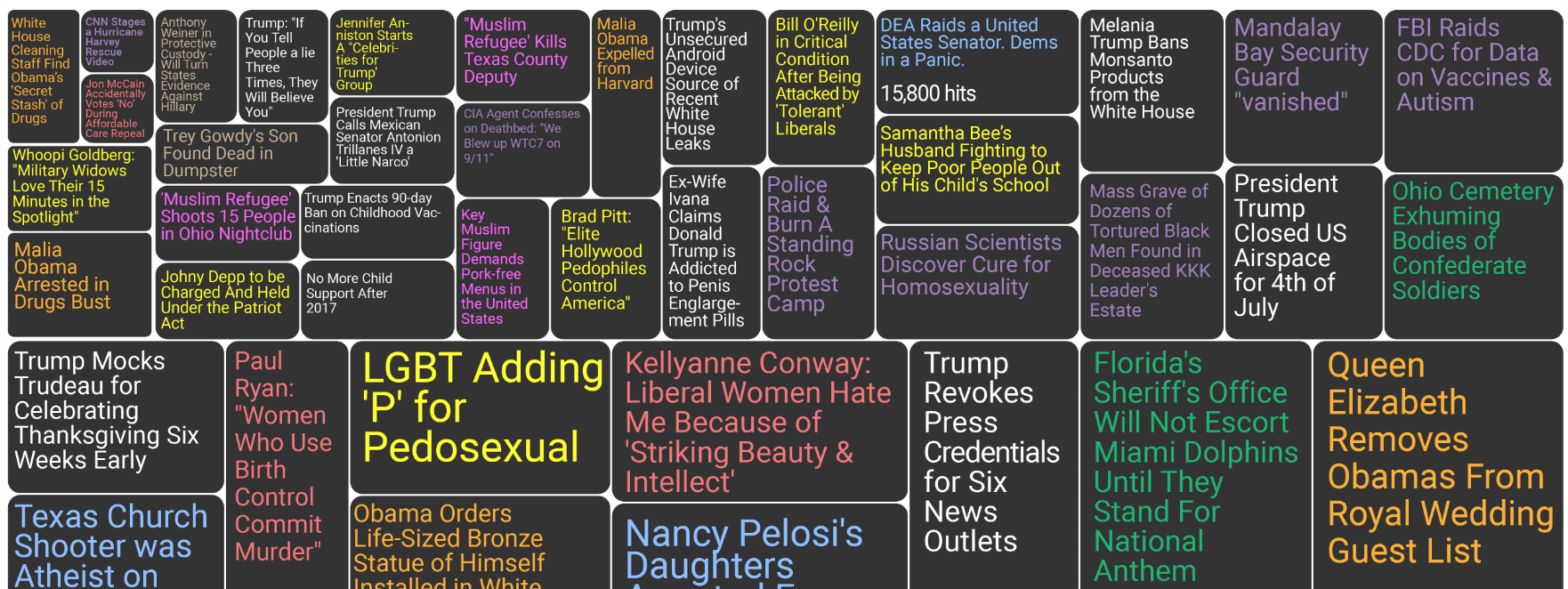

The data visually represented in the image below was compiled based on the largest fake news stories circulated in 2017 and provides an indication of the some of the most widely amplified and circulated fake news stories at that time.

They range from funny to offensive, but without the key digital literacy skills to identify them as such they can exploit ignorance and fear to become something far more serious for our national health and the critical role of British values in the prosperity and wellbeing of the nation.

Addressing digital literacy skills across the whole of society, but especially among working adults and those retired, is in the national interest.

As we move through unprecedented times of political, social and economic uncertainty with an increased threat of social unrest, it has never been more important to invest in our Colleges to deliver education and skills training aligned to national priorities.

Digital literacy can be defined in a number of ways but broadly takes the form of specific common themes including the development of a core set of competences required to participate effectively in the digital world.

This can cover the skills, knowledge, characteristics and behaviours to make effective use of digital tools for the purpose of effective collaboration, expression, communication and knowledge acquisition.

In many ways digital literacy is nothing new in education with agencies such as Jisc and many others providing a wealth of material and support for educators on this topic going back a number of years.

However it is my contention that most of the effort to date has focused on the more technical and operational aspects of using a range of technologies to ensure digital engagement, rather than the now equally critical aspect of digital wellbeing aligned to online behaviours.

Colleges can play a critical role in ensuring that digital literacy is embedded within core activities enabling people to exercise good evidence based judgement in a digital world, and in doing so maintain sound digital health.

With the right funding and policy support, Colleges could expand this work and influence to create advocacy for ‘British values’ linked to protection against fake news. It requires the political will, vision and resource allocation, then leaving Colleges to get on with it.

There are no viable alternative solutions and the scale of the problem is vast. Analysis by the Centre for Economics and Business Research has indicated how the UK could pay a big price for the rising number of people lacking basic digital skills, costing billions of pounds in lost productivity along with social and economic deprivation. Failure to address this will mean that the threat posed by fake news will only continue to rise.

The logical solution to this issue is to directly prioritise and invest in core digital skills that cover both the functional digital skills required to meaningfully engage with the digital economy but also equally important to civically engage with digital society.

The Centre for Economics and Business Research also revealed that whilst over 96% of those aged 15-24 possess basic digital skills, this drops to less than 55% for those aged over 60.

My contention is that this has profound implications for the maintenance and promotion of ‘British values’ as huge numbers of the UK population are likely to be vulnerable to fake news (the over 55 age category is the fastest growing demographic on Facebook for example).

Whilst propaganda has been around for a long time, cyber propaganda is a relatively new phenomenon and the potential impact is greater than any in history due to the ability for it to amplify and spread like a digital virus.

As the UK Government begins to comprehend the dangers of fake news there is increasing recognition that this trend must be countered and actively fought. Whilst the majority of the attention is aimed at the actual technology platforms, this is political convenience rather than an intellectually robust response that will work.

This gap presents an opportunity for FE to cohesively align to offer a solution that is genuinely effective against the rise of what former US President Obama has called the ‘dust cloud of nonsense’.

There are examples of the way forward already present in the FE community. Innovative educators like Scott Hayden, a Digital Innovation Specialist and Lecturer in Creative Media Production at Basingstoke College of Technology is an example of delivering engaged online learning communities in open debate about salient issues, bridging the gap between the inner world of education and the outer world around it.

Scott is very much an example of preparing people to both use digital tools wisely and to make a positive and original contribution to the digital global village in a way that has value.

Thank you @sociallym for sharing your insight into the importance of professional #DigitalReputation today with the @creativestudiosbcot 1st yr students #bcotpro #li

We typed questions to Matt using #FBlive as he advised us on #socialmedia use as profes… https://t.co/G2wQQQ22Mf pic.twitter.com/214eF81B4H

— Scott Hayden (@scottdhayden) October 30, 2018

Whilst arguments about who is responsible for combating fake news will continue FE has an opportunity to make a compelling case to Government for funding to deliver a critical part of the solution:

- Colleges already train millions of adults.

- Colleges are already embedded within their local communities.

- Colleges are already equipped to deliver on this agenda.

What is perhaps required is a new and much enhanced adult education funding stream to target digital literacy for the millions of adults lacking basic digital skills, and to then let Colleges get on with it without interference or an obsession for metrics and measurement.

Just as you cannot grow by measuring your height ‘British values’ cannot be defended through an industrial model of measurement or well intentioned policies that miss the target.

The national prize for supporting Colleges in this mission is billions of pounds of increased productivity, a reduction in the demands placed on the National Health Service (not least as a reduction in loneliness experienced by many as a result of digital exclusion and a major health issue), a reduction in crime (specifically cybercrime), and a more engaged, socially cohesive healthy society less likely to spread fake news.

The prevailing dogma that FE is all about skills is a great injustice. It’s far more important than that. Further Education provides second chances, it opens doors and transforms life chances for those most in need of it. It creates people who save lives, help others, start businesses and build things.

It supports civic engagement and challenges prejudices. It raises aspiration and supports equality. It creates the kind of people we want to meet in a community we want to belong to. FE didn’t need to be directed to uphold ‘British values’, it has been living them for years.

It’s inherently in our national collective interest to fund it to deliver a national programme of digital literacy that supports civic engagement, tolerance, respect, shared purpose and digital wellbeing.

If we get this right we will live to see the decline of fake news on the social networks and online spaces we are part of, and if resourced appropriately Colleges have the collective power to make it happen.

Jamie E Smith, Executive Chairman C-Learning

Responses