The Social Impact of Apprenticeships – A South African Perspective

South Africa is known as one of the most unequal countries in the world, reporting a per-capita expenditure Gini coefficient of 0,65 in 2015 [1]. In addition, substantial gender and race differences exist in the economy with unemployment rates among the black African (38,2%) population group higher than the national average or 34.4%.

Black African women are the most vulnerable with an unemployment rate of 41,0%.[2] Unemployment amongst young people aged 15-24 years and 25-34 was recorded at 64.4% and 42.9% respectively.[3] These high unemployment ratios have led to a greater dependence on social grants in the bottom 60% of households[4].

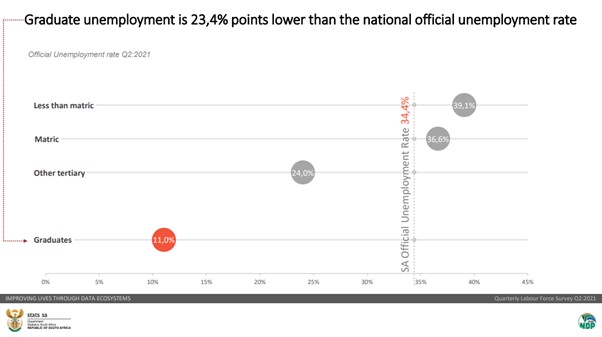

Unemployment in South Africa shows a correlation with levels of qualification, with post school qualifications reflecting lower unemployment rates [5]

The South African Government compiles a list of scarce or critical skills and a number of artisan trades are listed. This has led to a number of artisan development programmes and allowed substantial funding to flow to the training of apprentices.

Apprenticeships in South Africa are supported by agreements between the trainee apprentice, the training provider and the host employer (for work experience) and is governed by applicable South African Labour Laws.

This is important as it provides protection to the apprentice, including the payment of stipends during the contracted period. In most instances stipends are funded by Sectoral Training Authorities as part of their mandate. Payment of stipends is a crucial element of successful training programmes in South Africa as this enables candidates to pay for transport to attend training and reduces programme drop out rates.

In South Africa apprenticeship training combines theory and simulated practical’s (in colleges) and work place experience. Importantly work places must be accredited as such and must have a qualified artisan to mentor the apprentice. Once the apprentice has completed their training, they undergo their trade test and if successful transition to an artisan.

Apprenticeships in South Africa have various social impacts, these can be grouped into

- Employability into self-employment or formal economy

- Confidence and self-belief

- Gender and social inclusion

- Infrastructure support and maintenance

1. Employability

The structure of apprenticeships with a combination of work experience and training results in young people that are ready for the world of work than young people completing traditional qualifications. This is supported by formal employment rates of 79% and self-employment rates of 2%, after artisan completion[6]. Of those employed, 85% were employed by the same company they completed their work experience at proving the value add to organisations[7].

Of those employed who were willing to disclose earnings, over 20% were earning between R11,000 – R15,000 per month against a minimum wage in South Africa of less than R4,000 per month[8].

Additionally young people not absorbed have technical skills that enable them to work as entrepreneurs. A 2019 survey of the plumbing industry estimate that there were 125000 self-identified plumbers in South Africa with 12860 and 10 539 respectively being own account workers or employing 1-2 people[9].

With South Africa’s extremely high unemployment rates there is a substantial impact for every person employed. A commonly quoted statistic is that for every person employed in South Africa 6-7 people are supported by that salaried employee. If we look at actual statistics the number employed in Quarter 4 of 2020 was 15 million[10] people of a total estimated population of 59.62 million[11] we can assume an employment : support ration of close to 1:4

2. Confidence and self-belief

Confidence and self-belief in young people can be greatly enhanced by the combination of technical skills and work experience learnt during the apprenticeship programme allowing those who are not employed at the end of apprenticeship to find other opportunities. In Harambee programmes this is enhanced by ready to work programmes that prepare young people for the world of work.

3. Gender and social inclusion

In apartheid South Africa black people could not become artisans (This could partly explain the number of self-identified unregistered plumbers quoted above). Artisan completion tracer studies show that 75% of respondents are black Africans and 20% are female[12]. This is critical as it raises awareness of artisanship as a career in parts of the population where this was not considered an option and assists with changing perceptions around artisans, especially that artisan jobs are not for young people or women.

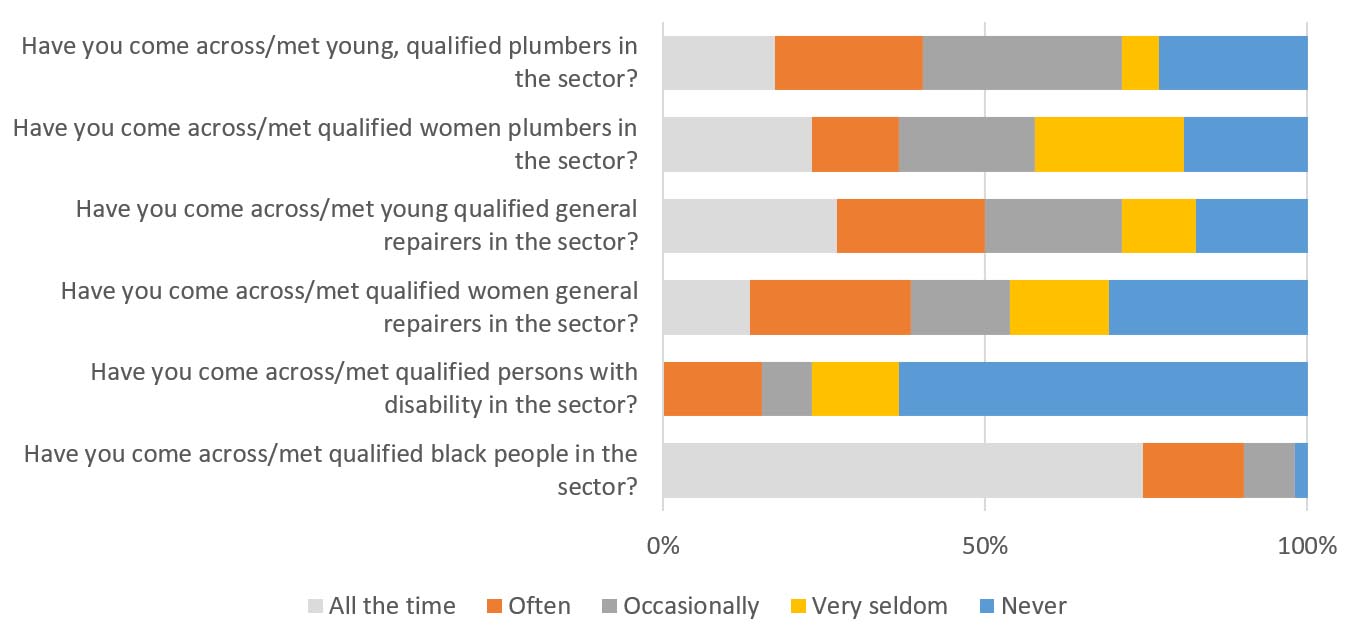

Preliminary insights from some Harambee programmes show most respondents think that women can be great artisans, but they also acknowledge that there are difficulties with accepting women in these roles, by team members, employers and by clients. In relation to ‘visibility’, respondents were asked how frequently they ‘encountered’ certain groups in their work. As shown below (again responses from both programmes are combined).

4. Infrastructure support and maintenance

In poverty-stricken areas artisans have the power to help to improve not just the economy (by contributing to the building and maintenance of infrastructure, but also the living conditions and education levels of their countries. In South Africa there are several projects that leverage artisan skills to assist the community.

One such project in Diepsloot, an area of mixed housing types, from brick houses to shacks assembled from scrap metal, wood, plastic and cardboard, where many families lack access to basic services such as running water, sewage and rubbish removal. The Diepsloot project aims to improve the health of the residents and reduce the ongoing maintenance work for the local WASSUP team (Water, Amenities, Sanitation Services Upgrade Program) by upgrading 10 toilets, taps and drains, and installing better hardware[13]

A second project leverages a 1-week work experience initiative for prospective artisans run by BluLever Education. In this week young people support artisan business to implement repairs and maintenance on behalf of Not-For-Profit Organisations and government schools

The social impacts of apprenticeships are clear and substantial.

These benefits are more likely to be achieved if the following key learnings and lessons are incorporated into apprenticeship programmes:

- Artisan development programmes should be well-structured with clear objectives and outcomes articulated in the contractual elements

- Programmes should be well-funded and this should include payment to participants during the training period

- Where programmes are linked to industry demand, with industry owning selection of participants, greater employment rates will follow

- Candidates should be prepared for the world of work, including personal mastery and soft skills in collaboration with technical skills, and understand what being an artisan means

- Awareness programmes of what being an artisan means, especially that make use of artisan role models, can be highly effective as a career guidance tool.

Sherrie Donaldson, Director, African Innovators (Pty) Ltd

Sherrie is also part of the Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, Sector Lead: Plumbing and Water, and the South African Brics Business Council, Skills Development Working Group

References:

[1] http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=12930

[2] http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q2_2021.pdf

[3] http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q2_2021.pdf

[4] http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=12930

[5] http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q2_2021.pdf

[6] Department of Higher Education and Training Annual Report on Tracking of Newly Qualified Artisans, Artisan Tracer Study 2018/2019

[7] Department of Higher Education and Training Annual Report on Tracking of Newly Qualified Artisans, Artisan Tracer Study 2018/2019

[8] Department of Higher Education and Training Annual Report on Tracking of Newly Qualified Artisans, Artisan Tracer Study 2018/2019

[9] https://www.pem-consult.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Industry_analysis_of_the_plumbing_industry.pdf

[10] http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q4_2020.pdf

[11] http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=13453

[12] http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=13453

[13] https://worldskills.org/what/projects/sanitation-studio/south-africa/

Responses