Supporting neurodiverse apprentices is a win for all

#LookBeyond

#Apprenticeships are paid jobs that incorporate on and off the job training. Engaging in training may require learning a mix of practical skills, but also still requiring formal assessments and needing some study skills in order to complete, for example, assignments or examinations.

The term neurodiversity, one that is becoming more commonly used, encompasses an umbrella of conditions including, but not limited to, Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Developmental Coordination Disorder / Dyspraxia and Developmental Language Disorder.

Around 1 in 5 to 6 apprentices are likely to be neurodiverse.

Some people who are neurodiverse have specific challenges demonstrating their understanding of new learning to others, some others have challenges with presenting information, and training needs to meet the way they learn best.

Appropriate identification and support can aid the retention of the apprentices. In England apprenticeship providers can draw down Learning Support Funding to help provide this support.

The number of neurodiverse apprentice may well be higher in some professions than others, as certain jobs may attract specific skills and talents. But not everyone comes with a label or diagnosis. Some people may also not feel confident telling their provider they are neurodiverse at the start of their apprenticeship journey. Previous experiences may not have been positive. For others, this may not be a conscious decision not wanting to tell you (although this is a personal choice), but because they may have missed out, not been recognised as, or have compensated for challenges during their school/college days.

Some people will be starting an apprenticeship, and this may herald a return to learning and see this as an exciting opportunity. They may be able to do their current job but are now being presented with the additional need to study. The combination of study, work and home life can for some become all too much. Wellbeing may be impacted. This isn’t to say we should stop someone from undertaking an apprenticeship but provide support to enable someone to balance the demands that may arise.

Screening all not just the selected few

I have heard it said by some providers that they only screen for Neurodiversity and additional learning needs with those who come forward and ask. However, this approach may continuously be missing the apprentices that actually have always missed out on the support they need resulting in them being at greater risk of ‘fall out’.

Neurodiversity by definition recognises the variation in the manner that people present in both their challenges and their strengths. Significant numbers of learners may have left school with lower level qualifications and entered into the workplace, working at lower level jobs because they haven’t had their support in place. Many people may choose to do an apprenticeship as they see it as a practical option to gain skills and progress. The decision won’t have been taken lightly and they may start with feelings of trepidation. Telling providers they may have potential additional support needs may be something they avoid doing as they may be concerned as how they may be perceived.

Never had needs identified till now

Some people will have not been told they are neurodivergent (terms like neurodiversity are only being used more today, and in school phrases such as specific learning difficulties may have been more likely to be used).

When the person begins to study for an apprenticeship, the challenges they have had may re-appear. Someone, who has Dyslexia may find the content and volume of reading difficult and/or the composing and writing of assignments harder to do. New words and expectations from others may not be aligned to the skills set the person has. Learning skills may be assumed to have already been obtained. Gaps in skills which seem trivial to others may become real barriers to progress such as organisational or time management skills. Each person will be different. Someone with Developmental Coordination Disorder may find that learning a new skill takes longer than others to achieve and need more practice and demonstration. This may increase feelings of anxiety and for some feelings of shame and thus avoid discussing it with the trainer.

The context for guidance may also need to be different. Someone working in an office with Dyslexia may have very different support needs to someone working in a shop or in a bakery for example. Adjustments by diagnosis can be limiting for all.

More than statistics!

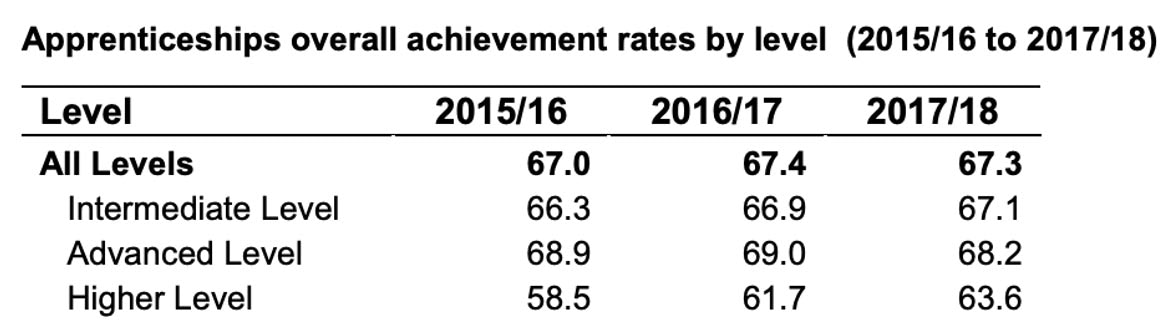

Around 1 in 3 apprentices drop out of apprenticeships or withdraw from their training. Lack of identification may result in lowered self-esteem and the person ‘just’ leaving without explanation. The impact on the person can be far greater than a statistic but can lead to increased anxiety and depression and limit their confidence in engaging in learning again in the future. For the provider it can impact on future payments and attracting new talent to their programmes.

Who may have missed out on having their needs identified?

- 22% of apprentices in the 2020 report in England were over 35 years: Older learners starting an apprenticeship may be more likely to be individuals who may not have been recognised as neurodiverse when younger as there were lower levels of awareness.

- Females: It is only recently that there has been a greater understanding of how challenges present for females and as a consequence woman may have been missed in school and potentially (and inaccurately) thought of as less capable! Also, females have been shown to better at camouflaging their challenges, but this may be instead be presenting as anxiety.

- People who come from BAME groups: Some people may be less aware of traits associated with some neurodivergent conditions and they may also come with additional stigma. Stigma against people with Neurodivergent conditions, particularly Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability, is well-documented in many countries and communities. However, evidence suggests that, within the UK, stigma may be more common in ethnic minority communities. This is important as stigma affects families’ engagement with services and overall wellbeing and quality of life.

- Lacking specific patterns of challenges: Apprentices that don’t fit into neat boxes often get missed by systems that screen by condition not looking at the person’s needs. Overlap of traits in neurodiversity is the rule rather than the exception. Some people do not have a ‘classic’ picture of someone with Dyslexia or ASD for example and so miss out on support all together.

- Those who have been in care (Looked After Children) and those previously excluded from education: SPecific groups of learners at higher risk of becoming NEET (Not in Education, Employment and Training) have much higher rates of being neurodiverse but not having their support needs identified.

5 things you can do as an apprenticeship provider

- Upskill your staff about neurodiversity so they feel confident having conversations with learners and recognising how to support them: We have extensive experience of providing awareness training, e-learning and accredited courses.

- Screen all your apprentices (and not just selected learners) for neurodiversity and take a person- centred approach: We provide robust screening tools used by 10s of 1000s of learners that deliver not only personalised resources but support the learners’ well-being and their study skills and consider their strengths too!

- Goal set with the learner: This is an important step to help the person to prioritise what they need to do to maximise their skills. Often prioritising and planning skills can be a real challenge. By doing this, outcomes can be improved greatly.

- Celebrate strengths with the learner: Our tools allow the person to embrace their spiky profile and be able to discuss what they can do as well as challenges.

- In England you can gain Learning Support Funding: We can help you to do so with quick and easy tried and tested tools designed by international experts in the field of Neurodiversity with more than 25 years of experience. We can make it easy to map all of the processes relating to claiming LSF.

What is the Learning Support Fund?

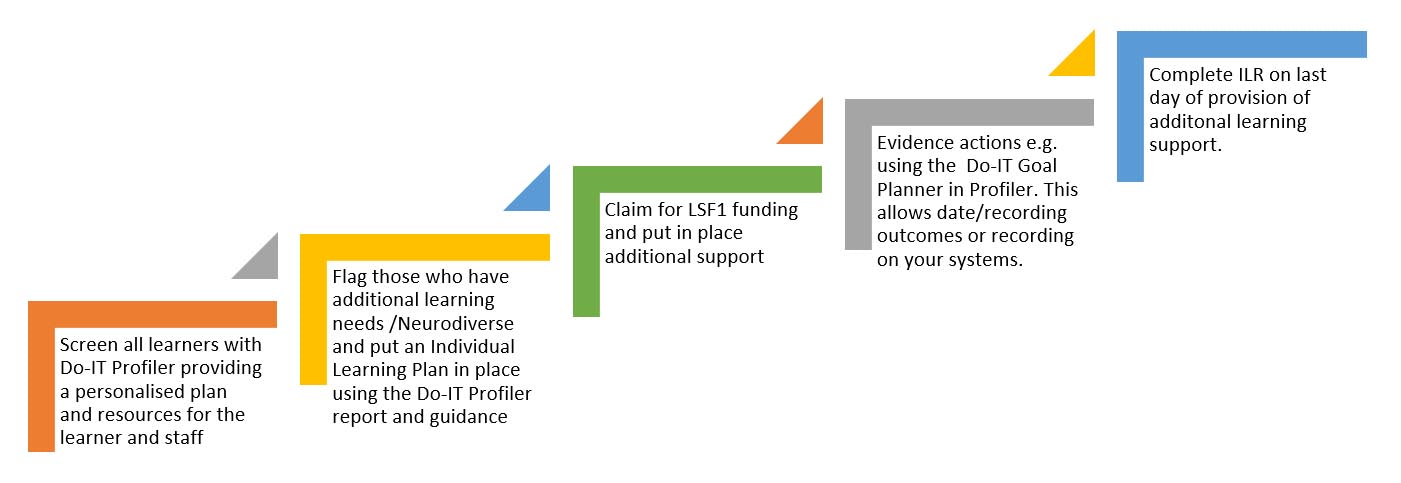

If you’re registered for ESFA funding, you can draw down Learning Support Funding of £150 per learner per month to support learners with additional learning needs. This will enable these learners to achieve their learning goal and allows your organisation to provide personalised support to help them engage and be successful in their apprenticeship and progress in their chosen career.

If the cost of providing support to a learner goes above the total earned from the fixed monthly rate, and you have evidence of the excess, you can claim for this excess through the Earnings Adjustment Statement (EAS). For every month claimed the learner must be receiving support on the last day of the month to receive LSF for that month.

What processes can be put in place to can help all your learners ?

- Screening all learners with Do-IT Profiler allows each person to have resources tailored to their needs including wellbeing and study skills tools. This is not a tick box exercise.

- Specific personalised help (not by label) but for each neurodiverse learner, highlights their talents, allowing them to build on them and minimising any challenges. It considers the environment and context too.

- Information from the personalised reports offers guidance to staff as well as the learner and upskills staff to have confidence in knowing how to best support the learner in a timely manner.

- Tools are included that review progress and put in strategies before challenges present and confidence is lost.

- The result of using the tools can help to increase retention rates.

- The system can provide reports to demonstrate to Ofsted the specific support actions that have taken place.

Professor Amanda Kirby, CEO of Do-IT Solutions

Professor Amanda Kirby is unusual, as she is a GP, experienced researcher, clinician and most importanly parent of neurodiverse children and grandchildren. This provides her with an understanding of neurodiversity and co-occurrence from differing perspectives and a drive to raise awareness and champion best practices. More than 20 years ago she set up The Dyscovery Centre, an interdisciplinary centre of health and educational professionals because of her personal experiences. She has recently retired as a professor at the University of South Wales, and lectured to more than 100,000 individuals worldwide, written over 100 research papers and 9 books which have been translated into more than 5 languages. Amanda is now the CEO of Do-IT Solutions, a tech-for-good company, who have developed unique person-centered computer profiling tools and apps to support neurodiverse children and adults in a range of contexts including education, prisons, and employment settings used nationally and internationally.

Additional references

- Scior K et al. (2013) Stigma, public awareness about Intellectual Disability and attitudes to inclusion among different ethnic groups. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 57(11), 1014-1026.

- Scior K et al. (2013) Awareness of Schizophrenia and Intellectual Disability and stigma across ethnic groups in the UK. Psychiatry Research. 208(2), 125-130.

- Russell G & Norwich B (2012) Dilemmas, diagnosis and de-stigmatizatioin: Parental perspectives on the diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 17(2), 229-245.

- Zuckerman KE et al. (2014) Latino parents’ perspectives on barriers to Autism diagnosis. Academic Pediatrics. 14(3), 301-308.

- Zuckerman KE et al. (2014) Conceptualizations of Autism in the Latino community and its relationship with early diagnosis. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 35(8), 522-532.

- Raghavan R & Waseem F (2007) Services for young people with Learning Disabilities and mental health needs from South Asian communities. Advances in Mental Health and Learning Disabilities. 1(3), 27-31.

- Rousseau C et al. (2008) DSM IV, culture and child psychiatry. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 17(2), 69-75.

- Burkett K et al. (2015) African American families on Autism diagnosis and treatment: the influence of culture. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 45(10), 3244-3254.

- McGrother CW et al. (2002) Prevalence, morbidity and service need among South Asian and White adults with Intellectual Disability in Leicestershire, UK. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 46(4), 299-309.

Do-IT hosts FREE WEBINAR for #ApprenticeshipProviders during #NationalApprenticeshipWeek 2020. REGISTER NOW! CLICK picture? support your Learners and Apprentices.

4 February 2020 12:30-13:00 HRS GMT#apprenticeships #NAW2020 #WednesdayWisdom #FireItUphttps://t.co/sd3aOUQBjy— Do-IT Profiler (@DoITProfiler) January 30, 2020

Responses