UNIVERSITY TECHNICAL COLLEGES – WHAT IS HAPPENING TO PUPIL RECRUITMENT?

Ahhh, another new school year has begun. It is a time of great excitement for pupils after returning from their summer holidays and seeing friends again. For teachers, refreshed and recharged, there is much enthusiasm and promise about what they can achieve for their new pupils in the year ahead. For many school leaders, there is hope, not least that this year will be better than the last.

For school leaders of University Technical Colleges (UTCs), this latter sentiment will apply more than for most. This is because UTCs, first introduced in 2011/12 to promote diversity in the school system through vocational education, have faced a number of challenges since their introduction.

There has been significant public and media criticism of the UTC model, with concerns expressed about their viability, performance and cost. Several new UTCs closed their doors soon after opening, and the main reason cited for these closures was a failure to recruit sufficient pupil numbers to ensure they were financially viable.

In June 2017, the National Foundation for Education Research (NFER) published a research report which examined the available data to assess what was really happening with UTCs. This found that while most UTCs had a challenging start, this was partly to do with the difficult context they were operating in and how they were being judged.

Progress 8

For example, our research suggested that at least some of the poor performance of UTCs in the headline accountability measures may be because the academic measures do not recognise the composition or breadth of curriculum offered by most UTCs. It is good to see that the Department for Education (DfE) has recently acknowledged that Progress 8, their headline accountability measure, is not the most appropriate performance measure for judging UTCs’ performance.

Our research also examined concerns about UTCs’ failure to recruit sufficient numbers of pupils, and confirmed this was a major issue. However, the research also noted that UTCs are trying to attract pupils at age 14, which is a non-traditional age for moving school in England, and were doing so against a backdrop of a reported lack of proper careers advice. To address this, the Government announced new legislation in 2017 requiring local authorities to write to parents with children in Year 9 to inform them about choices and opportunities at age 14.

In the remainder of this feature, we look at what has happened to pupil recruitment in UTCs following this legislation.

What happened to UTC pupil numbers in 2017/18?

The latest published pupil numbers data, which relates to January 2018, shows that the number of UTC pupils increased by 16 per cent compared to January 2017. In contrast, pupil numbers in the whole secondary sector in England grew by just over one per cent over the same time period.

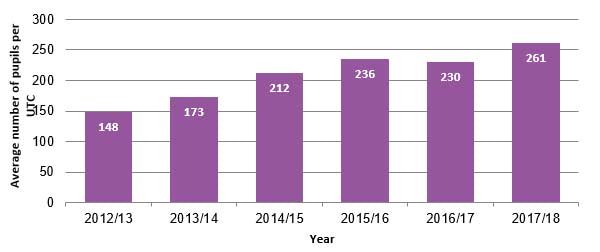

We also looked at what had happened to the average pupil numbers in UTCs, which takes into account the changing number of open UTCs each year. As shown in Figure 1, the average number of pupils in a UTC has increased from 230 in January 2017 to 261 a year later, an increase of 14 per cent.

Furthermore, of the 49 UTCs which were open in 2017/18, we now have one – Aston University Engineering Academy – which is operating at full capacity. This UTC was opened in August 2012, so it has taken six years to reach this point, but they have made it!

Figure 1: The average number of pupils per UTC has increased between 2017 and 2018

We know that UTCs primarily recruit pupils at age 14, so the new legislation is likely to impact on pupil numbers in Year 10. Is there any evidence that the pupil numbers in this year have increased in 2018?

For the 44 UTCs that have been open for at least two years, we find that Year 10 pupil numbers have increased by nearly 20 per cent compared to January 2017 levels.

Furthermore, just over half managed to recruit a record number of Year 10 pupil numbers.

Some positive overall signs, but not for all

Despite these positive signs, not all UTCs had a rosy time in 2018. Three UTCs closed their doors for good and two more closed and subsequently reopened to make a fresh start at the beginning of the 2017/18 school year.

Since then, a further three have announced that they would be making a fresh start in 2018/19, bringing the total number closed / fresh start UTCs to 12 – about 20 per cent of all opened. Most of these were operating well below capacity and not attracting sufficient numbers to be financially viable.

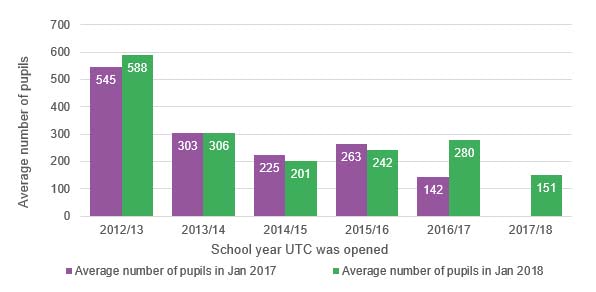

As shown in Figure 2, most of the increase in pupil numbers since January 2017 has been generated by newer UTCs that have been set up in the last two academic years. The five new UTCs opened in September 2017 attracted about 150 pupils on average while those opened in September 2016 enrolled an additional 140 pupils on average in 2017/18.

Conversely, many of the UTCs which opened more than two years ago have seen their average pupil numbers stagnate or fall. Furthermore, only 45 per cent of the available spaces in all UTCs are being filled, with six in 10 UTCs less than half full, which is unlikely to be sustainable in the longer term.

Figure 2: The average number of pupils in older UTC cohorts appears to be stagnating

What might the 2018/19 year hold?

Despite the headline trends in 2017/18 looking good, the picture is still rather bleak for many UTCs. Are there reasons to hope this year will be better than the last? Maybe so.

Firstly, while only 45 per cent of the available capacity was taken up in 2017/18, this was nearly seven per cent higher than in 2016/17. Take up may increase further in 2018/19 as the new legislation only came in part way through the year in 2017.

Furthermore, DfE’s recent acceptance that Progress 8, their headline accountability measure, is not the most appropriate performance measure for judging UTC performance, may also help.

However, it is increasingly clear that it will take some time before most are operating at near full capacity.

The Government needs to think more about how it can support UTCs further with new initiatives in order for them to expand and thrive.

Leticia Veruete-McKay, Senior Economist at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER)

Responses