Can Elephants Gallop? The Imperative for Post Compulsory Education to Evolve Has Never Been More Critical

As the covid 19 pandemic arrived in the UK the incumbent providers of post-compulsory education in further and higher education were faced with a set of challenges unlike anything they had faced before.

One Principal and CEO of a large college described it as like standing on a burning platform, so she had to take a leap.

The leap being referred to was the necessity to rapidly pivot the business model from one built on decades of largely on-campus delivery in physical locations to a new model of largely online digital operations that brought people, processes and infrastructure together in new ways. No small challenge and time was a luxury nobody had. Innovation was a matter of survival and elephants had to gallop.

Over the last year I have had the privilege to work with many leaders transitioning rapidly from an ‘as is’ way of doing things to a very different ‘to be’ one, and just as with many of the commercial companies I work with and study, common themes determine relative success or failure.

Let’s explore a few of them:

Is anti-innovation bias slowly killing you?

Disruption is nearly always more disruptive for incumbent providers like colleges and universities than it is for consumers, and so it was with the arrival of the Covid 19 pandemic. Whether exploring commercial organisations or public sector ones, common themes can be observed time and time again as they relate to those better able, or less able, to manage and prosper through disruption. An anti-innovation bias is one of the most common observations in organisations who struggle.

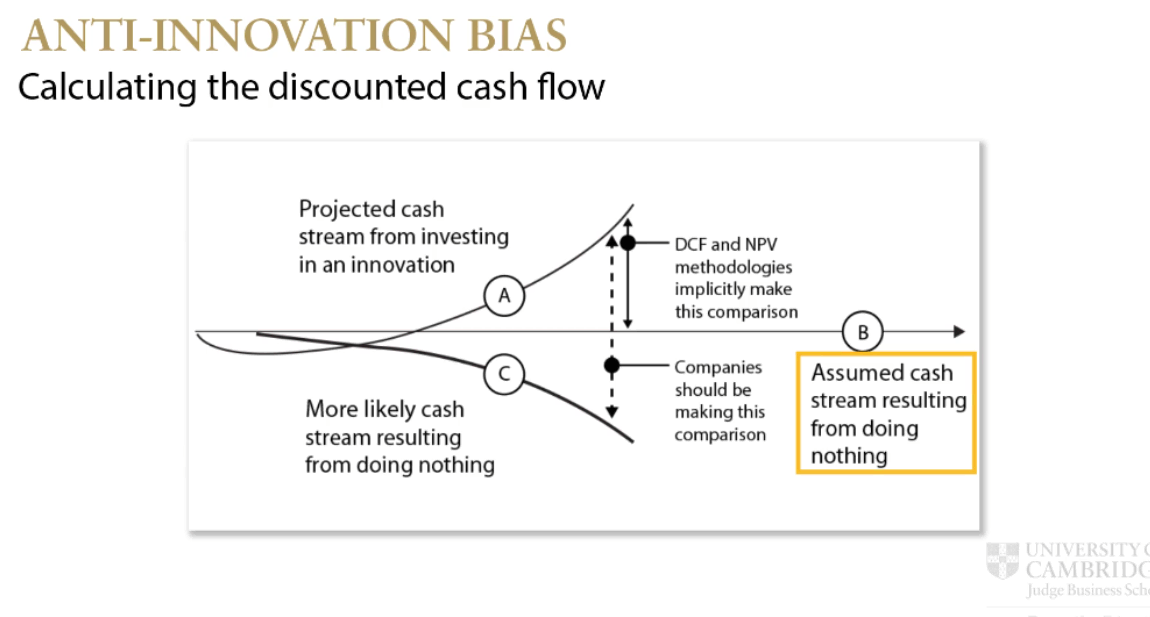

I’m currently undertaking a course on digital disruption at the University of Cambridge Judge Business School and recently one of the lecturers Dr Kamal Munir was discussing anti-innovation bias and sharing insights on how this can impact on organisational performance. It resonated completely with my wider work. On the chart below whilst option A is the strategy perhaps most likely to yield sustainable growth (and often the one less taken) let’s explore lines B and C in more depth because that’s where the main issues arise.

Take line B as the ‘do nothing’ option. Throughout my career in countless boardrooms I have observed leaders regarding option B as relatively lower risk than investing in a new innovative and untested or unproven product, service or similar development because it ‘feels’ less risky. If we’re frank about it, many of us can relate to that because the familiar is always less scary.

But here’s the killer fact. Option B usually turns out more like option C on the lines on the chart above.

The ‘do nothing’ option is far more risky than is generally perceived, and that’s because many of us don’t know we have an anti-innovation bias, but we do.

This phenomenon is in part why it took a burning platform for many leaders in education to take a leap into the unknown and why financial decline can often become a crisis before radical action is taken.

The takeaway here – be more radical. Always. And safety is the new risky. Don’t fall for it.

We’ve invested so much in this, we have to make it work right?

Ever been part of a project where a lot of resources have been invested in it but since it started the environment and market forces change but you carry on regardless because you’ve invested so much?

You’re not alone. Been there, done that.

Just recently I was listening to a senior executive who had secured some funds for a new facility who said ‘well we all know build it and they will come’. I responded by saying actually we now know the opposite, they absolutely will not come unless there is a compelling reason to.

It’s not hard to find many examples of buildings and facilities that cost millions of pounds that failed to be used as intended, stand empty or severely under utilised and have to find a new purpose.

They built it and they didn’t come. This is known as the ‘sunk cost fallacy’ (Arkes & Blumer, 1985) and basically means continuing behaviours as a result of previously invested resources. It’s a very bad idea.

In education this can translate to beliefs like ‘once the pandemic is over students will return to campuses’ etc. Some will, many may not, and for others they will seek out the growing number of employers and businesses who are training their people their way.

Thinking you need a new campus is no different to when Henry Ford said if I had asked my customers what they wanted they would have said faster horses.

The question needs to be asked within the context of radical thinking because across the world, largely driven by technology, the status quo is being disrupted like never before. You might not need buildings in the same way in the digital age, because learning can happen anywhere. Or you may need new buldings, but their purpose might be radically different.

Don’t let the sunk cost fallacy fool you. Continuing to invest in your status quo business model invariably costs more than you think, not least because you’re likely failing to invest in new ways of doing things that will secure your future.

The Essentials Menu – Agility

The future belongs to the most agile. This requires systems, processes and people to be equipped with the ability to pivot business models and ways of working at speed to adapt to a changing environment, just as thousands of educators had to when the pandemic arrived.

Those who had already invested in flexible cloud based technologies and the training for their people to use them with confidence did a lot better than those who had not. Across the business world it is no different. Incumbent providers of services and products are facing rapid disruption and only the agile will survive.

Picture credit: Ross Findon.

What would it take to kill you?

Busy leaders often don’t spend enough time considering this question. If you’re running a college or a university, what would it take to kill you?

Right now I know of many colleges who went all in to pursue the apprenticeship business opportunities and are now facing a financial crisis as a result of the pandemic taking a wrecking ball to that business model.

Same for those colleges and universities who have large commercial facilities now standing empty (I know many providers who went all in for both apprenticeships and commercial facilities and because of the specifics of those areas now face a crisis).

In the curriculum, huge disruption is now taking place. I was only recently listening to some people talking about how they had been forced to cut their own hair during lockdown and how they had done quite a good job so they will continue to do it that way (bye bye hairdresser).

Running a hair and beauty salon in a college? You might want to put on a ‘cut your own hair’ course next week, and do it online. I will be your first client.

Picture credit: Birger Strahl

Develop new foundations for competitive advantage.

The course I am currently undertaking is a great example of this. The timetable is almost entirely flexible. I can take a lecture at 10am on a Monday, Thursday afternoon or Saturday. I just beam in at a time that works for my busy lifestyle.

If you’re telling your students to attend a lecture at 10am on a Monday and that’s it, you have no excuse if you’re disrupted and have your lunch stolen. New foundations for competitive advantage are essential now.

Develop new business models.

If your college or university is too reliant on Government funding be it apprenticeships or similar you’re vulnerable. Education is the biggest market in the world. There is no shortage of opportunity to develop new ways of doing things in terms of products and services if you reimagine it. Radical thinking will be required.

The sector is strewn with examples of business villages where the idea was to nurture new start ups to link to students, but too often this just became rented office spaces representing old thinking that wasn’t particularly effective the first time and that’s why most business villages were a complete waste of time and money with little to no impact.

If colleges and universities want to change this then community driven innovation is a prerequisite.

Building a business village or equivalent? Are businesses and students building it, or is a working group of senior managers in the organisation doing it?

If it’s the latter it will almost certainly fail to live up to expectations.

Don’t be too accountable to anyone.

Many organisations have faced difficult times because of the power of a particular stakeholder. If you have a stakeholder with too much influence, you are delivering their strategy not yours. An example from the business world would be the Harley Davidson company.

As its market forces shift more towards efficient and more sustainable motor vehicle technologies, Harley Davidson has found itself in danger of becoming a dinosaur. Its traditional and current customer base have not responded well to its attempts to move towards electric powered motorcycles and the company appears to have lost its nerve, backing away from a bold vision for a strategy that it believes is the future and instead arguably reverting to servicing the needs of an existing customer base that seems to dominate its thinking (and too much power over its strategy).

In doing so, Harley Davidson, once a brand thought to be bullet proof, is showing signs that it might not be as strong as it thought.

If you don’t have the courage to deliver your own strategy, you’ll end up delivering someone else’s and it won’t end well as you fall into the sunk cost fallacy and all the financial problems that come with it.

If you instinctive reaction to the point above was ‘but we are funded by the Government’ I would encourage you to think about that in the context of the central purpose of this article.

Robust financial management and strategic planning processes.

This one seems obvious right? So why does it go wrong so often? When I am working in organisations that are facing severe financial pressures and it comes to the finances there are common themes that can be observed time and time again. Overly ambitious projections, opinions over data, unconscious bias imacting on decision making and so on. Open trust and transparency is essential for robust financial planning as often you’ll be faced with stark scenarios that present big challenges, but without it the foundations of the house are built on sand. I once led an exercise based on wisdom of the crowds methodologies that asked several hundred staff, most with no financial expertise, to predict a range of financial scenarios for the organisation going forward. It turned out to be vastly more accurate than anything the small team of finance specialists could have modelled by themselves. To take control of your financial future, you have to let go of it and trust the community you serve, and more importantly, authentically engage them in the co-creation of your products or services.

As I look around the wider commercial sectors and the rapid disruption taking place, since those organisations are the destinations for many future graduates there is inevitable causality with the post compulsory education sectors because unless that change aligns there will be one hell of a mismatch, and the threat is that post compulsory education ceases to be relevant at all. Whilst elephants can’t gallop, they can fall and when they do, they fall fast.

Take a couple of elephants from industry.

Primark, a massively successful retailer that recently announced it had lost more than a billion pounds of potential revenue because it doesn’t have an effective online shop. Perhaps more surprising is that it has stated it doesn’t intend to have one either. A bold move and one that places it squarely in danger of the sunk cost fallacy.

Whilst I am sure that in a post pandemic world there will be a bounce for the likes of Primark it may be a temporary one. They need to check their thinking to make sure it’s not what economists would call ‘dead cat bounce’ (you drop a dead cat from a height and it will bounce, but the cat is still dead. You get the idea and apologies to cat owners for that metaphor).

Or take a business like WeWork. The idea was that business owners needed flexible office spaces in premier city locations and for a while this business was growing rapidly and then the Covid 19 pandemic arrived and with it a strategic shift to distributed working models.

WeWork may continue to do well, but the concept of the office is not what it was. Its future will be determined by its ability to disrupt again.

Be the disruption you wish to see in the world.

I may have paraphrased that from someone with a far greater mind than mine, but the point is relevant. If you’re not the disruption, you will be disrupted, and it’s better to be the former. We are living in a time of what David Price OBE in his book ‘OPEN, How We’ll Work, Live and Learn in the Future’ referred to as ‘disintermediation’ where people are increasingly going directly to whatever service they want, and thanks to the internet they largely have the ability to do it in most cases.

David’s follow up ‘The Power of Us’ takes a number of these concepts further and provides almost a manifesto for change for those leaders who are serious about being the disruption rather than having it done to them. Check it out as insights on how to navigate to your preferred future are contained with it.

As our environment changes at an accelerated pace with all of the bad (climate change) and good (opportunity to work in a smarter more sustainable way) factors shaping our world, for educators just the twin forces of cloud technology and distributed working patterns alone will radically disrupt the post compulsory education sectors, aside from the wider forces we could explore.

For evidence of the scale of the disruption just look at the high street. Barely a week passes without some retailer or another asking the Government to tax or otherwise limit the disruptors because it’s ‘killing the high street’. The bottom line is, the high street is killing the high street. Henry Ford would be laughing from his grave to hear the modern day pleas for the equivalent of faster horses. It won’t end well for them. You can’t stop disruption anymore than you can go back in time. Nostalgia may have its appeal but even that’s not what it used to be (yes we are setting the bar low now but if you’ve got this far carry on).

Amazon was once an online bookstore, but it evolved rapidly and had the agility to become everything from a leading cloud services vendor to an entertainment streaming service to rival the incumbent cinema chains and disrupt their worlds into near extinction alongside Netflix and Disney.

If you’re running a college or a university in an environment where your customers will increasingly have choice, you don’t want to have your Blockbuster moment. I live more than 140 miles away from the university where I am currently enrolled and it doesn’t matter, and I didn’t apply through a third party like UCAS and at last count there were about 200 people on the course. Oh and we all paid quite a lot of money to do it. If most of the recruitment to your college or university is still from your immediate or contiguous region, why?

We are living through an extraordinary time where conventional thinking and conventional business models are being turned upside down and disrupted like never before. If you find yourself thinking it’s just due to the Covid 19 pandemic and beyond that we can all get back to the way things were, you’re likely to be disrupted in a way you may not like.

A recent study by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) warned that 13 of the UK’s current universities are at risk of insolvency.

The actual figure is likely more. Similar forecasts could be made of a number of further education colleges in the UK also. Simply asking for bailouts will neither work or be the best use of that money unless there is clear evidence of a robust strategy aligned to creating disruption that will generate new growth.

For anyone thinking the challenge is massive, well yes and no. Oil giant BP is a bit bigger than most universities or colleges and yet its CEO is pivoting it’s entire business with a bold and radical strategy to not only be carbon neutral by 2030 (yes just nine years away and yes it’s an oil giant) but its core businesses will pivot to be renewable energy (it’s buying up huge wind farms and more), electronic charging stations as its reimagines the purpose of its extensive garage networks, and global leading renewable consultancy and specialist services.

If a business like BP can adapt in that way and to that scale, any college or university can. Aligning cultural and digital transformation will be key requisites for success. I see this almost every day as I work with organisations undertaking this journey constantly and having a robust understanding of how to leverage these assets in any organisation is critical now.

With the right cultural and digital infrastructure any organisation can prosper through disruptive times. Get that right and whilst the incumbent elephants may not be able to gallop, they can certainly move fast enough to have a sustainable future, and I hope they do.

Jamie Smith, Executive Chairman, C-Learning

Responses