EPI Annual Report finds the education disadvantage gap has widened across all educational phases since the pandemic

New research published today (Monday 18th December) by the Education Policy Institute (EPI) shows that the attainment gap between poorer pupils and their peers has widened across all educational phases since 2019.

The analysis, based on attainment data from 2022, shows that the pandemic continues to cast a long shadow over the attainment of young people, but that these impacts have not been felt equally, with some student groups falling further behind their peers.

In the second and final instalment of EPI’s 2023 Annual Report, researchers focus on how attainment gaps vary by gender, English as an additional language (EAL) and geography, as well the attainment gap for students in 16-19 education.

This research builds on the first phase of EPI’s Annual Report published in October, which found record attainments gaps for young children with special educational needs and no progress over the last decade in tackling the attainment gap for children who are persistently disadvantaged.

Key findings from second phase of 2023 EPI Annual Report:

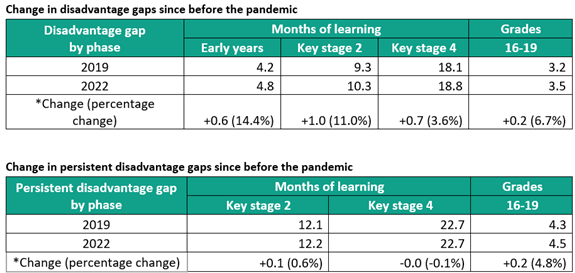

- The disadvantage gap has widened since 2019 across all phases of education, including the 16-19 phase.

- The gap for disadvantaged students at the end of 16-19 study is the widest ever recorded in comparable years since our series began in 2017. Disadvantaged students at the end of 16–19 study were 3.5 grades behind their peers across their best three subjects in 2022.

- The 16-19 disadvantage gap was wider still for persistently disadvantaged students, who were 4.5 grades behind their peers.

- Disadvantaged pupils in London continue to have higher attainment than anywhere else and this gap with the rest of England grows across education phases.

- There are some signs of promise from the government’s flagship Opportunity Areas (OAs), notably during the primary phase. However only Oldham has managed to narrow its disadvantage gap across all phases between 2016 and 2022.

- The gender gap for GSCE students (across English and maths) was 5.0 months in favour of girls in 2022, the lowest gap on record since the series began in 2011. Girls were almost 10 months ahead in GCSE English with a negligible gap for maths.

The tables below show how the disadvantage gap in education has widened since 2019 for disadvantaged and persistently disadvantaged pupils:

*Figures may not sum due to rounding

The attached data tables contain the size of the attainment gap for disadvantaged pupils at each phase of education in each region and local authority, as well as the change in the gap between 2019 and 2022.

Policy recommendations

The second phase of EPI’s annual report includes new recommendations for policymakers:

- The government should introduce a student premium in the 16-19 phase, similar to the pupil premium at key stage 4. This additional funding should be weighted towards persistently disadvantaged students.

- The Department for Education (DfE) should explore international evidence on best practice from nations that have secured high quality educational outcomes whilst limiting gender gaps.

- The government should introduce a ‘late arrival’ premium for schools to provide intensive support to address the large attainment penalties for pupils with English as an additional language (EAL).

- The government should improve data collection for EAL pupils, including the reintroduction of mandatory assessment of English language proficiency and publishing pupil attainment data broken down by time of arrival, first language, ethnicity, and proficiency in English.

- The government should publish an impact evaluation of the Opportunity Area programme and use this to inform policy development on place-based approaches to tackling social mobility.

Natalie Perera, Chief Executive of the Education Policy Institute, said:

“Today’s report continues to shed light on the striking and growing inequalities that are faced by many vulnerable young people. At every phase of education, the gap between children from disadvantaged backgrounds and their peers is widening. This is particularly the case in regions outside of London, where the attainment of disadvantaged pupils has not kept pace with the capital.

“This report serves as a warning to all political parties that education and tackling inequalities must be a priority as we head towards a general election. As well as evaluating its own “Opportunity Areas” the government must consider how to address growing regional disparities as well as targeting resources to disadvantaged 16-19 year olds and newly arrived migrant children.”

Sam Tuckett, Associate Director for Post-16 and Skills at the Education Policy Institute, said:

“Our research exposes concerning inequalities in the outcome of students in 16-19 education, with disadvantaged students facing the largest attainment gap relative to their peers in comparable years since 2017. This disadvantage gap has increased across all qualification types since 2019 and for students experiencing long-term poverty, the gap is even wider.

“These findings show that the government must take bolder steps to tackle widening inequalities in post-16 education. These should include a new ‘student premium’, like the pupil premium available in secondary school, to support the most disadvantaged students.”

Detailed Findings

16-19 students:

- Disadvantaged students at the end of 16–19 study were 3.5 grades behind their peers across their best three subjects in 2022. This is the widest this gap has been in comparable years since our time series began in 2017.

- The 16-19 disadvantage gap was wider still for persistently disadvantaged students, who were 4.5 grades behind their peers.

- Differences in the qualifications that students from different backgrounds entered was a key driver of the overall 16-19 disadvantage gap widening during the pandemic, with A-Level students benefitting from more generous grading. However, in 2022 the disadvantage gap increased across all qualification types compared with 2019.

- In the 16-19 phase, all ethnic groups which had average attainment greater than that of White British students in 2019, had extended this lead further by 2022.

- There has been some progress in closing the 16-19 SEND gap since before the pandemic. In 2022, students with an identified special educational need or disability were around five grades behind other students, compared to 5.2 grades in 2019.

Geography:

The report includes new interactive geographic tools for understanding how disadvantage gaps vary across England. The 2022 data finds that:

- Disadvantaged pupils in London continue to attain better than anywhere else and this gap with the rest of England grows across education phases.

- The West Midlands also stands out as the region with the second smallest disadvantage gap across phases.

- The regions with the largest disadvantage gap at each phase were the North West at age 5, the South West at age 11, and the South East at age 16.

- The South East goes from having a gap that is similar to the national average at the end of reception to having the second widest gap by the end of primary school and the widest gap by the end of secondary school.

- At a local authority level, Newham has one of the smallest disadvantage gaps across phases nationally, and outside of the capital, the same is true for Slough. In the 16-19 phase, Southwark has the smallest disadvantage gap.

- By the end of secondary school, there are particularly large disadvantage gaps in Torbay, Kingston-upon-Hull and Blackpool, recognising that Kingston-upon-Hull and Blackpool are also among the fifth most deprived local authorities in England.

- There are some signs of promise from the government’s flagship Opportunity Areas (OAs), notably during the primary phase. However only Oldham has managed to narrow its disadvantage gap across all phases between 2016 and 2022, at a time when the national gap was consistently widening across phases.

Gender:

- Girls outperform boys across all educational phases, but these gender gaps are not unique to the English education system and point to common challenges in supporting boys’ literacy outcomes.

- The gender gap is unusual in narrowing during the primary school phase – before widening again during secondary school.

- At reception (aged 5) girls were already 3.2 months ahead of boys in 2022, an increase from 2.9 months in 2019. Girls outperformed boys in all key learning areas but, historically, this is most marked for literacy (especially writing) and least marked for maths.

- By the end of key stage 2, girls were 2.1 months ahead of boys in 2022, a smaller gap than in 2019 (of 2.4 months). Looking at reading and maths separately, girls were 5.5 months ahead in reading, whereas boys were 2.0 months ahead in maths – meaning boys overtake girls in maths during primary school

- The gender gap for GSCE students (across English and maths) was 5.0 months in 2022, the lowest gap on record since the series began in 2011. Girls were almost 10 months ahead in GCSE English with a negligible gap for maths, indicating that during the secondary phase, girls pull further away in English and fully catch-up with boys in maths.

- In the 16-19 phase female students have consistently achieved higher grades than male students, but this gap has widened since before the pandemic.

English as an additional language (EAL):

- Attainment varies significantly by first language and pupils arriving late to the English state school system with English as an additional language (EAL) incur a significant attainment penalty – similar in size to the effects of economic disadvantage.

- By the end of primary school, pupils with EAL who arrived late to the state school system were almost one year (11.6 months) behind their peers in 2022 and by the end of secondary school the gap was 16.6 months.

- There has been a significant reduction in the attainment gap for late-arriving EAL pupils since 2019.

- However, a key part of this gap-narrowing reflects compositional shifts within the EAL group towards historically high-attaining ethnic groups and away from low-attaining ones.

Sector Response

Geoff Barton, General Secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said:

“The widening of the disadvantage gap is desperately sad but not unexpected. We and others repeatedly warned that the impact of the pandemic was uneven and that disadvantaged children were falling further behind. But ministers failed to respond with an education recovery plan on the scale that was necessary to meet this challenge.

“Schools and colleges have done everything possible to support these children before, during and after the pandemic. But they have had to do so despite inadequate education funding, teacher shortages and a cost-of-living crisis over the past two years which has hit disadvantaged pupils the hardest once again.

“The government had an opportunity in the recent autumn statement to put at least some of this right by making a commitment to greater investment in education and the education workforce. But it barely mentioned schools and colleges at all and has left them facing worsening financial pressures and a deepening recruitment and retention crisis.

“Ministers must act on the EPI’s findings and look seriously at the specific recommendations in this report. In particular, the recommendation for a student premium in 16-19 education to support disadvantaged young people is vital in improving their prospects for higher education, apprenticeships and employment.”

Daniel Kebede, General Secretary of the National Education Union, said:

“Thirteen years of Conservative rule equate to thirteen disastrous years in education policy. A culture of short-termism and short-sightedness, much of it driven by an unwillingness to listen to the profession, has taken a significant toll on the prospects for young people who have grown up during this era.

“Education should be about levelling the playing field for every child regardless of their background to ensure they get an equal chance in life. Yet as this report from the EPI clearly shows, the situation for students from disadvantaged backgrounds is worsening, and the decimation of services makes the dream of a level playing field all the more distant. A lack of rented or social housing undermines life chances. Schools and colleges see the impact this has on their students every day, where they arrive hungry, tired or with unsuitable clothing and shoes for the weather. The unfair and relentless poverty trap faced by so many young people, clearly makes learning harder.

“Schools and colleges do all they can to support those students who are most in need but a teacher recruitment and retention crisis alongside inadequate funding and support services make this task all the harder. The National Funding Formula has siphoned money away from the areas in greatest need meaning the poorest bear the greatest burden.

“It is evident that the removal of the Educational Maintenance Allowance was a critical blow for 16-19 students, and the need for its reinstatement is obvious. Too many disadvantaged students are now having to work increased hours on top of school work to make ends meet and this will inevitably have an effect on their attainment.

“Right now, 4.2 million children in the UK are growing up in poverty. The cost-of-living crisis alongside Government policies such as the two-child benefit cap have plunged the equivalent of 9 children in every class of 30 into poverty.

“Reducing child poverty must be at the centre of any credible plan to deliver good educational and life outcomes for more young people.’’

Professor Becky Francis, CEO of the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), said:

“Today’s report confirms that the link between family income and educational achievement has been further entrenched by the pandemic. Weakening this may seem like a near-impossible challenge, but we mustn’t forget that it can be done. Thanks to the hard-won efforts of schools, colleges, and nurseries, we saw almost a decade of progress on closing the gap before 2019.

“If anything, today’s findings reaffirm just how important great teaching and learning opportunities are for disadvantaged children and young people. For these pupils, every second spent in the classroom in front of a teacher matters. This is why recruiting and retaining staff must be front and centre of any national efforts to tackle the gap.

“But, while schools can – and do – a lot to mitigate the effects of poverty on learning and development, it would be naïve of us not to recognise that factors outside of the school gate – such as access to regular meals and secure housing – also play a significant part in education inequality. EPI is right to recognise that tackling the attainment gap requires a multi-faceted approach. It cannot be left to schools, or one department, in isolation.

“The findings of today’s report should reaffirm our collective mission to reduce education inequality, at every stage of the education system and on a local, regional, and national level. We must recognise that this isn’t a short-term issue, or one that just affects those young people who leave education without the grades they deserve. If we fail to make inroads in the years to come, we risk long-term implications for the future.”

Cath Sezen, Director of Education Policy, Association of Colleges, said:

“I am saddened, but not shocked, to read that the pandemic continues to cast a long shadow over our young people’s attainment.

“At AoC, we echo many of the recommendations made including the introduction of pupil premium for 16 to 19-year-olds, and support for ‘late arrival’ school students. We have also been calling on the government to extend the 16-19 tuition fund beyond next year.

“Many students arrive at college at the age of 16 already significantly behind their peers, because their needs have not been met in the secondary system. Therefore, their time at college is the final opportunity to address this attainment gap and ensure that young people have the best opportunity to succeed in life. The stark findings in this report make additional funding and resource for colleges more urgent than ever.”

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of school leaders’ union NAHT, said:

“Even before Covid, the attainment gap between pupils from more affluent and less well-off backgrounds was a concern. The government had the chance to take the bull by the horns and show real ambition by not only mitigating the impact of successive lockdowns upon children’s learning, but also by taking lasting action to further close this stubborn gap.

“Unfortunately, ministers failed to offer schools and colleges anything like the resources needed, and have still not set out a long-term plan for the National Tutoring Programme, for which subsidies end next year.

“The issue has been further compounded since Covid by rising levels of poverty affecting more families due to the cost-of-living crisis. The government has done very little to attempt to alleviate the impact of poverty on children, and schools are seeing the effects every day in ways that affect their learning.

“The government needs to do far more to address the underlying causes of poverty and disadvantage in the first place. This includes investing in wider services like social care, family support and mental health services, which have all been decimated over the last decade.”

Responses