How #Mentors Can Help Young People GROW Their Skills To Navigate Life’s Odyssey

We must do lunch

I met Andy, an old schoolfriend of mine, for lunch recently.

As the menus arrived, he was telling me how he’s faced with an option of retiring soon. Crikey, time’s flown!

Although he is partially excited by the prospect of early retirement, he is also daunted by getting older and what he will do with all the time.

He’s had a lifetime career spanning over 35 years in numerous managerial posts in major multinational household-name organisations in the retail space. That’s a “lorra lorra” experience!

So, as we considered what dishes to order, we mulled over what he would like to do apart from playing a bit of golf, riding the motorbike and travel… ’well, I’d like to give something back,’ he chirped.

And that was the trigger for me to describe the background to the new mentoring programme we have launched at Kloodle and I thought I’d use our lunchtime discussion as a plan for the three-part mini-series that you are reading.

This is Article 1; it’s about the definitions, the tradition, the history, the research and the models – it’s the framework. Articles 2 and 3 are about digital mentoring and how we do it at Kloodle, with our latest venture with Salford Foundation.

Tradition, Tradition! Mentoring, the Traditional Way

Over the shared platter starter, Andy reminded me that he had done a lot of mentoring in the past.

He started about 20 years ago and being a mentor was lauded in his company as a good thing to do to help your career progression. By acting as a role model, you were shaping yourself for leadership.

A typical scenario was that a junior person would have been promoted to a position of responsibility, such as running a store, at an early age and stage. Andy in his ‘senior’ position would then be expected to bring out the best of the assigned mentee.

By meeting on a regular basis and in his words by ‘troubleshooting; helping to network in the organisation; putting them in touch with the right people in head office, and; setting up meetings.’

This sounded a bit like line management to me, so I asked for clarification and he informed me that the big difference was that he had never met the individual before; thus, by being independent, the junior person felt they could express worries and concerns without fear of reprisals.

Benefits for both Mentor and Mentee

To most people it seems obvious that mentoring schemes can benefit the mentee through practical advice, encouragement and support, learning from the experiences of others who’ve been there done that, increasing confidence through making decisions, developing communication and personal skills, establishing a sense of direction and building a network, to name but a few.

However, it might not be so clear as to what the mentor gets out of it. Well, Andy told me, there are numerous benefits of this kind of programme for mentors.

Having to listen to and present your thoughts to a less experienced person isn’t that straightforward and it means that you need to be able to simplify complex experiences in order to articulate this.

He added that If you did well then they’d move you on to mentor groups so you had to learn to present to an audience, build confidence, deal with question and answer sessions and, above all, be diplomatic and tow the company line whatever your individual misgivings were.

Great self-development training!

|

In support of this, Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook, in her bestseller Lean In, says: “Mentorship is often a more reciprocal relationship than it may appear… mentee may receive more direct assistance, but the mentor receives benefits too, including useful information, greater commitment from colleagues, and a sense of fulfilment and pride.” She goes on to note that if a mentorship programme is done well, then all parties “flourish”. |

So, what is exactly is mentoring then?

Mentoring comes in many shapes and sizes.

The traditional sponsorship-based American model of mentoring focusses on the use of the mentor’s power, influence and authority to act on behalf of a protégé, ‘opening doors’ as it were.

Some mentees need, what Malcolm Gladwell in Tipping Point calls, connectors, who help create relationships between influential people.

Contrast this with the classic model in Europe which emphasises the mentor’s experience and wisdom to help to enable the mentee to become self-reliant and take ownership of their personal and professional development.

Early mentoring programmes focussed on the transference of information from mentor to mentee, that is telling them ‘what to think’, but they have evolved into the facilitation of the development of a learning relationship or helping proteges learn ‘how to think’.

A useful traditional definition of mentoring (according to the academics Anderson and Shannon) is:

‘‘A nurturing process in which a more skilled or more experienced person, serving as a role model, teaches, sponsors, encourages, counsels and befriends a less skilled or less experienced person for the purpose of promoting the latter’s professional and/or personal development.’’

David Clutterbuck, a thought leader and visionary in mentoring says that he believes that the mentor should help the mentee to step ‘outside the box’ of his or her job and personal circumstances, so they can look at it together.That seems self-explanatory.

Andy told me that mentors are supposed to be guides and the mentee trusts them because they’ve ‘been there, done that’.

It is like standing in front of the mirror with someone else, who can see things about you that have become too familiar for you to notice.’ This is the concept of the ‘trusted adviser’.

The many aspects of mentoring

There is also a lot of associated jargon and a litany of terms surrounding the topic as summarised by Dr Kate Philip:

“Mentoring can hold a range of meanings and the terminology reveals a diverse set of underlying assumptions.

“For example, youth mentoring has been associated with programmes aiming at:

- Coaching

- Counselling

- Teaching

- Tutoring

- Volunteering

- Role modelling

- Proctoring, and

- Advising

“Similarly, the role of the mentor has been described as

- Role model

- Champion

- Leader

- Guide

- Adviser

- Counsellor

- Volunteer

- Coach

- Sponsor

- Protector, and

- Preceptor.”

Lots of overlap here.

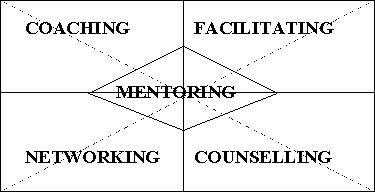

This informative chart below from Clutterbuck and Sweeny demonstrates the many ingredients making up mentoring:

- Part coaching

- Part facilitating

- Part counselling

- Part networking.

|

Directive |

||

|

Intellectual |

|

Emotional Need |

|

Non-directive |

The big question I had for Andy was:

What’s the difference between mentoring and coaching?

Well, Andy explained as the starters were cleared away:

The two are related, like cousins. They have a common purpose but a different focus.

Back to Clutterbuck, who explains that: “coaching relates primarily to performance improvement (often over the short term) in a specific skills area”.

Mentoring has been around a long time

The Oxford English dictionary defines a mentor as “allusively, one who fulfils the office which the supposed Mentor fulfilled towards Telemachus. b. Hence, as common noun: An experienced and trusted advisor.”

These characters originally feature in Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey, suggesting the term ‘mentoring’ has been around a long time, traced back 3,000 years.

In Book 2 of that story, prior to embarking on his mammoth voyage, Ulysses leaves his son, Telemachus, under the guardianship of his long-lasting and trusted friend Mentor.

Initially, Telemachus is described as ‘napios’, which is translated as ‘disconnected’ and suggests he was weak, morally and intellectually.

However, Mentor acts as adviser, teacher and companion in loco parentis. Mentor’s identity is assumed by the powerful and flexible Athena, the goddess of wisdom, courage, inspiration, justice, warfare, mathematics, strength, the arts, crafts and skill. That’s one hell of a goddess!

At the council of the gods, Athena talks about instilling ‘menos’, Greek for heroic strength, probably in this context it means ‘mental strength’, into Telemachus.

Homer is telling us that this is what mentors aim to do, put mental strength into mentees.

This interchange is an illustration of the relationship they develop:

Mentor tells Telemachus: “For you I have some good advice if only you will accept it…”

Telemachus replies: “You have counselled me with so much kindness now, like a father to a son. I won’t forget a word.”

When Telemachus decides he wants to find out where his father is, Mentor, through Athena, acts ‘just like a father’ and promises to ‘help’, ‘through his network of friends’ he organises a crew and ship.

Using his stories, Homer relays a common model of the times of how a young man, disconnected and aimless, a latter day NEET, can be turned into a leader, following in the footsteps of his father, a heroic role model, through expert guidance and nurturing.

All that was a long time ago, ancient history, but human nature doesn’t change.

More recent history

During the ‘age of enlightenment’ in the 18th Century, Fenelon updated the concept of Mentor in Les Adventures de Telemaque, giving him modern day attributes.

There are many other famous examples of mentoring relationships in history, from Socrates to Plato, Haydn shaping the development of Beethoven and Freud to Jung.

Extending that to today, many mentoring relationships hit the headlines.

|

Just recently Ole Gunnar Solksjaer, the Manchester United Manager, said of Sir Alex Ferguson: “He’s been my mentor, but I didn’t understand early on he’d be my mentor. Towards the end, maybe the injury in 2003, I was making all the notes what he did in certain situations… I’ve already been in touch with him, there’s no one to get better advice from.” Telemachus must have uttered similar sentiments about Mentor. |

|

Andy’s Tofu Hanging Kebab had arrived and he wanted to concentrate on his main course, so I decided to take him through the theory of mentoring.

The Theory of the Mentoring Relationship

One of the foremothers of the academic foundations of mentoring carried out in the 1980s, Kathy Kram, Professor of Organisational Behaviour at Boston University School of Management, noted that mentoring involves an intense relationship whereby a senior or more experienced person, called “the mentor”, provides two functions for a junior person, whom she called “the protégé”:

1. Advice on career development behaviours:

To help them ‘learn the ropes’ as it were and get ready for the hierarchical organisation.

It includes:

- Coaching

- Sponsoring their advancement

- Increasing the positive visibility

- Offering challenging assignments, and

- Protection

2. Psychosocial support:

Build on trust and personal relationship to enhance professional and personal growth. This includes confirmation, counselling, friendship and role-modelling.

Kram said: “the mentor relationship can significantly enhance development in early adulthood…”

In her seminal work on ‘The Phases of the Mentor Relationship’, Kram proposed an empirical mentoring model, based on interviews, to explain how that relationship usually progressed.

Her four stages described what happens in any relationship and were assigned the clunky terms:

- Initiation

- Cultivation

- Separation, and

- Redefinition

Kram states that entering a developmental relationship can present an opportunity to stimulate the mentor to channel energy into ‘creative and productive action’.

The challenge benefits the individual by building self-esteem, giving social insight and improving interpersonal skills. Although this is positive, Kram goes on to note that the mentor may feel rivalrous and threatened by the young person’s advancement and growth and this may be the main cause of the breakdown of the relationship.

More recently, using more intuitive terms, the main man Clutterbuck adapted Kram’s model into his Mentoring Lifecycle Model, which works as follows:

The phases are:

- Building Rapport; this is what Kram called ‘initiation’, it is the period of time through which the relationship starts to grow, during which both the mentor and mentee set the ground rules and learn about each other’s competencies. Here, both parties make their ‘commitment’

- Setting Direction; next, the mentor needs clarification of the circumstances and skills of the protegee in order to determine where to focus their efforts and which goals to set. The mentor must be adept at listening carefully, exploring by means of questions and observing. The mentor must focus on what the mentee is good at, keep it positive and set clear expectations. Andy nodded in agreement.

- Progression; this is the period during which both parties gain optimum benefit and the interactions become progressively more fruitful. Kram called this ‘cultivation’. The mentor makes most input at this stage and there is a ‘confidence’ phase through which both parties build trust in each other. The mentor must take a genuine interest in the mentee’s problems so that the mentee can open up to reveal the issues and barriers they face and plans can be made together so that they can act as a team. The mentor can then reach the critical ‘instruction’ phase where the they can be open and frank without offending the mentee. Activities include asking probing questions, challenging views and reflection. The results of any tasks are evaluated by the mentor and feedback or criticism given.

- Winding Up; this is the phase when the relationship changes and the mentee may begin to ‘outgrow’ the mentor. There is a change in the emotional structure of the relationship and the dependency. It can lead to hostile feelings on either side as the original purpose of the relationship has broken down, ‘Separation’ was the Kramism. The relationship has now matured and the mentee can take responsibility for their own actions or ‘self-govern’.

- Moving On; at this point the relationship has finished. There is no longer prolonging, it had come a natural end and both parties must move on.

Overall, the relationship is dynamic and can slip back and forth between the stages.

Students want a Voice of Experience

On our many visits to colleges and through our online survey portal at Kloodle, we have petitioned students for their feedback on various topics, mentoring being one of them.

The general consensus is that the students would prefer to receive careers guidance through an independent expert, someone not connected with the college but with wide industry experience.

They believe it is hard for teachers to be credible when running career sessions as normally their focus is on passing exams and following the university narrative.

Similarly, parents are perceived to push their offspring into ‘safe’, traditional career options, many of which are outdated.

Andy’s a slow eater, so as he nibbled, I decided to present an overview of the research out there.

What does the Research on Mentoring Say?

In the UK there has been relatively little research on mentoring, however, in the US, the world’s leading nation authority on the topic, there has been copious amounts carried out. Although the results may appear tenuous, there are some broad conclusions which can be drawn from the evidence.

It seems obvious to say that mentoring can have a profound, positive impact on mentees, and can help to develop soft skills in young people which raise aspirations and close the ‘aspiration-attainment gap’.

That said, interestingly, mentoring isn’t ubiquitous in practice; according to MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership, one in three young people in the US have never had access to a mentor, many of whom are the ones who would benefit the most.

One of the key analyses of the impact of mentoring schemes was published by DuBois who conducted a meta-analysis (academic speak for a method of combining data from multiple studies) of the effects of 55 different mentoring schemes.

Their overall conclusion was that mentoring programmes do indeed have a significant and measurable impact on the young people who participate, but that the size of this effect is quite modest for the average youth.

However, he also concluded that mentoring programmes offer the greatest potential benefits to ‘at-risk’ young people.

Furthermore, an independent review of studies of mentoring schemes by Jekielek found benefits of mentoring to be:

- Young people who perceive high-quality relationships with their mentors experience the best results

- Overall, young people who are the most disadvantaged or ‘at-risk’ seem to benefit the most from mentoring. Mentored youths are likely to have fewer absences from school

- Better attitudes towards school, fewer incidents of hitting others, less drug and alcohol use, more positive attitudes towards their elders and toward helping in general, and improved relationships with their parents were observed

- The longer the mentoring relationship, the better the outcome

- Youths are more likely to benefit if mentors maintain frequent contact with them and know their families

- Mentoring programmes need structure and planning to facilitate high levels of interaction between young people and their mentors

- Mentoring programmes that are driven more by the needs and interests of youth – rather than the expectations of the adult volunteers – are more likely to succeed

Words of caution: It’s worth noting that one of the key conclusions of many research projects is that mentoring can be successful and have a profoundly positive effect if performed properly, but it can be detrimental if the quality is poor.

A disorganised and unstructured approach generally leads to failure; it means only a few students receive quality mentoring and others, who may have the potential to be stars, have a negative experience resulting in a reduction in inclusion and diversity.

These are all things to consider when developing a mentoring scheme. Next, we’ll look at how to build a strong mentoring relationship.

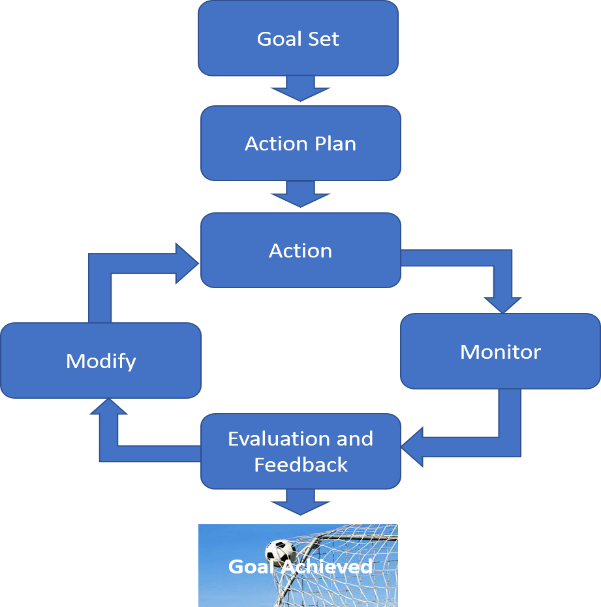

Nurture, care and attention; the GROW model

Probably, the model most widely used in practice to structure individual mentoring relationships is the GROW model.

This basic model was developed by Graham Alexander amongst others in the 1980s.

It’s an acronym, of course, to make it memorable and appropriate because you want the mentees’ confidence and aspirations to grow!

There are numerous other models (named as acronyms) based on similar lines, such as:

- Achieve

- Practice

- Outcomes

- CIGAR, and

- Coach U

The letters in GROW outline the structure:

| Goal | This is what the mentee wants to achieve from the relationship.The goal should be SMART (yes, aa (another acronym!)), that is:

The goals may be organisational, such as being punctual, academic, behavioural or relationships. |

| Reality | The mentor explores where the mentee is at in relation to achieving their goal.They should explore what has happened in the past which could impact on progress. |

| Options | The mentor identifies and assesses the options needed to achieve the goal.This could involve encouraging solution-focussed thinking and brainstorming. |

| Way Forward | The mentor pulls the ideas together to help the mentee conclude and develop an action plan to achieve the goal. |

A major benefit of a productive mentoring relationship is the ‘feedback loop’ built into the process.

In summary, the programme can be depicted as follows:

Andy broke off from his ruminating here to add some comments from his experience; A key point for session structure is that the mentor assumes informed flexibility; depending on the needs of the students, mentors should be relaxed in moving from a highly structured to a less structured approach as the situation suits, not sticking to a rigid method.

Each coaching session should start with a process of reviewing and evaluating the learnings and actions completed since the previous session.

But the trap here for the novice is to spend too much time in the review and evaluate process, opening the possibility of de-railing the main session.

He continued eating and I continued talking.

Neil Wolstenholme, Chairman, Kloodle

This is the first part of a 3 part mini-series. Article 1 is about the definitions, the tradition, the history, the research and the models – it’s the framework. Articles 2 and 3 are about digital mentoring and how we do it at Kloodle, with our latest venture with Salford Foundation.

Copyright © 2019 FE News

Responses