Supporting Organizational Enquiry: A Systems Approach

The Radio 4 documentary Missing Isaiah Berlin (Jonathan Wolff, November 6, 2022) encouraged a small group of experts to discuss the philosopher’s work as a leading public intellectual, well-regarded even 25 years after his death. Acclaimed in the US and UK, Sir Isaiah had a strong interest in Russia, especially it’s political history, but was equally comfortable discussing a range of subjects, whether by book review or in the company of other scholars.

Apparently, philosophical chat via the BBC’s Third Programme from 6pm to evening close-down was popular entertainment for many families throughout the fifties and sixties. One of the regular guest participants on The Brains Trust had the catchphrase ‘Well, it depends what you mean by….’. What did the MIB documentary mean by public intellectual? More than one definition here, but they are usually respected in a particular field, say, economics or metallurgy, and can speculate beyond the level of sound bites in new arenas – G B Shaw, Maynard Keynes and Bertrand Russell all rank as public intellectuals. And they tend to be critical.

Now, I admit I frequently found Professor Berlin’s diction fast and muffled; however, he summarized the role as suited to one who believes strongly in reason and progress, and who holds a moral concern for society. He never saw himself as a public sage, more a scholar who sat on the fence but was ready to talk amiably to those on both sides of the fence. (No doubt – if pressed – as a pluralist he would have acknowledged numerous fences within any one issue).

Somehow, miraculously, given his quota of books, essays and lectures, Berlin found time to listen to more concerts than anyone else, for instance, ‘the deeply beautiful Schubert’; he also confessed a lack of practical skills meant he’d struggle as a desert island castaway. Another struggle mentioned in Professor Wolff’s documentary is society’s notable aversion to folk who seem ‘too clever by half’; practical know-how tends to be given more acclaim.

In the movie Marathon Man (1976) Dustin Hoffman scribbles answers on paper rather than speak out and appear a swot, maybe a survival tactic for lone scholars when sharing classrooms with boisterous peer groups. Fifty years on from this movie, Clare Fox cautions would-be advanced students: don’t expect your contemporary essay or PhD to grab much attention. Modern academic life is creating mountains of material which very few mortals will have time to read, though many specialist groups are eagerly writing for each other, in a manner devoid of public involvement.

Looking back briefly at Berlin’s lifestyle and recent initiatives such as the twenty-minute TED, ‘the thought leader’, and how an intellectual differs from an expert/professional academic, the programme is worth an hour when relaxing on a quiet winter afternoon, as well as allowing my misunderstandings to be corrected. Public debate within organizations proved quite important to Lancaster University’s Department of Systems during its thirty-year research programme within real-world corporations: Soft Systems Methodology (SSM).

Relocated into university life from careers in the highly practical world of chemical engineering, department founders Professors Gwilym Jenkins and Peter Checkland aimed initially to assist industrial clients achieve corporate objectives, for instance, a more efficient distribution network for manufactured products. What evolved during Lancaster’s research into complex social scenarios, however, was a flexible and user-friendly means (SSM) to structure learning and debate among the concerned people taking part.

Rather than focus solely on quantitative problem-solving, Checkland devised the idea of ‘systems’ which were notional devices sketched on A3 paper as a practical means to stir discussion in situations holding opaque problems. These abstract ‘intellectual tools’ never pretended to represent part of the organization, i.e. how the world ‘is’. Rather, each was composed of English phrases (also known as ‘activities’) which in total made up a coherent whole for sharpening enquiry. Given SSM enquiries dipped into complex and ever-changing social circumstances, open debate proved invaluable to establishing a system’s relevance – it had to provoke meaningful debate among participants.

The theme ‘Return marked essays to students at appropriate time’ might appear as a diagram, whose logic included phrases such as ‘Define proper time’, ‘Obtain marked essays’ and ‘Deliver marked essays to students in correct time’. Participants may welcome this topic as important for their college, say, if they suspect an inordinate number of days are lost moving documents and marking according to painstakingly detailed schemes. Do tutors’ efforts justify outcomes? Could longstanding tradition welcome investigation by means of SSM-type diagrams, or is the institution a victim of top-down planning? Another example follows – the methodology is general purpose, not a set of principles reserved for educationalists.

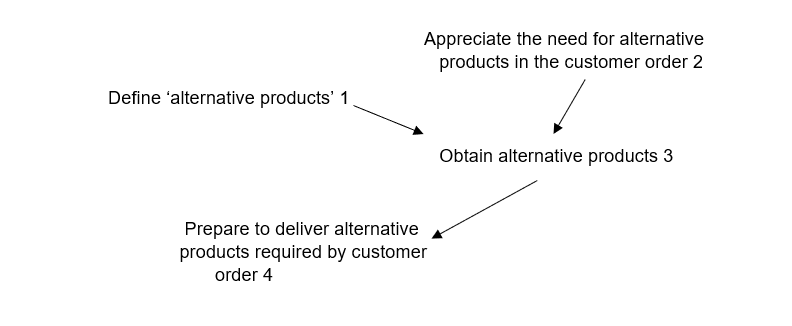

At major retailer DASA, Jo and her colleagues are pondering over an increasing number of returns: many customers don’t like items chosen by staff – which means restocking goods returned on DASA delivery vans. From the problem as so far understood, Jo sketches a notional system to assist delivery of orders by use of alternative products, substitutions necessary when customers’ choices are unavailable. The diagram is composed of seven activities; four are shown here, numbered, as usual, for the sake of easier discussion. Yet again, A3 flipcharts were vogue in this enquiry!

The diagram can be used in a general chat with employees, contrasting its logical arrangement with how things actually get done in DASA’s teams. Rational dependency is shown by arrows, as where activity 3 relies on input of information/resources from both activities 1 and 2. Regarding activity 3, the absence of, say, Dark Tray chocolates on warehouse shelf M74 and possible alternatives to Dark Tray (from activity 1) are both important. Does activity 1 need more attention, maybe additional internal product training for staff? That is for employees caught up in a particular culture to contest: methodology merely provides some structure to help investigate situations.

If any system fails to stir quality discussion it can be dropped from the enquiry, at best with responses about the diagram’s inadequacy used to steer learning and debate in new directions. Checkland’s neutral approach doesn’t assume agreement on cause-and-effect; SSM’s principles arrange purposeful talk by organizational members ensnared by hidden dilemmas, a subset of what was referred to as the ‘small, unrepeatable details of everyday life’. What Radio 4’s broadcast didn’t emphasize was the incredible number and variety of everyday life’s details, though to be fair to Berlin he does seem a modest chap, not like Tolstoy – ambitiously hoping to devise a system to explain everything.

Changes achieved when adapting SSM also tend to be modest: the problems under review, being political and opaque, may lack strong consensus even after two or three rounds of debate. Possible outcomes of this hypothetical DASA study include adjusting documents’ font sizes, the provision of warehouse layout diagrams for new recruits, or allowing staff more time to load their vehicles.

A little more radically, IT teams could get involved to consider the proposal of customers stating second-choices at home, typing orders via the company’s public website. In contrast with the well-tested search devices deployed by lay people nationwide in food and vehicle retailing, Peter Checkland’s ‘intellectual tools’ get proposed among small groups when organisational problems and desired outcomes are poorly understood. A bonus: you don’t need an Oxbridge background to participate.

By Neil Richardson, Kirkheaton

Responses