Could the solution to the Productivity Puzzle be Child’s Play?

Over the past decade, we’ve seen record levels of employment. But the amount each worker produces in the UK has hardly changed. Despite the improvements in technology, transport and knowledge, the dial showing output-per-UK-worker-hour has not budged. Until it does living standards for you and me won’t improve. In fact, it’s more puzzling because relative to other major economies, the UK has lagged behind.

Why?

Well, it’s hard to put your finger on exactly why and for that reason it is often described by economists and other worthy experts as a ‘conundrum’. There are lots of reasons they cite: lack of investment, lack of lending, labour ‘hoarding’…. I could go on. In the end, the only thing people agree on is that its complex, and solving it remains a puzzle. A big one. So, here’s a new suggestion: kids love puzzles. Why not ask them? Maybe they could solve it?

Productivity and the Skills Mismatch Problem

British businesses have been complaining for a number of years about a ‘skills mismatch’, that is, the new recruits coming into the world of work don’t have the ‘right’ skills for the jobs they take up. They aren’t ‘work ready’.

Even when they come ‘well equipped’, for example, with lots of academic qualifications, these aren’t the tools that are needed. According to UKCES (UK Commission for Employment and Skills), 25% of vacancies are not being filled because “companies can’t find the right people with the right skills”.

Some industries are more affected than others, one example being the digital arena, where businesses are struggling to maximise their potential as a result. A lot of this can be traced back to schools.

The CBI [Confederation of British Industry] have found that 69% of businesses are not confident that there will be enough people available in the future who are equipped to fill our high-skilled jobs.

Josh Hardie, CBI Deputy Director-General, attributed this shortfall to “the gap between education and the preparation people need for their future, as well as the gap between the skills needed and those people have”.

Noel Tagoe, executive director of CIMA Education says that the education system is “failing young people and failing business, because school doesn’t equip children with the basic numeracy and literacy skills on which to base a career”.

The knock-on effect of an under-skilled entry-level workforce can be seen when more than 90% of finance professionals surveyed in the UK reported that their workload had increased as a result of skills shortages, with 66% agreeing it had increased the stress levels of staff, and 44% that it had caused a fall in departmental performance.

In a nutshell: a lack of work-ready school leavers is undermining productivity in the economy, viz: the skills mismatch is dragging our economy down. So, if we agree on this much, why can we still not solve the problem?

Are we seeing Young People as the Problem rather than the Solution?

One of the main issues over the last few decades is that schools and colleges have focussed on churning out adequate exam results indiscriminately across the board. By pushing pupils to the holy grail of ‘going to university’, fulfilling the policy agenda set out in Tony Blair’s mantra of “Education, Education, Education”, this has created too much academic overload and related stress, as well as fear of failure associated with rising levels of emotional and psychological distress as an unintended consequence.

Michael Mercieca, CEO of Young Enterprise hits the nail on the head: “…exam results alone will not necessarily be enough to succeed in life. The education system must ensure that all young people across the country are prepared for the world of work.” The ASCL talks about young people needing a “mastery of new situations.”

To back this up the CBI survey found that employers rate attitude and aptitude for work as more important than academic achievement when recruiting school and college leavers. And, as we have seen, from the perspective of businesses whatever else our education system is doing, it isn’t helping us develop rounded individuals who can confidently and relatively easily adapt to the demands of today’s workplace.

The risk is that employers start seeing young people themselves as the problem, whereas here at Kloodle we see them as the potential solution. We believe that you can work with schoolchildren from an early age to develop and coach and help them to become more self-aware, fully ‘rounded’ individuals.

But to do this we will need to grasp another ‘productivity’ nettle: we must stop making ‘education, education, education’ mean ‘work, work, work’, as if exam results are a proxy for ‘school productivity’. Let’s face it, no-one wants to go to the pub with a nerd — except on quiz night!

So does Government now get this? Well yes, and no

The bit of the puzzle that government now clearly gets is all the stuff that businesses have been telling them above. We know this by looking at what they put in their new Careers Strategy published in December 2017: “We want all young people to understand the full range of opportunities available to them, to learn from employers about work and the skills that are valued in the workplace and to have first-hand experience of the workplace … This strategy will connect the worlds of education and employment”.

As well as a strategy, government has invested in the Careers and Enterprise Company (CEC). Through CEC it has now built a network of Enterprise Coordinators. Jobcentre Plus (JCP) advisers are going into schools to facilitate links with the local labour market. And, as we wrote about in a previous blog, the Gatsby benchmarks give schools and colleges a set of 8 quality standards to try to aim for in implementing a careers strategy within their own institutions.

Seven encounters from Year 7 is what the Government is proposing

By the end of 2020: “Schools should offer every young person seven encounters with employers — at least one each year from years 7 to 13 — with support from the CEC. Some of these encounters should be with STEM employers.” Perhaps most radically, government sees the success of its careers strategy as key to increased social mobility, something we care passionately about at Kloodle, too.

According to government “a modest increase in the UK’s social mobility to the average level across western Europe could be associated with an increase in annual GDP of approximately 2%: equivalent to £590 per person or £39 billion to the UK economy as a whole.”

So far, so good. But a number of questions remain unanswered. To be fair, policy makers acknowledge that evidence about what works is not yet there. And for one of its key ambitions — introducing careers education earlier across all primary schools — since its never really been done before, no one yet knows how to do it.

There is a £2 million programme to test approaches to careers guidance in primary schools. At Kloodle, we see this as an exciting new challenge. The reason we think this is because it is primary schools, in fact, that can open a path to social mobility.

How early is ‘early’? Some starting points for primary schools from what the research is telling us

Overall, although there hasn’t been a lot of research in this area, enough has been carried out to confirm the importance of careers education for young children, so that they can build awareness of different career paths, and why developing this awareness early on matters. At the same time, there are some risks involved in getting this wrong, which primary school leaders may need to think about.

Most recently in 2018, an international collaborative research study called “Drawing the Future” was completed.

Some of the key findings are worth looking at:

- The difference between children’s career aspirations from age seven to seventeen are marginal. Therefore, the conclusion is rather than leave the decision-making process until late teens, start the process early.

- Career decisions are often based on gender stereotypes, socio-economic backgrounds and influenced by TV, film and radio. This could explain why so few girls go into Stem-related careers, they just don’t think they belong there. There are few role models presented to help them believe it is a feasible option.

- Children’s career aspirations have little in common with projected workforce needs. These aspirations are heavily influenced by parents who promote careers which seemed important when they were younger; often they are out of touch and heavily biased.

The take-home messages here seem to be that unless we intervene earlier we just won’t make any impact on the kinds of issues that reinforce gender bias amongst young children and that limit their future career choices; or that result in whole areas of social disadvantage and ‘careers cold spots’, where lower levels of social capital produce lower levels of student aspiration and work attainment.

So, as well as connecting ‘the worlds of education and employment’ we need to reconsider at what age we start to make connections, and whether our current ‘decision-points’ are being set too late?

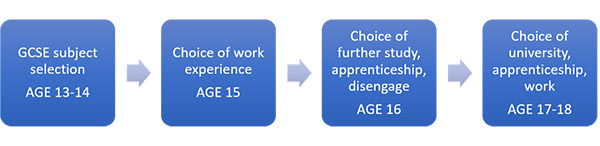

FIGURE 1 — A conventional ‘careers advice’ timeline with input post-13 but where factors that influence choices have been ‘pre-determined’ by experiences and influences that happen earlier?

How much is too much future-planning? Some possible problems with starting ‘too early’

One of the main concerns about bringing careers education into primary schools, though, is about the way it will be put into practice. Some of the research coming out of the ‘Nudge Unit’, for example, about ‘choice overload’ suggests we should pause for thought.

The Government is proposing to distribute factsheets, such as potential earnings based on historical figures, to guide young people with their career choices. But a fact-based approach relies on knowing which facts are salient today, as well as what those facts will look like tomorrow.

Putting young children under pressure to make choices affecting the rest of their lives may be setting them up to fail when no-one knows what the jobs market will look like in the next ten years. And providing static or ‘cold facts’ about jobs to young children today, when many jobs will have been changed irreversibly by technology by the time they are entering their careers is expecting them to make future decisions based on what will be ‘future-duff’ rather than ‘future-proof’ information.

Faced with these uncertainties there is a potential for ‘overload’: young children may find themselves overwhelmed by the number of careers and choices on offer and as a result can’t deal with the information and start to avoid these decisions altogether. Alternatively, if parental input is sought for consideration of a child’s future career prospects at an early age there is a risk of putting them under too much pressure with too many expectations.

Getting this wrong could exacerbate the mental health endemic affecting young people. You have academic overload, career choices overload, parental pressure overload. A very unhealthy cocktail.

Overload is unhealthy

Primary Profiles at Kloodle: it’s Child’s Play

The approach we are starting to explore with younger children at Kloodle is based on the kind of two-way relationship that we have found best connects the worlds of education and employment. We call it a Skills Based Approach to Primary Education. Crucially, based on what any primary school teacher or parent will tell you, young children aged 5–11 are not the same as young people aged 12–18, so the approach that we take needs to be different. For us, this is at an exploratory stage, so we are learning about what works from schools and pupils.

FIGURE 2: What our primary careers approach is starting to look like at Kloodle for ages 5–11

At Kloodle, we encourage young children to celebrate their successes and the skills they don’t realise they have. One method we find works really well is the badge system; children receive recognition for demonstrating their skills through the acquisition of digital badges. The more skills, the more badges and what comes with them is a real feelgood factor.

Historically, most schools and colleges which have used the Kloodle platform have introduced it to their Year 12 and 13 students. This is the time when schools need to make students start to think hard about their skillset and prepare for the world of work. However, we are now seeing a trend towards younger students commencing their journey and a number of schools and colleges have been requesting that students can activate their Kloodle profile from Year 7.

We would recommend this as it coincides with going to ‘Big’ school and, by building employability into the curriculum, it normalises the process. The exciting new challenge for everyone, and which we are starting to explore at Kloodle, is how best to begin to introduce the concepts of skills and skills development even earlier.

![]()

FIGURE 3: How our primary careers strategy feeds into an integrated process through the school journey

Starting at primary school would be the next logical step to embed employability into the curriculum as long as that part of the journey was carried out in a fun way to avoid stress. Kids love puzzles, and through building skills in Kloodle who knows, perhaps they could teach us something about how the world of work could become less stressful, more fun and … more productive?

Neil Wolstenholme, Chairman, Kloodle

If you are an employer and would like to get involved in work in primary schools with Kloodle then please email Phil Hayes, or if you are a primary school leader and think this might apply to you then please email Andrew Donnelly.

Responses