The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Employer Demand for Level 2-7 Apprenticeships

The past twelve months have seen an encouraging recovery for apprenticeships after the terrible impact that the pandemic’s lockdowns had on new starts on the programme.

From Recovery to Flatlining

According to the latest official data, the 328,800 starts for the first eleven months of the 2021/22 academic year were 10.2% higher than starts at the same point for 2020/21 and only 9.0% lower than the 361,400 reported at the same point for 2018/19 before coronavirus restrictions were introduced. Starts have been increasing at all levels and for all ages.

Another encouraging development is that while the Plan for Jobs employer incentives helped kickstart the recovery, their impact on starts has been minimal since January of this year and starts for young people and at the lower levels, where they initially made a big difference, have continued to grow.

But while there will be a lag between what is now happening and the publication of new data, warning signs suggest that starts may be about to flatline.

Falling Employer Demand Caused by Rising Business Costs

It is important to remember that apprenticeships are an employer demand-led programme. So perhaps it is more accurate to refer to the impact of increased business costs overall caused by rising inflation and the cost of borrowing.

Faced by these, one of the first things which employers look to cut is their bill for training, including apprenticeships. Training providers are reporting that planned apprenticeship recruitment is now being trimmed, even though we are still in the peak season for recruitment.

After scrambling to fill vacancies all year, employers are now experiencing a freeze in staff turnover. Businesses are keen to keep existing staff through, for example, offering household energy bill support and mental wellbeing support. Retail and hospitality employers are also having to support staff dealing with customers being abusive as they take out their frustrations at the rising cost of living. The cost of supporting staff alongside increasing wage costs inevitably has a knock-on effect on the budgets left for training.

Off-the-Job Training

A further concern in the current circumstances is whether employers can release apprentices to satisfy the off-the-job training requirements, especially in the run-up to Christmas. Programme completion rates are also suffering because some employers won’t put their apprentices through endpoint assessment once the apprentices have finished training. If an employer is unable to comply with the programme’s rules, then there is little point in committing to new recruits.

Potential Falling Demand by 16-24 Year-Olds

Demand from young people for an apprenticeship opportunity may also diminish.

As we saw in the pandemic, they might prefer to stay in full-time education or simply stay at home because they feel this offers them more security than a job during a downturn. The 174,000 16-to-24 year-olds who have started an apprenticeship this year is a large increase on last year, and they will have been attracted to the programme by the usual advantages of earning while learning and not being saddled with a huge amount of student debt. Therefore, it would be very disappointing if starts in this cohort fell back again.

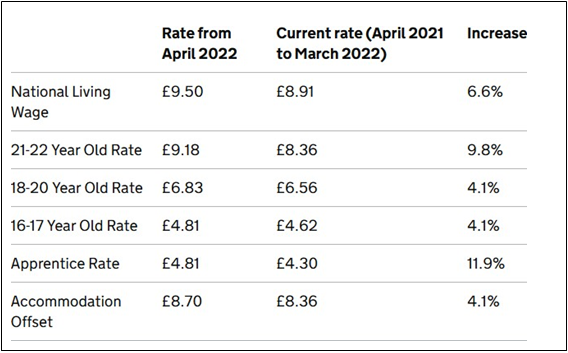

The critics of apprenticeships who claim that young people are exploited overstate their case, not least because many of them assume that the minimum ‘apprentice rate’ of pay (see Figure 1) is what all young apprentices are actually paid. The data published in the annual ‘National Minimum Wage: Low Pay Commission Report’ paints a very different picture.

It is true that for 16-to-18 year old apprentices, the median hourly rate is not significantly higher than the apprentice rate (estimates of £4.99 and £5.30 compared with the apprentice rate of £4.81), but the LPC figures show that for 19-to-20 year old apprentices, median pay tops £8 an hour in comparison with the national minimum wage of £6.83 for that age group. By age 23, the median apprentice wage is well above the national living wage.

Nevertheless, it is reasonable as many groups, including the British Chambers of Commerce, have said to the LPC, to ask whether scrapping the apprentice rate would make the programme more attractive to young people seeking employment. There is also a renewed worry that a recession may apply downward pressure on apprentices’ wages, while a Prince’s Trust survey has just found that nearly half (46%) of those aged 16 to 25 fear they won’t have money for essentials this winter.

For young people living at home (except in Wales), a parent is not eligible for child benefit for a child over 16 who is doing an apprenticeship. There are also work-related activity rules for claiming Universal Credit for those doing part-time apprenticeships under 30 hours a week. The last thing needed is a tilting of the system which results in parents discouraging their children from starting an apprenticeship.

Independent Training Providers

In good times and bad, it is training providers who keep the wheels of the apprenticeship programme turning and just like other businesses, they are facing enormous challenges in the current crisis. Virtually no funding rates for apprenticeship standards to cover the costs of the training and assessment have increased since 2017 and it is a dereliction of duty on the part of the Government that it has been so slow to address this. The longer the neglect, the more danger the provision at lower levels will be in because many programmes will simply not be sustainable.If media reports are accurate about the new Government’s attitude towards immigration, perhaps ministers don’t particularly care whether apprenticeships and other types of skills training are a solution to filling Britain’s skills shortages. The Home Office is apparently willing to train employers to take advantage of a more relaxed visa system, which means that there will be less incentive for employers to invest in training.

Recommendation 1

The Government should review how the levy collected from employers in England is distributed via the Apprenticeship Programme Budget, ensuring that funding remains focused on apprenticeships-only but increases access to 16-24 year-olds, small and medium-sized enterprises and apprenticeships at Level 2 and 3 as well as Level 4 and above.

Recommendation 2

DfE, ESFA and IfATE should recognise that the number of apprenticeships and especially the quality of programmes will only be preserved if an uplift is applied to the funding rates of many standards at the lower levels.

Recommendation 3

The Government should accept that the ‘apprentice rate’ for wages has become an unwelcome distraction. It should be abolished. The existing structure of the minimum wage should apply to apprentices and any uprating or restructuring in the future.

By Aidan Relf, Skills Consultant

This article is part of Campaign for Learning’s series: Learning in the cold: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Post-16 Education and Skills

Order of series

Day 1

Friday 21st October

- Louise Murphy, Economist, Resolution Foundation: The Cost-of-Living and the Energy Crisis for Households

- James Kewin, Deputy Chief Executive, Sixth Form Colleges Association: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and 16-19 Year-Olds in Full-Time Further Education

Day 2

Saturday 22nd October

- Becci Newton, Public Policy Research Director, Institute for Employment Studies: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and 16-18 Year-Olds in Jobs with Apprenticeships

- Zach Wilson, Senior Analysis Officer and Andrea Barry, Analysis Manager, Youth Futures Foundation: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and 16-24 Year-Olds ‘Not in Full-Time Education’

Day 3

Monday 24th October

- Nick Hillman, Director, Higher Education Policy Institute: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Full-Time and Postgraduate Higher Education

- Liz Marr, Pro-Vice Chancellor – Students, The Open University: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Part-Time Higher Education in England

Day 4

Tuesday 25th October

- Steve Hewitt, Further Education Consultant: The Cost-of-Living Crisis: Access to HE and Foundation Year Programmes

- Sophia Warren, Senior Policy Analyst, Policy in Practice: The Cost-of-Living Crisis, Universal Credit, Jobs and Skills Training

Day 5

Wednesday 26th October

- Paul Bivand, Independent Labour Market Analyst: Economic Inactivity by the Over 50s, the Cost-of-Living Crisis and Adult Training

- Aidan Relf, Skills Consultant: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Employer Demand for Level 2-7 Apprenticeships

Day 6

Thursday 27th October

- Mandy Crawford-Lee, Chief Executive, UVAC: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Employer Demand for Level 4+ Apprenticeships and Part-Time Technical Education

- Simon Parkinson, Chief Executive, WEA: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Adult Community Learning

Day 7

Friday 28th October

- David Hughes, Chief Executive, AoC: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and FE Colleges

- Jane Hickie, Chief Executive, AELP: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Independent Training Providers

Day 8

Saturday 29th October

- Susan Pember, Policy Director, HOLEX: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Adult Education Providers

- Martin Jones, Vice-Chancellor and David Etherington, Professor of Local and Regional Economic Development, Staffordshire University: The Cost-of-Living Crisis – The Response of Staffordshire University

- Chris Hale, Policy Director, Universities UK: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Universities

Responses