The Cost-of-Living Crisis and 16-18 Year-Olds in Jobs with Apprenticeships

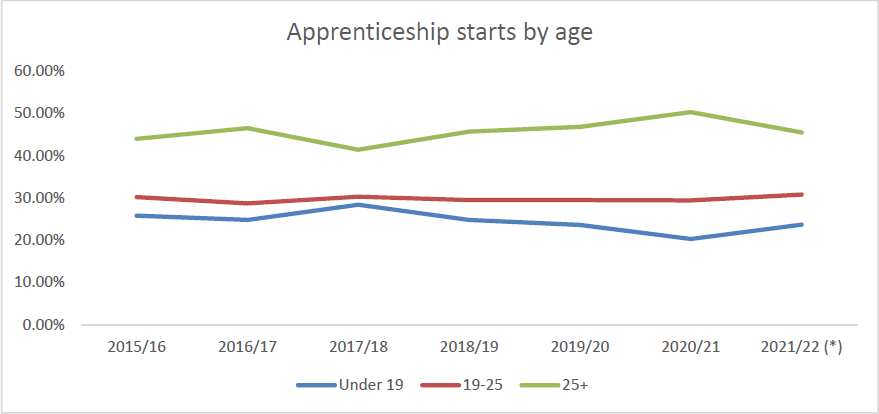

According to the latest data , 16-18 year-olds form 23.7% of the apprentice population. As Figure 1 illustrates, over time, their proportion had declined substantially so this is an improvement with 68,500 now involved. However, the published data allows us to know relatively little about this group particularly on the intersections between demographic factors, uptake and completion, and crucially, on individual economic contexts.

(* covering three-quarters of the academic year)

Future Earnings

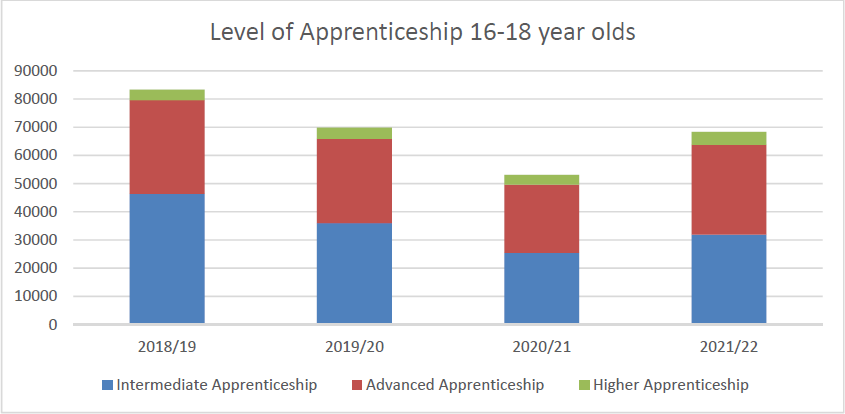

The latest data contains a promising sign for longer-term financial gains for young people and the economy (Figure 2). Whilst training at Intermediate level (Level 2) was previously most common for 16-18 year olds, in 2020/21 there is a balance between training at Intermediate and Advanced levels (with close to 32,000 in each), so more 16-18 year-olds are now training at Level 3. If completed, CVER estimates 9% wage returns on average to apprenticeships at Advanced level, and achieving Level 2 predicts much better economic and social outcomes than not doing so.

Current Pay

We should also consider the pay that young apprentices attract; it is a key reason for young people to question whether apprenticeships are a good quality opportunity .

Hourly apprenticeship national minimum wage (ANMW) is £4.81, up from £4.30 in 2021, as it was reviewed and uprated due to a finding by the Low Pay Commission (LPC) that it “did not ensure a decent standard of living for young people; left them struggling to cover basic living costs; and could cause hardship and distress”.

An apprentice can be paid the ANMW through to their 19th birthday whereas an NMW employee will see a raise to £6.83 on turning 18. The 2022 ANMW is an improvement; in 2021, it was 32p less than the minimum wage rate for 16-17 year-olds. However, in the current context it may not be enough. Of apprenticeship vacancies, 40% are advertised at ANMW but employers can pay more. The median gross hourly pay for 16-18s is £6.58, which suggests a median monthly pay of around £958 including paid off-the-job training, when using an assumption of a UK working week average of 36.4 hours.

However, LPC indicates the “fall in the number of apprentices doing lower-level apprenticeships has driven growth in median pay” – hence, young people in Intermediate level apprenticeships may be most at risk. For these individuals, monthly wage could be around £700 although those who are care-experienced may attract a one-off payment of

£1,000 in maintenance costs. However, the LPC records high levels of underpayment of the off-the-job training so monthly pay could be 20% less, and therefore closer to £560.

Impact of the Cost-of-Living Crisis

The current minimum wage rates are reproduced in Figure 3. The Low Pay Commission is considering the rates and structure of the minimum wage from April 2023.

In the context of the cost-of-living crisis, however, the Living Wage Foundation has increased its assessment of the basic income people need to ‘get by’ in the UK to £10.90 per hour (£11.95 in London). But as of yet, changes to NMW and national living wage rates have not been announced, and so a basic calculation indicates the ANMW is £6.09 adrift from a rate necessary to ‘get by’.

Whether this pay rate is adequate depends on the circumstances of 16-18 year-old apprentices, and specifically the difference their pay makes to their household.

For young apprentices in middle or high-income households who are supported by their family and are using their wage for their own lifestyles rather than as money their household relies upon, the implications of the inflationary economy may be manageable.

In contrast, young people in low-income households are seeing the value of their contribution to household income decline and travel and subsistence costs rise, and those attempting to live independently or building their own families on the ANMW, will struggle.

Entering Higher Paid Non-Apprenticeship Jobs

The risk is the creation of perverse short-term incentives with long-term consequences. The ability to attract a higher wage rate in a non-apprenticeship job on turning 18 – in a tight labour market – may encourage young people to drop-out of apprenticeships to access better paid work short-term. Longer-term, not achieving a Level 2 or 3 has consequences for wages, progression, and health and wellbeing as well as the economy. Completion rates are already weak – as such, we need to turn that around by improving ‘the offer’ to young people.

Recommendation 1

ONS and DfE should develop and publish data which identifies whether 16-18 year-olds in jobs with apprenticeships are living independently or with parents, and extend the 16-19 Bursary Grant to apprentices from poorer households accordingly.

Recommendation 2

HMRC should ensure greater compliance of employers, paying the relevant minimum wage rate to 16-18 year-olds on apprenticeships and seeking to recoup underpayments from offending employers.

Recommendation 3

18 year-olds on apprenticeships should be entitled to the current employed 18-20 year-old rate of £6.83 from day one of starting their apprenticeship.

By Becci Newton, Public Policy Research Director, Institute for Employment Studies

This article is part of Campaign for Learning’s series: Learning in the cold: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Post-16 Education and Skills

Order of series

Day 1

Friday 21st October

- Louise Murphy, Economist, Resolution Foundation: The Cost-of-Living and the Energy Crisis for Households

- James Kewin, Deputy Chief Executive, Sixth Form Colleges Association: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and 16-19 Year-Olds in Full-Time Further Education

Day 2

Saturday 22nd October

- Becci Newton, Public Policy Research Director, Institute for Employment Studies: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and 16-18 Year-Olds in Jobs with Apprenticeships

- Zach Wilson, Senior Analysis Officer and Andrea Barry, Analysis Manager, Youth Futures Foundation: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and 16-24 Year-Olds ‘Not in Full-Time Education’

Day 3

Monday 24th October

- Nick Hillman, Director, Higher Education Policy Institute: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Full-Time and Postgraduate Higher Education

- Liz Marr, Pro-Vice Chancellor – Students, The Open University: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Part-Time Higher Education in England

Day 4

Tuesday 25th October

- Steve Hewitt, Further Education Consultant: The Cost-of-Living Crisis: Access to HE and Foundation Year Programmes

- Sophia Warren, Senior Policy Analyst, Policy in Practice: The Cost-of-Living Crisis, Universal Credit, Jobs and Skills Training

Day 5

Wednesday 26th October

- Paul Bivand, Independent Labour Market Analyst: Economic Inactivity by the Over 50s, the Cost-of-Living Crisis and Adult Training

- Aidan Relf, Skills Consultant: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Employer Demand for Level 2-7 Apprenticeships

Day 6

Thursday 27th October

- Mandy Crawford-Lee, Chief Executive, UVAC: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Employer Demand for Level 4+ Apprenticeships and Part-Time Technical Education

- Simon Parkinson, Chief Executive, WEA: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Adult Community Learning

Day 7

Friday 28th October

- David Hughes, Chief Executive, AoC: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and FE Colleges

- Jane Hickie, Chief Executive, AELP: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Independent Training Providers

Day 8

Saturday 29th October

- Susan Pember, Policy Director, HOLEX: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Adult Education Providers

- Martin Jones, Vice-Chancellor and David Etherington, Professor of Local and Regional Economic Development, Staffordshire University: The Cost-of-Living Crisis – The Response of Staffordshire University

- Chris Hale, Policy Director, Universities UK: The Cost-of-Living Crisis and Universities

Responses