What happened to youth apprenticeships?

Half a century ago around one third of teenage boys entered apprenticeships on leaving school, mostly into programmes of 3-4 years in manual trades. A sizeable – though much smaller – proportion of girls also entered apprenticeships in fields like hairdressing. These apprenticeships provided many young people with a route into stable and secure employment.

Fast-forward to the present day and less than 1 in 20 young people between the ages of 16 and 18 are apprentices, while more than half of all apprentices are over the age of 25. Apprenticeship programmes have become very diverse, now covering a much wider range of occupations, educational levels and programme lengths including many shorter programmes between one and two years in length. Slightly more than half of starting apprentices are women.

As a result, apprenticeships in England are very different to those offered in the past and also those in other countries. In most of continental Europe, apprenticeships remain primarily part of the upper secondary education system, serving young people rather than adults, and with programmes at least two years in length and often four.

The decline in young apprentices

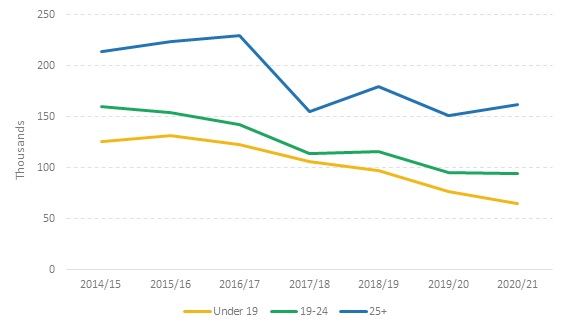

While the increasing scope of apprenticeships has advantages, a key question is whether the system still provides young school-leavers with a route to a good job and rewarding career. Apprentice starts among those under 19 nearly halved from around 120 thousand in 2014/15 to just over 65 thousand in 2020/21.

The number of apprenticeship starts in England by age group

These falling numbers matter because apprenticeships can help young people into good jobs. A recent study shows that starting an apprenticeship at Level 2 or 3 is associated with higher average returns than completing classroom-based vocational qualifications at the same level. For men, apprenticeships raise earnings by 30% and 46% for those educated up to Levels 2 and 3 respectively, relative to a classroom-based vocational qualification at the same level. For women, they raise earnings by 10% to 20% for the respective groups.

What are the obstacles to youth apprenticeships?

Several factors discourage youth apprenticeships, both on the side of employers and for young people. For those with the weakest school attainment who are not able to immediately begin an apprenticeship, the routes into apprenticeships, such as traineeships, are more limited and less well-funded than in many European countries. For example, in Germany there is a well-established transition system which enables those with weak school attainment to access apprenticeships, while in Austria the state-funded ‘shadow’ apprenticeship programme serves a similar function.

In England, some key minimum regulations governing apprenticeships are inadequately enforced. According to a recent government survey, more than half of apprentices were not receiving the mandated off the job training entitlement. The Low Pay Commission reports that apprentices are more than ten times more likely than an average worker to get less than the legal minimum wage.

Funding factors are also critical. Since the introduction of the Apprenticeship Levy in 2017, large employers must contribute 0.5% of the part of their pay bill over £3 million as an apprenticeship levy. The levy has altered both the type of firms offering apprenticeships, and the type of apprenticeships offered. Apprenticeships at advanced and higher levels have grown fast, and these are usually targeted at older individuals.

Fixing the apprenticeship system

Most of us accept the need for solid quality alternatives to the well-worn path from GCSE to A level to university. Although T Levels are part of the answer, their rollout is still limited and they do not offer the kind of intensive work-based learning offered by apprenticeships. A series of recent reports have therefore underlined the importance of more and better youth apprenticeships. The challenge is how to realise this shared objective. So, some suggestions:

First, enforce the existing (good!) regulations on training and wages. These regulations ensure that apprenticeships are an attractive option and provide the development opportunities that young people need.

Second, the current funding system is squeezing out youth apprenticeships. Within the levy framework, funding for youth apprenticeships needs to be ring-fenced and reinforced. This will involve offering incentives for employers to offer apprenticeships to young school-leavers.

Third, we need, like many other countries, to develop a more effective safety net of programmes for those with the weakest GCSE attainment. This group may find it difficult to enter an apprenticeship immediately, but the aim would be to support their transition into apprenticeships. This could build on existing traineeships through better funding, and a clear route into quality apprenticeships.

In the past couple of decades, England’s apprenticeship system has become broader in scope with many older learners becoming apprentices. Although this new system has advantages, it seems to have come at the expense of young apprentices for whom apprenticeships often provided a route into employment. Young school leavers need, and deserve a revived youth apprenticeship system.

AND

Responses