The End Of The Class System: Is It Time For A New Beginning?

The Series: This is the last article of a four-part series on university grade inflation; we’ve explored the incontrovertible evidence, the underlying causes, the defence by universities and the possible ways to resolve the problem.

This one is about the defence by universities.

Dear, Oh Dearing!

The Dearing Report in 1997 on the future of higher education insisted that “students and employers must be able to rely on the value, quality and standards of qualifications.”

….students and employers…

From that time in ‘97, the link between education and employment became embedded as the Government messaged that university was less about academia and more about getting a job; so that the cost of education had the tangible benefit of producing a ‘skilled workforce’ for the service economy.

These were the days of no or low fees, so it was a bit of a no-brainer that, if you could get into university, you were more likely to get a good job by taking advantage of the graduate premium. Fast forwarding, the numbers of UK students going to university has almost doubled since 1998.

…..Value, quality and standards…

With so many good degrees flooding the market, the value of a university education in terms of employability has diminished. The two key ingredients which have fuelled the explosive inflation are the cocktail of university autonomy and the introduction of course fees:

- Conflict of Interests: one of the advantages universities enjoy is autonomy to set their own curricula, own grading system, own algorithms, own selection of courses and teaching, marking and moderation, free from regulation and interference from outside.

However, and here’s the rub, they then benefit from the high grades this degree factory churns out;

It’s called a conflict of interests.

With no gamekeeper, autonomy has led to raging grade inflation, which even the Government has admitted is artificially high and unjustified. Unless this inflation rate abates, and that looks unlikely, then it will lead to the ‘dangerous impression of slipping standards’ and unfortunately the only solution will be interference and ultimately self-abolition. Recognising the problem, the inevitably toothless Office for Students has been set up to deal with the issue, but it doesn’t have the rule of law; it writes reports and wags fingers.

- Introduction of fees: ‘a shift towards consumerism’ had meant that universities’ marketing departments are focussed on the KPI of satisfying the value for money quest of their clientele, who are customers not students anymore. Competition, which in free markets would usually be encouraged to keep fees down and improve quality, has created a bubble which, in this situation, pushes grades up. Fees should reflect potential outcomes. Lower fees at some institutions could result in the market being flooded with cheap degrees, but at least people would know what they are paying for. Maybe franchising of the best universities is the way to go.

It has also resulted in a proliferation of different degree courses; around 65,000, at 200ish providers. All of this choice makes comparability and selection of courses complicated for students, and, likewise, it’s hard for employers to distinguish on a qualifications’ basis between candidates with so many good degrees on offer. And once choices become difficult then many employers revert to other methods, like internal assessment tests or even nepotism, which slants the playing field.

The reliability that Dearing demanded is now in jeopardy.

There is massive inconsistency in standards between institutions and the only way to resolve this and improve transparency is to have a national set of standards and an independent assessment body, like A levels. Then we’d see a better comparison across universities. If the corporate world is to be the beneficiary of these qualifications, then shouldn’t employers be involved in the output? How would that work?

What Are Consequences of Grade Inflation?:

1. The Future is Unknown, But the Debt is Certain

For students, I just don’t think the debt-for-life reality has sunk in yet. Or they haven’t been spoon-fed the right information on which to base decisions. And their colleges and parents are pushing them to ‘live the dream’ that they believe will lead to enhanced earnings and a better life.

A number of studies determine that the net present value of going to university overall is positive, BUT, this is based on ‘facts’ as we see the world today and with hindsight. Over the next 20 years, many jobs and careers will fade away and unforeseen ones will spring up. The calculations are flawed. Forty years ago, no-one said go into tech; there wasn’t any!

Also, the statistics are based on a graduate population en masse, some of whom will do spectacularly well financially, becoming CEOs etc., skewing the figures as a result. This is the ‘it could be me’ siren call of the lotto, luring young people in, just to dash their aspirations on the rocks of debt if the qualification leads nowhere. Because of the fees, students are more likely to apply to courses where they think there’ll be some employability outcome, such as business studies. More sobering data reflects the mismatch between education and employment: that nearly half of employed recent graduates are working in non-graduate roles. Also, over 40% of graduates overall work in the public administration, education and health industry. Their salaries won’t be shooting the lights out. According to The Sutton Trust, 81% of student debt will never be repaid, suggesting fees are way too high.

2. Social Mobility Inhibited

By having the same fees across the board, it creates the impression of the same product, just at different locations; this is a false and misleading market. Although you could argue that it is worth paying the cost of a degree from a top university, young people from less privileged backgrounds are generally less likely to gain access to the more prestigious universities. So, many students will study at the local uni, stay at home to save costs, commute to the local town, encounter little diversity, have a narrower network and, in doing so, will not embrace the full uni experience, ending up trapped paying down a huge amount of ever-growing debt. You might get a good degree, but so does everyone else.

3. Can’t Get A Job, Do A Masters

The Institute of Directors claims: “Business leaders have increasingly looked at extra-curricular achievements to differentiate between graduates, and grade inflation may have contributed to this trend.” As a result, many more graduates are going down the masters or PhD route to differentiate themselves. Latest stats show that a post grad degree can seem worth it as there appears to be an earnings premium and good employment prospects. Student numbers on masters’ courses in the UK have increased by almost 50% since 2008 and, post-Covid, it’s going to accelerate.

But it means another year of not earning, another year of racking up debt and more and more applicants with the new currency of a masters. The US is an indicator of the future direction of travel for the UK; there the masters route, particularly in business, is a well-trodden path with an earnings bump expectation, resulting in 9% of the population now having a masters’ degree!

4. Graduates Are Not Oven Ready Employees

Good degree results do not reflect potential suitability or success in the world of work today.

This is straight from former Secretary of State for Education Gavin Williamson’s mouth:

“And employers say that too often, graduates don’t have the skills they need, whether that’s practical know-how or basic numeracy and literacy.”

Good degrees, yet poor employability skills?

Historian Geoffrey Alderman sums it up nicely:

“But what do all these “classes” mean? In my experience they mean very little. The historic emphasis in British universities on performance in a set of written examinations has generally meant that firsts are awarded to those who perform best (whatever that means) under exam conditions.

“The problem is, life is not lived under exam conditions.”

And that’s it in a nutshell: The academic route was never designed for employment.

Back To The Start

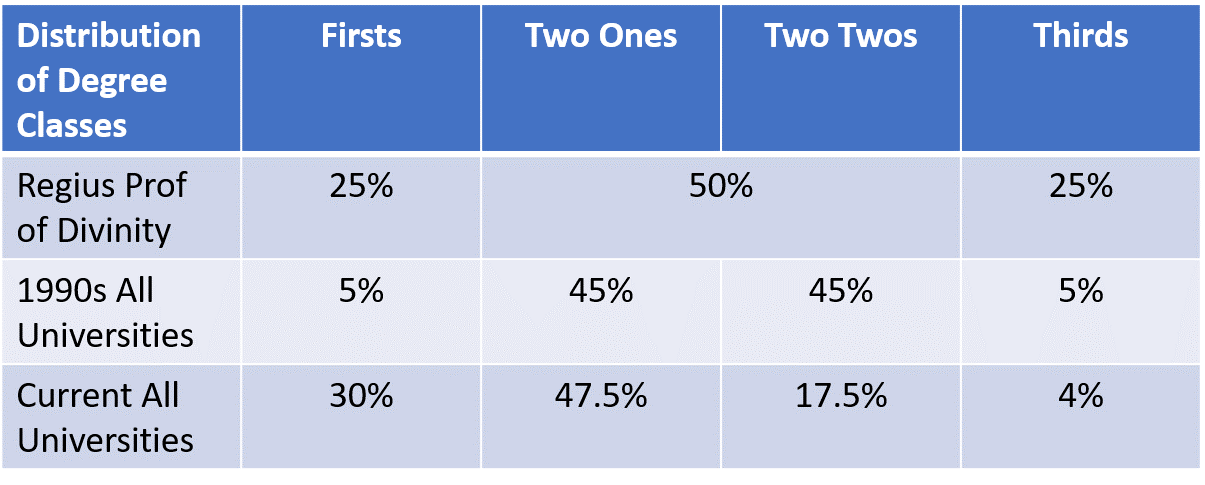

The degree classification system is antiquated; the original organisation of the students’ results into three broad categories of 25%, 50%, 25% was devised in the 16th Century in Cambridge by the Regius Professor of Divinity as a way of distinguishing performance. Divinity is a pretty niche subject these days, but the principle of effectively placing students into evenly distributed quartiles makes sense.

No-one needs an explanation that these quartiles represent; good pass, just pass, marginal fail, proper fail. But the terminology adopted came from an age when the societal class system reigned and the jargon reflected that.

Up until the 1990s, the distribution of firsts to thirds was broadly split 5%, 45%, 45%, 5%, which perhaps clumped too many graduates in the middle, with the exceptional at either end.

The current distribution across the board is 30%, 47.5%, 17.5%, 4%, which is very skewed.

The time is ripe for consolidation, rebranding and reduction in the academic industry.

Press The ‘Reset’ Button

When I lived in Brazil, inflation was rampant, reaching 2,000% per year at its peak. The Brazilian people and Government lived with it until it got out of control then, in a panic, they would press the ‘reset’ button; this involved changing the currency overnight and pegging to something external, reliable and solid…in this case, the dollar.

University education needs to be reset. Government interference is inevitable.

There are a few extreme possibilities. One basic ‘no frills’ option is what they do in medicine, where there is no degree classification (it’s too risky to advertise ‘good’ doctors and bad ones), just pass or fail. It’s all about the end game of becoming a doctor. This one is too binary and needs more colour.

The other extreme is witnessed in dentistry, where every student in the country is put into a ‘name and shame’ order from best to worst. Easily comparable courses across universities helps but, yikes, more painful than wisdom teeth if you’re near the bottom. Good idea, but too many mental health issues! This method could only be implemented if the vast numbers of courses were rationalised into broad categories, which, I believe, should be done anyway.

The Think Tank, Reform, is suggesting something similar to the Regius Professor method along the lines of a fixed 10:40:40:10 split.

This structure is a bit more than just pass or fail and akin to the professional exams, such as the accountancy, where they work on the basis of set numbers of students passing and failing, right across the country, in order to preserve standards (if only!).

In the US, concepts of charging for education and expecting value for money are entrenched. There, students receive a specific score, the GPA, and a transcript on graduation, detailing the courses studied and grades achieved with explanation, which is more VFM than a mere certificate. It’s very clear and transparent; 3.6 is better than 3.2, can’t argue with that. But this is no guarantee against inflation, it just increases transparency. For VFM’s sake, let’s do the transcript.

More Flexibility Please

The first thing to change must be the timeframe and the culture. The concept of Lifelong Learning means that you don’t have to ‘play your joker’ too early, so the traditional three-years’ course could be reduced to two or even one. Broader courses based on key numerical, computer, oral and written skills with shorter holidays and online modules would be more useful for getting ready for employment; is that the end-game? In future, people will have to get used to the idea of having five or six careers during their lifetime, so being nimble and knowing how to retrain will be essential. It will be skills, such as resilience and communication, which probably hold you in better stead rather than technical information.

So, fixed grade distribution, tougher regulator, new grade names, franchises, national standards, lower fees, shorter courses, lifelong learning, specific marks, a nice transcript to post on your Insta-page. That’s what the new academic system should look like.

Viable Alternatives To Fill The Void

The pure ‘academic’ route doesn’t have to be for everyone. In fact, it’s the failing of having credible, well-publicised alternatives which is the reason why so many young people believe university is the route to employment. Investment in higher apprenticeships and degree apprenticeships which combine classroom learning with on the job experience is essential. The key is that the course fees are covered by the employers. The advent of T levels demonstrates that the Government is finally focussed on offering a strong technical route to employment at an early stage, and “minimising the number of people entering the labour market without useful skills and qualifications.”

The demise of the degree class system is nigh.

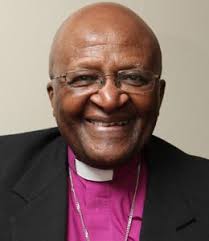

And as the legendary classification eponym Desmond Tutu makes his exit, the Government should heed his parting shot: “Forgiveness says you are given another chance to make a new beginning.”

Neil Wolstenholme, Chairman, Kloodle

Responses