Black FE Leadership Group: If not us, who? If not now, when?

As a member of the recently formed Black @FELeadership Group (BFELG), I am hugely encouraged by the response to and engagement with our Open Letter since its circulation last month.

For the record, we have received over 200 expressions of support to the letter from individuals and organisations keen to discuss ways we can work together to address the challenges associated with systemic racism in FE. Responses have come from black and white leaders and staff active within the sector, alongside a range of eminent supporters and allies.

In addition, constructive discussions have taken place with the Association of Colleges (AoC), the Education and Training Foundation (ETF), recruitment companies and other key national and regional membership networks. As part of our initial engagements, we have been particularly struck by the universal commitment of these organisations to engage with BFELG’s ‘10 Point Plan’, and action plans are beginning to shape up.

Early indications are that a number of college senior leadership teams and their boards are also looking at how they can implement the ‘10 Point Plan’ internally, using it as a ‘Toolkit’ for bringing about real and sustainable change across their institutions.

We are due to meet more key stakeholders and potential partners in the coming weeks, which will further help to shape our and their thinking. Furthermore, we are committed to collaborating across traditional educational boundaries and across sectors such as schools, universities, health, policing, etc.

Silence from the “machinery of government”

Significantly and disappointingly, we have not yet received a response from the Government and its key departments and agencies representing the “machinery of government”.

This is particularly concerning in the light of the imminent prospect of the withdrawal of government funding for the annual collection of workforce data for the FE sector. The recent release of the FE Workforce Data for England (Analysis of the 2018/19 Staff Individualised Record (SIR 27) illustrates the reason why government support and engagement is critical.

Within the limitations of the latest Survey’s dataset, which reflects records for just under 50% of the total FE workforce of 216,000 staff, the SIR 27 Report (June 2020) shows that the FE workforce comprises: 80-90% white British across all provider types, followed by White Other”, “Asian (excl. Chinese”) and “Black” as the next largest categories.

When we look further into the ethnicity split in the FE workforce by excluding white British staff, this shows that – of the relatively small number of non-white British staff – “White Other” is the largest ethnicity in colleges, local authorities, and independent providers. The data shows an overall decrease in the “Black” and “Other” ethnicities.

Similarly, the ethnicity distribution for those in leadership positions (i.e. middle managers and senior managers) shows that there is an overall increase in white British middle managers over time, from 86% in SIR 21 to 88% in SIR 27. During the same period, there are corresponding decreases in “Black”, “Asian” and “Other” ethnicities.

The overall “Black” and “Asian” representation in senior leadership positions have consistently decreased over the lifetime of the SIR Survey from 2012/13 (SIR 21) to 2018/19 (SIR 27). No data is collated for ethnic representation on FE providers’ boards.

When we consider that the BAME student participation across FE approximates to around 30% of the total student population, and the fact that almost all of the sector’s national regulatory and representative organisations comprise 100% White British senior leadership teams, you start to gauge the extent of the issues that prevail in FE.

Within this context, passivity is no longer acceptable.

A personal request to the ‘Guardians of Further Education’

With this in mind, I have revived a personal request I made to the ‘Guardians of Further Education’ almost two years ago:

Dear Colleague,

On the occasion of the centenary of the armistice, we all owe it to those who came before us, not to forsake what they fought for, and to honour the values that have enabled us to prosper. Further Education has always been the embodiment of the principles of inclusion, tolerance and social justice, and I am indebted for the opportunities it has afforded to me.

So, in the spirit of armistice, this is a very personal appeal to ask the ‘Guardians of FE’ to uphold the principles on which it is founded. Failure to do so will do irreparable damage to the communities it seeks to enable.

In the run-up to events marking this special armistice, a statue of a Sikh Soldier, entitled ‘Lions of the Great War’ was unveiled in the town of my upbringing, Smethwick, in the West Midlands. More than 1 million Indians served in the British Indian army during World War 1, the largest volunteer army of the Great War. Whilst Sikhs made up 1% of the population of The Raj at that time, they comprised 22% of the British Indian Army during WW1.

The following excerpt from an article published in The Guardian on 12th November 1914, struck a particular cord:

“It was a curious sight to all of us, French or English, the day the Indians arrived in a dreary little town of Northern France…..a regiment of Sikhs, walking at a brisk pace, all big and strong men, with curled beards and the wide ‘pagri’ round their ears….they looked all like kings.”

My father was ‘bestowed’ UK citizenship, by virtue of his service in the British Police Force, based in Singapore. However, alongside many people who arrived in Britain in the 50s, he soon discovered life to be less than benevolent. He gained employment in the metal-bashing industries of Derby and the Black Country. In the early years, he lodged with eleven other men, operating a daily “six-on, six-off” shift rota.

Like Frank Skinner’s father, dad worked a six-day week in the Birmid Foundry near West Bromwich, clocking off at Saturday lunchtime to work off his thirst at the Red Cow pub and ending the day watching professional wrestling on the TV. Mum joined dad, from Punjab, four years after his arrival; later working on the production line at Tube Products, producing bicycle frames for Raleigh.

When I entered the world, my parents had settled in Smethwick, just as it became the epicentre of the most racist election campaign ever fought in Britain.

In the 1964 general election, the Tories took the Smethwick seat on a 7.2% swing. The local campaign focused on a backdrop of factory closures and a growing waiting list for council housing, adopting the slogan “if you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour.”

Extremists encouraged by history, 8 years after the Great War, Oswald Mosley (creator of the British Union of Fascists) had been elected as Smethwick’s MP, formed a British branch of the Ku Klux Klan.

Smethwick’s ethnic minority residents, including my parents, had burning crosses put through their letterboxes.

A year after the election, Malcolm X visited Smethwick, invited by the Indian Workers’ Association, of which dad was a paid member. He led the ‘Marshall Street Protest’ against an official policy of racial segregation in the town’s housing allocation.

Anxieties were further heightened by Enoch Powell, the Tory MP for nearby Wolverhampton South West, who delivered his notorious “rivers of blood” speech in Birmingham in 1968, just four miles from Smethwick.

Alongside their compatriots, neighbours and friends, my parents genuinely feared for their own futures, their children’s futures and that of their community.

The threat of repatriation was real; unconsciously transmitted to us through coded discourse at the supper table, discarded racist literature and unsealed envelopes in the bread bin containing funds to be sent back to the Punjab.

What sustained the town during this traumatic period was a sense of agency – a common purpose that mobilised the predominantly White British, Afro-Caribbean and Punjabi working-class population against outside provocation. The values of fairness, concern for others and social justice unified families, and helped to harness a safe, happy and integrated upbringing for their children.

For many of us, education was the key enabler.

During the 70s and 80s, the local schools, colleges and universities were mandated to work together to develop empathy, hope and ambition amongst the town’s young people. I completed A levels at Smethwick’s Chance Campus (then part of Warley College now Sandwell College), and became the first family member to progress to Higher Education. My two brothers followed similar routes, thereafter.

As a result, the notion of fear largely dissipated from our lives.

I am eternally grateful that further education afforded me the privilege to facilitate the learning of tens of thousands of learners and enable diverse communities across England. Due to FE, I became the first person from a black and minority ethnic background to hold the post of principal in a large general FE college in London. Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College became a ‘Beacon College’ during my time there. I returned to my roots at Walsall College and elevated it towards becoming the outstanding college it is now, which subsequently raised the bar amongst Black Country colleges. I collected the Queen’s Anniversary Prize from Her Majesty Elizabeth II on behalf of Cornwall College, the only institution in the Duchy to ever have received this award.

I am particularly proud that, in my final year in FE, my College’s teaching and learning was judged as “good across the full range of campuses, community venues and on employers’ premises”, and our curriculum described as a “catalyst for raising skills of the local workforce”.

Just days before Armistice Day, the Lions of the Great War monument was defaced. Graffiti left on the statue implied the same divisive messages, the people of town witnessed half a century before. For those Sikh soldiers, my parents and me too, the cycle of being celebrated, victimised and demonised is all too familiar.

My lived experiences mirror those of the current generation of black students and staff within the FE sector. The FE system’s propensity to allow race inequalities to persist, fester and threaten the very communities we all purport to represent is untenable. Apart from affecting the esteem of students, curtailing the careers of staff and diminishing the reputation of local institutions, it perpetrates a climate of fear. Fear is the antithesis of shared learning. Rather than engendering inclusion, collaboration and trust, it threatens the very sense of agency, communities expect us to role model.

Sadly, this type of narrative is in danger of becoming institutionalised within the FE psyche and it is for this reason that I make this plea to those responsible for the oversight of the FE system.

History proves that only communities that possess the shared resolve, compassion and unity to overcome such challenges, retain cohesion.

Whilst the stakes for me personally are low, for the sakes of learners, communities and the amazing people who work in this great sector of ours, I live in hope that FE can adopt a similar capacity.

Perhaps, we can take inspiration from 100 years ago: “We ceased fighting today and I have seen the last shot fired. A thing I never dreamt was possible in my wildest dreams. No more danger, no more wars and no more mud and misery.”

Always in hope,

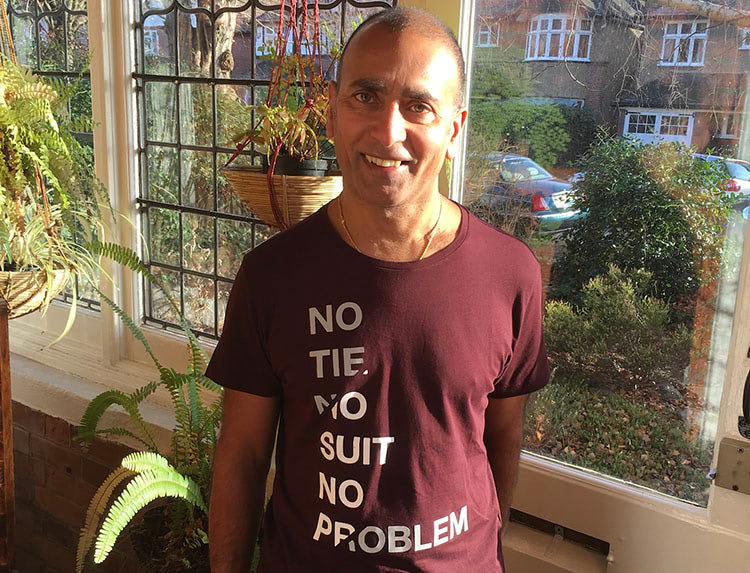

Amarjit Basi

Postnote to my letter:

At the time, I received over 100 responses, all from senior leaders active within the FE sector – many through their personal / non-professional contact sources, given the climate prevalent at that time. I didn’t receive a single reply from any of the institutions responsible for the oversight of FE.

Perhaps the timing, events and history were not right then. Things change….

All those holding publically accountable posts must surely recognise that the demand for racial justice now has a new and unstoppable urgency.

BFELG therefore formally calls for “an open, honest and solutions-focused dialogue” to address the systemic barriers that persist in addressing ‘Anti-racism’ in FE.

Responses