Closing the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers #FEsavedME

Today (25 Jul) the Education Policy Institute (EPI) publishes its Annual Report on the state of education in England – including the progress made in closing the gap in attainment between disadvantaged pupils and their peers.

The Education in England: Annual Report 2018 considers how the disadvantage gap has changed since 2011 and how it varies across the country. Colleges do a lot of work to help the disadvantaged.

In response to the new report, Catherine Sezen, Senior Policy Manager at the Association of Colleges, said:

“Unfortunately, a lack of funding has made running a college harder than ever, just at a time when colleges want to provide a full and rich curriculum and support for young people and adults. The balance between balancing the books and meeting students’ needs is not an easy one. “Colleges are inclusive and help people to make the most of their talents and ambitions and drive social mobility, especially for those who are from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“With additional funding, colleges could do much more. They are already doing so much to help businesses improve productivity and drive economic growth and they are rooted in and committed to their communities and drive tolerance and well-being. They are an essential part of England’s education system.”

Tackling the disadvantaged gap is a key priority for the Government. They have established the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) with a £137 million grant to identify the best methods of raising achievement in disadvantaged pupils.

DfE are also investing a further £72 million in 12 opportunity areas over three financial years to combat social mobility issues, prioritising resource and bringing local and national partners together. These 12 areas will also benefit from a share of £22 million through the Essential Life Skills programme to help young people in these areas develop life skills and employability.

Children and Families Minister Nadhim Zahawi said:

Closing the attainment gap to make sure every child fulfils their potential is a key priority for this Government. In fact, the gap has closed by 3.2% in the last year alone – one of the highest reductions we’ve seen since 2011.

To ensure this continues, we are targeting support at some of the poorest areas of the country through our £72m Opportunity Areas programme and our Social Mobility Action Plan is focusing £800 million of resources on helping disadvantaged children.

This builds on the 1.9 million more children now in good or outstanding schools than in 2010 – up from 66% of pupils in 2010 to 86% of pupils as of March 2018.

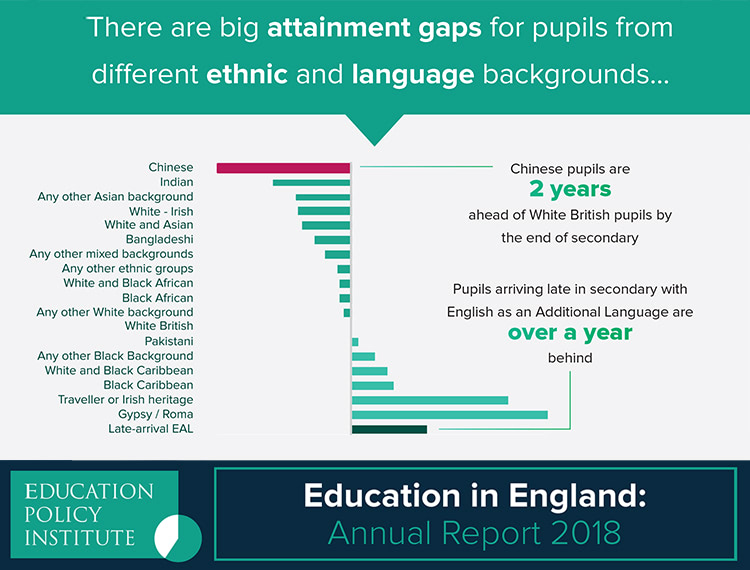

The report also looks at how pupils from different backgrounds perform, and, for the first time, looks at the post-16 routes taken by disadvantaged students and their peers. The underlying causes of educational disadvantage are also examined – with several policy recommendations proposed.

The research is based on the latest available data from the Department for Education, with ‘disadvantaged’ referring to those entitled to free school meals.

Key findings

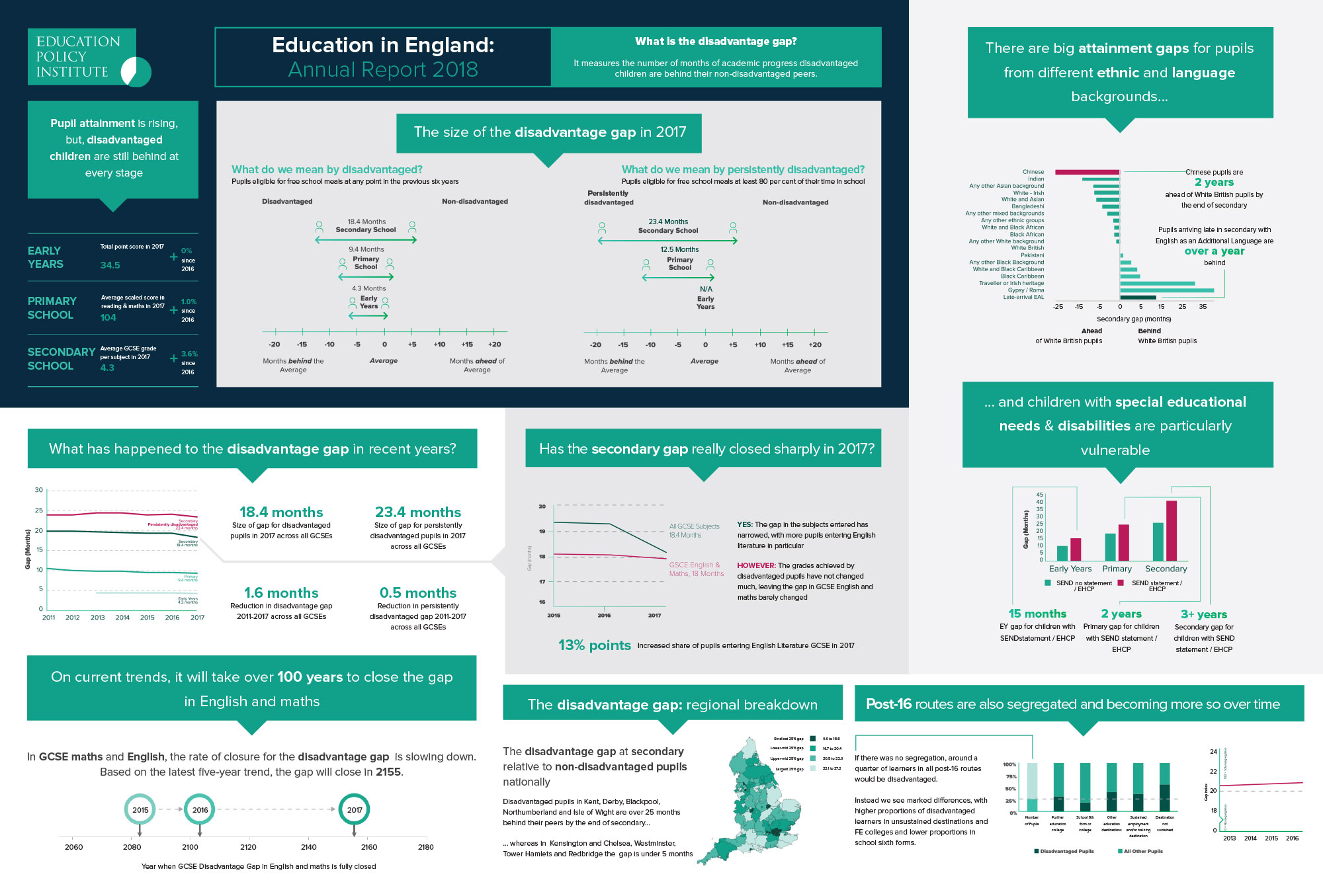

The disadvantage gap: overall trends

- Overall, there is little change in the gap in school attainment between disadvantaged pupils and their peers. In early years and primary phases, the gap is 4.3 and 9.4 months respectively.

- On the best measure of the disadvantaged gap at the end of secondary education (the English Language and Maths gap), there has been a significant slowdown in the rate of gap closure over the last few years – threatening the ambition of significantly greater social mobility.

- For the most persistently disadvantaged pupils, there has been no closure at all in the (English and Maths), disadvantaged gap since 2011.

- At secondary level, the disadvantage gap across all GCSE subjects closed faster than in previous years, standing at 18.4 months in 2017 (compared to 19.3 months in 2016).

- However the apparent narrowing of the disadvantage gap is caused largely by more disadvantaged pupils entering more ‘academic’ subjects – which have historically had smaller disadvantage gaps. This appears to be a result of recent government reforms – the English Baccalaureate and Progress 8 measures.

- Our research indicates that these accountability reforms are more likely to be the cause of a reduction in the size of the gap than improvements in pupil performance.

The disadvantage gap in English and maths

- Examining the gap in the compulsory GCSE subjects of English and maths gives us a more reliable assessment of the trend of the gap and a more robust basis for estimating how long it is likely to take to close. This is because English (language) and maths have been less affected by recent government reforms.

- In these subjects, we find that the rate at which the disadvantage gap is closing has slowed considerably: standing at 18.0 months in 2017, compared to 18.1 months in 2016.

- Strikingly, this also means that if current slow rates of progress in gap narrowing are maintained, the gap in English and maths would take well over 100 years to close – with similar outcomes between disadvantaged pupils and their more affluent peers not realised until the year 2155.

Regional trends

Levels of educational disadvantage have become firmly entrenched in some English regions:

- Disadvantaged pupils in several areas in the North East are behind their peers by as much as two years by the end of secondary. This includes Northumberland (26.1 months), Sunderland (23.6 months), Hartlepool (24.1 months), Redcar and Cleveland (23.4 months), and Kingston upon Hull (23.0 months).

- Poorer pupils also face a struggle in the East of England – in areas such as Norfolk (23.5 months), Lincolnshire (23.3 months) and Northamptonshire (22.1 months).

- Some areas however, have seen great success. Tower Hamlets, Islington and Hackney – areas with large proportions of persistently disadvantaged pupils – perform just as well as areas with very few of these pupils – such as Surrey and West Sussex.

Assessing which areas have progressed with tackling levels of disadvantage, and which have been ineffective since 2012, we also find:

- In parts of the South, such the Isle of Wight, Luton, Greenwich and Dorset, the gap has worsened since 2012 – as well as in parts of the Midlands, including Derby and Telford and Wrekin.

- However, some areas have been more effective in improving outcomes for the disadvantaged since 2012 – such as Slough, Wokingham, Barking and Dagenham and Southend-on-Sea, Rutland and Oldham.

The largest and smallest absolute gaps at secondary:

- The areas with the largest absolute disadvantage gaps are: Isle of Wight (27.2 months), Northumberland (26.1 months), Blackpool (25.8 months), Derby (25.5 months), Kent (25.4 months), Salford (24.7 months), Telford and Wrekin (24.6 months), Peterborough (24.2 months), Sheffield (24. 2 months) and Darlington (24.1 months).

- The areas with the smallest gaps are: Kensington and Chelsea (-2.5 months), Westminster (0.8 months), Tower Hamlets (3.8 months), Redbridge (4.5 months), Hackney(5.0 months), Newham (5.0 months), Hounslow (6.0 months), Southwark (6.0 months), Barnet (6.9 months) and Wandsworth (7.0 months).

The full set of regional and local findings can be accessed here.

Post-16 routes

- Comparing the routes of disadvantaged students and non-disadvantaged students after they finish their GCSEs, we find that post-16 education is becoming more segregated.

- A higher proportion of non-disadvantaged pupils are entering sixth forms, compared to disadvantaged pupils.

- In 2016, our Segregation Index stood at 21.2 per cent – meaning that 21.2 per cent of disadvantaged students would need to alter their post-16 routes in order to match those of non-disadvantaged students.

- Segregation levels have risen from 2013, when they stood at 20.6 in our Index.

Tackling disadvantage in education: policy recommendations

Despite successive governments promoting targeted intervention programmes, progress in closing the gap has slowed and the gap continues to widen as children progress through school. A strong evidence base, however, does exist for tackling educational inequality. Policy-makers should focus on the following interventions:

- Equalise access to high quality early years provision;

- Ensure a high quality and stable teaching workforce across the country, including in the most disadvantaged schools;

- Prioritise pupil well-being alongside academic attainment;

- Ensure early and sustained additional support for those who are behind with attainment;

- Provide access to a broad curriculum that includes out-of-classroom experiences;

- Promote a strategy of poverty alleviation – which forms the basis of a programme to improve the attainment of disadvantaged pupils, and

- Support maternal health and well-being throughout childhood.

A detailed review of the drivers behind the education disadvantage gap, published alongside this report, can be read here.

Full set of documents

Responses