Are GCSE, AS and A level exam grades “reliable to one grade either way” reliable enough?

School exam grades are important. They determine students’ destinies. But are grades as reliable as we might expect? Perhaps not: in 2020, Ofqual’s Chief Regulator admitted that grades “are reliable to one grade either way”. Is that reliable enough? Imagine this question were posed in a court of law…

Stage directions. The curtain opens to reveal a court room.

The prosecuting barrister is about to give her final speech in a (totally imaginary, of course!) case concerning the (true) (un)reliability of GCSE, AS and A level grades…

She rises; takes her spectacles in her right hand; turns. She carries no papers; needs no notes. She speaks from the heart.

‘Ladies and gentlemen of the jury. The central question it is your duty to answer today is whether or not the defendant has failed to deliver its statutory obligation – an obligation set out in Section 128 of the Apprenticeships, Skills, Children and Learning Act 2009, as amended by Section 22 of the Education Act 2011, “to secure that regulated qualifications give a reliable indication of knowledge, skills and understanding”.

‘In many trials, the evidence is piecemeal, perhaps circumstantial; a trace here, some DNA there; a GPS location of a mobile phone, an incriminating email. These proceedings, however, are unique as regards the clarity and provenance of the evidence. In this case, there is not just a smoking gun but a veritable smoking howitzer – the statement, made in evidence to the Education Select Committee at their hearing of September 2020, that exam grades “are reliable to one grade either way”.

‘“Reliable to one grade either way.”

‘What does that mean?

‘What it means is this. That an A-level certificate showing, say, Geography, Grade B, is in fact declaring that “The grade the candidate truly merits might be grade B. But it might be grade C. Or even grade A. No one knows.”

‘“Reliable to one grade either way.”

‘What use is that to the student denied the place-of-their-dreams for want of a single grade? Or to the student awarded grade 3, ‘fail’, in GCSE English, yet who truly merited grade 4, ‘pass’. But because the certificate shows only grade 3, that candidate loses a year of development, and is forced to re-sit. With who-knows-what implications on his, or her, mental health.

‘Unreliable grades do great damage. Why, then, doesn’t every certificate show, in BIG LETTERS, WARNING: THE GRADES ON THIS CERTIFICATE ARE RELIABLE ONLY TO ONE GRADE EITHER WAY? That, after all, is the truth. And declaring that truth would ensure that everyone taking a decision using grades is aware of just how unreliable GCSE, AS and A level grades really are, so that the damage that might otherwise be done is at least partly mitigated.

She pauses; sees the heads nodding in agreement; senses she has captured the jury’s attention.

‘As we saw yesterday, the admission that grades “are reliable to one grade either way” did not come out-of-the-blue, but is based on the defendant’s own research, as reported in the defendant’s document, Marking Consistency Metrics – an update, published on 27 November 2018.

‘Let me summarise the key points here.

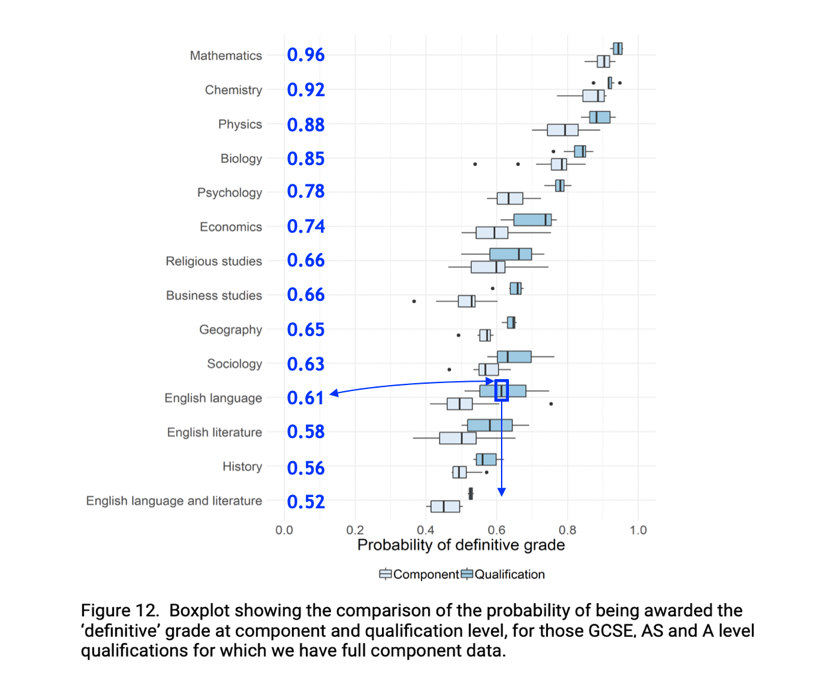

‘You will recall the evidence relating to Exhibit A, which shows the defendant’s measures of the average reliability of GCSE, AS and A level grades for each of 14 subjects, on a scale from 0.00 (grades totally unreliable) to 1.00 (grades totally reliable). As can be seen, grade reliability varies by subject, with Mathematics having a reliability of about 0.96; Biology, 0.85; English Language, 0.61; and Combined English Language and Literature, 0.52.

(Based on diagram on page 21 here)

‘Let me remind you what these numbers mean. As we all know, and as the defendant acknowledges, for exams based largely on essays, and which allow students freedom to express their thoughts in their own words, “it is possible for two examiners to give different but appropriate marks to the same answer”. An exam might therefore be given a total of 64 marks, or, perhaps, the “different”, but equally “appropriate”, total of 66. If grade B is all marks from 60 to 69 , then the candidate’s certificate shows grade B no matter who did the marking. But if the B/A grade boundary is 65/66, then the certificate will show either grade B or grade A depending on the lottery of who happened to mark the script.

‘Which of these two grades is right?

‘The defendant resolves this dilemma by designating the grade resulting from the mark of a senior examiner as “definitive” or “true”. Which takes us to Exhibit A. As we examined in detail yesterday, this shows the results of the defendant’s extensive research in which entire cohorts of exam scripts were each marked by suitably qualified ‘ordinary’ examiners, and also, independently, by subject senior examiners.

‘Every script therefore had two marks, from ‘ordinary’ and senior examiners respectively; two marks that might be the same, but also two marks that might be “different but appropriate”. Each of these two marks has a corresponding grade, which, once again, might be the same. But if those “different but appropriate” marks straddle a grade boundary, the resulting two grades will be different. Yet only one, that attributable to the senior examiner, is “definitive”, the benchmark of ‘right’.

Since the bulk of exam marking is done ‘ordinary’ examiners, the grades shown on candidates’ certificates are very largely those attributable to ‘ordinary’ examiners, not senior ones. So it’s really important that there is a very high likelihood that the grades on a certificate are “definitive”, even when the marking is done by ‘ordinary’ examiners.

‘Exhibit A shows what that likelihood is, for each of the 14 subjects studied. Taking English Language as an example, the defendant’s reliability measure of 0.61 tells us that for any exam in that subject, about 61 out of every 100 candidates receive a certificate on which the grade is the same as the senior examiner’s “definitive” or “true” grade, and therefore right. But for about 39 candidates in every 100, the grade on the certificate is different from that awarded by a senior examiner, and so that grade cannot be “definitive”, nor can it be “true”.

‘How might you describe such a grade? Non-definitive? Untrue? False?

‘I prefer the plain word ‘wrong’.

‘Let me make all that real.

‘According to official statistics, in the summer of 2022, 697,827 candidates in England sat GCSE English.

‘And according to Exhibit A, the likelihood of being awarded the right grade is 0.61.

‘The number of candidates awarded the “definitive” grade for 2022 GCSE English can therefore be calculated as 0.61 x 697,827 = 425,674.

‘Which tells us that 697,827 – 425,674 = 272,153 candidates received certificates showing a “non-definitive” grade.

‘That’s over a quarter of a million young people in England awarded the wrong grade in GCSE English just last year alone. Is that evidence of success in “securing that regulated qualifications give a reliable indication of knowledge, skills and understanding”? Or is it undeniable proof of failure?’

Another pause, as she holds the eyes of every member of the jury.

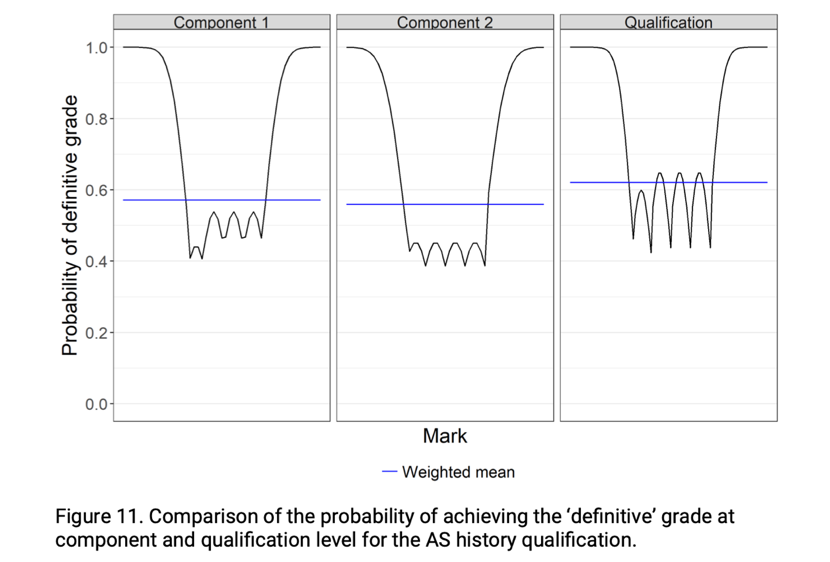

‘As I explained earlier, the reliability measures shown in Exhibit A are whole-cohort averages across the entire mark range. From an individual candidate’s point-of-view, a more important question is “what is the reliability of the grade associated with a script given a specific mark?”. The answer to that question is also provided by the defendant’s own documents – so, for example, Exhibit B reproduces another chart from the defendant’s 2018 report showing the mark-by-mark reliability of AS history grades.

(Diagram on page 20 here)

‘The most startling feature of Exhibit B is that the reliability of any script marked at, or close to, any grade boundary is less than 50%. Yes, less than 50%. More scripts are awarded a non-“definitive”, “untrue” grade than the “definitive”, “true” one! Tossing a coin would be more fair. Is that evidence of success in “securing that regulated qualifications give a reliable indication of knowledge, skills and understanding”? Or is it undeniable proof of failure?

‘You might think that the appeals process will right these wrongs.

‘Not so. For the three reasons I presented in detail yesterday. To summarise…

‘Firstly, many candidates do not appeal because they have no basis on which to judge whether the grade they are awarded is right or wrong. They accept the result they are given; they trust ‘the system’.

‘Secondly, many candidates, especially those in state-funded schools, do not appeal because the fee is a disincentive.

‘But it is the third reason that is the biggest barrier to justice – a reason attributable to the current rules for appeals, as best explained by example.

‘Suppose an exam has the B/A grade boundary set at 65/66. If a student achieves 64 marks, the student’s certificate will therefore show grade B. Suppose further that an equally valid mark – a mark that is “different but appropriate” – is 66, grade A. If that higher mark, 66, is that of a senior examiner, the “definitive” or “true” grade is A, and the B on the certificate is “non-definitive”, “false” or just plain wrong. But under the current rules for appeals, a re-mark by a senior examiner is not allowed, for, to quote the defendant once more, “It is not fair to allow some students to have a second bite of the cherry by giving them a higher mark on review, when the first mark was perfectly appropriate”.

‘Yes, the original, lower, ‘ordinary’ examiner’s mark, 64, grade B, is indeed “perfectly appropriate”. But so is the higher, senior examiner’s mark, 66, corresponding to the “definitive” grade A. Yet to discover this “definitive” grade is dismissed as being an “unfair second bite of the cherry”.

‘The first bite of that cherry, however, was poisoned. And the defendant’s own rules deny access to the antidote. The result? The candidate’s certificate will continue to show the wrong grade. For ever.

‘Is this “securing that regulated qualifications give a reliable indication of knowledge, skills and understanding”? I think not.

‘But, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, it is not my opinion that counts. It is your wise judgement. Only you can decide whether or not the defendant has failed in its statutory duty.’

She turns to the public gallery.

‘And it is for you, the public, to determine whether or not it matters.’

Yes, this ‘trial’ is imaginary. But the facts referred to are true, as you can verify from the links. And something rather similar nearly happened in August 2020, albeit in a rather different context, the aftermath of the algorithm fiasco.

By Dennis Sherwood, campaigner for the delivery of reliable and trustworthy school exam grades

#exams #grades #GCSE #AS #Alevel @FENews @Canburypress @noookophile

Biographical note

Dennis Sherwood is a campaigner for the delivery of reliable and trustworthy school exam grades, and the author of Missing the Mark – Why so many school exam grades are wrong, and how to get results we can trust, published by Canbury Press.

Responses