The Optimal Approach to Project Management in HE & FE: Traverse the Brook with Bravery

Educational establishments can be notoriously tricky beasts to tame.

At their worst they are illogically structured, allowing for disparate groups of staff to work in silos without contributing to a wider strategy; working within outdated and unproductive processes and regulations, which can be entirely counterproductive to student outcomes. At their best, however, they awaken and utilise the intellect within staff and stakeholders; enabling academics, administrators, support services and students to collaborate rigorously and innovatively. This, I believe, is the sweet spot for universities and colleges to work within – understanding and respecting the traditions and status quo, yet being brave enough to move things forward in order to contemporize.

The structures and regulations that exist today were innovations of the past.

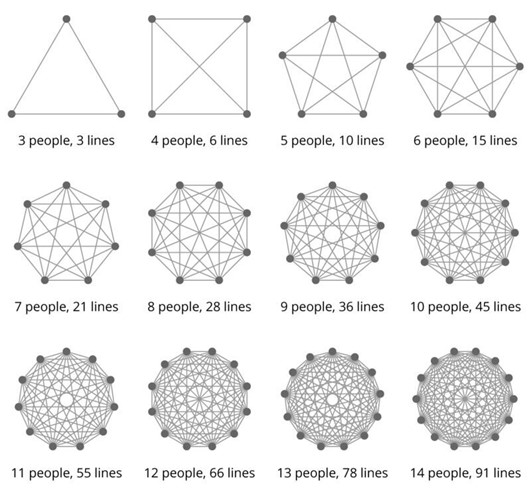

It’s vital to accept them and understand them before considering how we can innovate – but innovate we must. Without structure we cannot have innovative rebellion. Universities must therefore not be frightened to drive forward new ways of working. The diagram below, based on Brooks’ Law, has prompted some heated discussions with peers recently, and it highlights some of the potential problems faced by academic institutions within the projects they initiate.

Brooks’ Law – rules on project management

Brooks’ Law observes that adding manpower to projects which are already working to a tight deadline can cause delays and put constraints upon team members who are working within the project. The Law also captures some other observations, stated below, which it considers as rules within project management.

Firstly, the fact it takes time for new members of the project to ‘get up to speed’, as they become educated about the work which has preceded them. This, in turn, temporarily diminishes productivity.

Secondly, communication overheads increase with each additional member that is added to the project team. The diagram indicates this succinctly and, if we presume that team members should all communicate with each other, it is inevitable that more time will be needed. This ‘loss of time’ can be negated by more hierarchical structures, of course, but isn’t that precisely what an organisation ought to be attempting to remove in order to achieve a truly collaborative output?

Thirdly, we must question whether adding more people to a project will expedite it. Some tasks are easily divisible and do not always rely on differing levels of expertise, but we are beyond the industrial revolution now and productivity and output is often more nuanced. Simply adding more people may not move a project closer to successful completion.

The exceptions to Brooks’ Law: it’s about the people, not the numbers

There are, however, exceptions to Brooks’ Law. For instance, it may sometimes be necessary to engage a wider number of team members within a project, and that approach is perfectly valid – providing careful foresight and planning of the number of people involved takes place before the project gets underway. Mistakes made in planning and scheduling are the major cause of projects being delivered late, or over budget.

Secondly, the type of people involved in the project are clearly key to its success. Ensuring all responsibilities are accounted for, with people who have the requisite expertise, attributes and motivations to successfully deliver them is key. Good segmentation of workloads, with appropriate communication of that, deadlines, and reporting mechanisms, will ensure project team members are kept on track to deliver.

Furthermore, it should be noted that new members of a team will inevitably affect the existing culture of the existing team. This effect can be positive or negative, but your project will be entering the realms of the unknown once you introduce new members midway through, and amended teams will likely need to go through the forming, norming and storming phases before they are able to perform to capacity.

Situational leadership is vital within education

A sceptic might view Brooks’ Law as a means of simply cutting costs and quickening processes; one which is favoured ahead of appreciating diversity and allowing space for considered thought. But, running a project, team or organisation is, as we know, not as simple as that. The choice is not binary, and it is rarely possible to simplify things to the extent that one approach will always be the correct one.

My leadership and management experience begun nigh on two decades ago and what I’ve learnt in that time – across several industries – is that situational leadership is vital. In the education sector; particularly HE and FE; the way projects are designed, run and managed is often key to an organisation’s success. Therefore, time spent in planning those projects and the type and number of people within project teams is vital.

So, in conclusion – and with Brooks’ Law in mind – I present my own personal thoughts on successful project management within transformative educational settings, below.

Top tips for educational project management

- Find the sweet spot in terms of the volume of team members. This is totally dependent on the project itself, but it pays to give consideration to Brooks’ Law in the planning phase.

- Blend your team to ensure representation; of stakeholders, of expertise, and of departments – but don’t expect to keep everybody happy. Negotiating what works, and what the project and team members need is a key – and continual – element of project management. It goes without saying that you should prioritise the macro, not the micro, both in planning and in execution.

- Bring down the ivory towers. Teams are always in it together. Get together, whether virtually or in person.

- Leadership isn’t about having the power to override. It’s about enabling, empowering and recognising talent, expertise and motivations. We all know that if you recruit good people then they can be trusted to get the job done, so trust them.

- Focus on what is needed now. The world is full of unknowns. Trying to second guess every possible future scenario will take you further away from a great solution today. Innovation never stops – we’re just a part of the process.

- Get cracking! Doing something, quickly, is the best way to move your organisation forward. Running a pilot is a great way to get some initial data through a no-risk, small input approach. Start now! However…

- Value outcome over output – a successful project isn’t merely one which focuses on hitting deadlines. It’s important to deliver on strategic aims and objectives, because the I in KPI in an indicator. It’s useful, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. Find the current narrative and, if necessary, re-write it to deliver a happy ending.

- Keep people in sync with each other. Keep the reporting mechanisms simple, brief, and with human interaction if possible. Ditch the long reports, spreadsheets and emails – one-page update briefs are far more palatable. Also, consider whether everyone within a team needs to know what each other is doing, or whether a suitable delineation between roles and responsibilities will be enough to prevent that.

- Be patient. Remember the Mike Tyson quote ‘Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face’. Things will inevitably go wrong at some point. Accept that. The world will keep turning. Each small failure is getting you closer to success.

- Find a way to deliver the right solution. Don’t just make improvements through minor optimisations; be brave, innovate, do things differently, find a way.

Dr Rod Brazier

Principal

London College of Contemporary Arts

Responses