People want to see free speech thrive at universities … just not for racists, Holocaust deniers or advocates of religious violence

As part of forthcoming work in partnership with the Higher Education Policy Institute (@HEPI_news), the @UPP_Foundation commissioned detailed polling from @PublicFirst_PF on public attitudes towards various elements of higher education.

Given the current interest in free speech issues, we are releasing an excerpt of this polling ahead of the full results being published in a few weeks’ time.

Richard Brabner, the Director of the UPP Foundation, said:

‘These results show there are lessons for all sides in this debate. Free speech is popular. On a range of different contentious issues, the public – including 18-24 year olds and across political boundaries – support allowing controversial speakers on campus, even if they don’t agree with their views.

‘But equally, those pushing for a blanket protection for free speech should be under no illusion. The public does not approve of a libertarian free for all. When it comes to racist speakers and Holocaust deniers the public do not want them anywhere near our universities.’

In media discussions over the past week around the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill, the Government have found themselves in some difficulty when faced with hypothetical situations and, specifically, on the right of Holocaust deniers to speak on campus.

Matt Western MP, Labour’s Shadow Universities Minister, said:

“The Conservatives are out of step with public opinion.

“Ministers have created a row over freedom of speech which panders to those whose sole aim is to hurt and offend.

“The Government must explain why they are determined to press ahead with such unpopular and damaging plans.”

Interviewed on BBC Radio 4’s PM programme on Wednesday, Universities Minister Michelle Donelan MP was asked directly if it meant a Holocaust denier would be protected under these plans because it is not illegal in the UK.

Interviewed on BBC Radio 4’s PM programme on Wednesday, Universities Minister Michelle Donelan MP was asked directly if it meant a Holocaust denier would be protected under these plans because it is not illegal in the UK.

Michelle said: “A lot of these things that we would be standing up for would be hugely offensive, would be hugely hurtful.”

This example illustrates some of the concerns which many in the higher education sector have about the forthcoming legislation. The Government has made no secret of its desire to campaign on issues of free speech and against ‘cancel culture’ broadly, including in higher education – and it is reasonable to believe they think this approach chimes with the public and particularly with Conservative voters.

The polling of over 2,000 adults shows that, in principle, the public is in favour of free speech. When asked, a majority of people say that people should be allowed to speak to students at university so long as their views are not illegal (55%). A more libertarian perspective, where nobody is prevented from speaking to students because of their opinions is less popular, with only around a quarter (24%) of the public supportive of this position.

People’s views change dramatically when faced with different scenarios of controversial speakers. Our polling offered ten plausible scenarios of speakers (many – if not all – of which would be widely considered to be controversial).

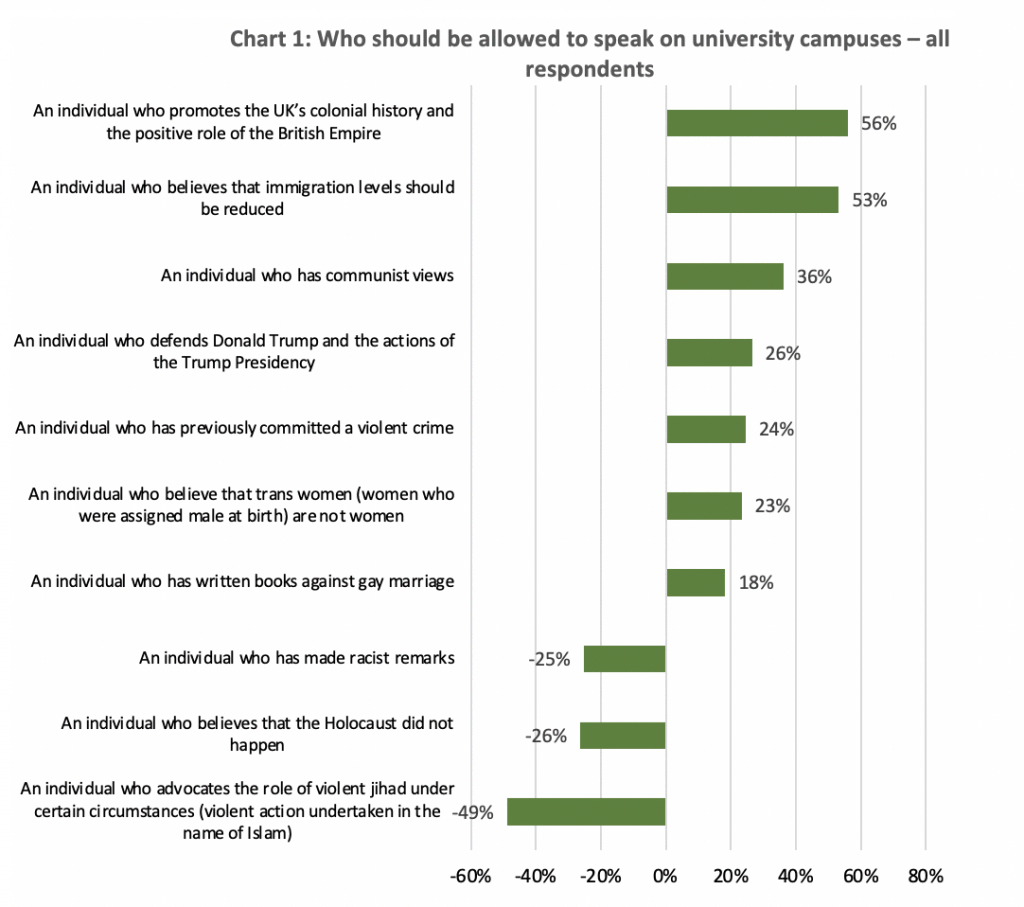

When asked, based purely on that one piece of information whether in principle such a person ‘should be allowed to speak at a university’, ‘should not’, or ‘don’t know’, people’s opinions range from a net 56% in favour through to a net -49%. It is worth emphasising that between 13% and 22% of respondents answered ‘don’t know’ to the scenarios, showing either the complexity of the issue or an unwillingness to give an opinion.

From the scenarios in our polling, the principle of allowing a Holocaust denier the right to speak at a university is one of the least supported, with a net percentage of -26% thinking they should be allowed to speak (29% ‘should’, 55% ‘should not’, 16% ‘don’t know’). So the Government’s clarifications at the end of the week that Holocaust deniers will ‘never, never, never’ be protected by the new legislation will be welcome news to much of the public.

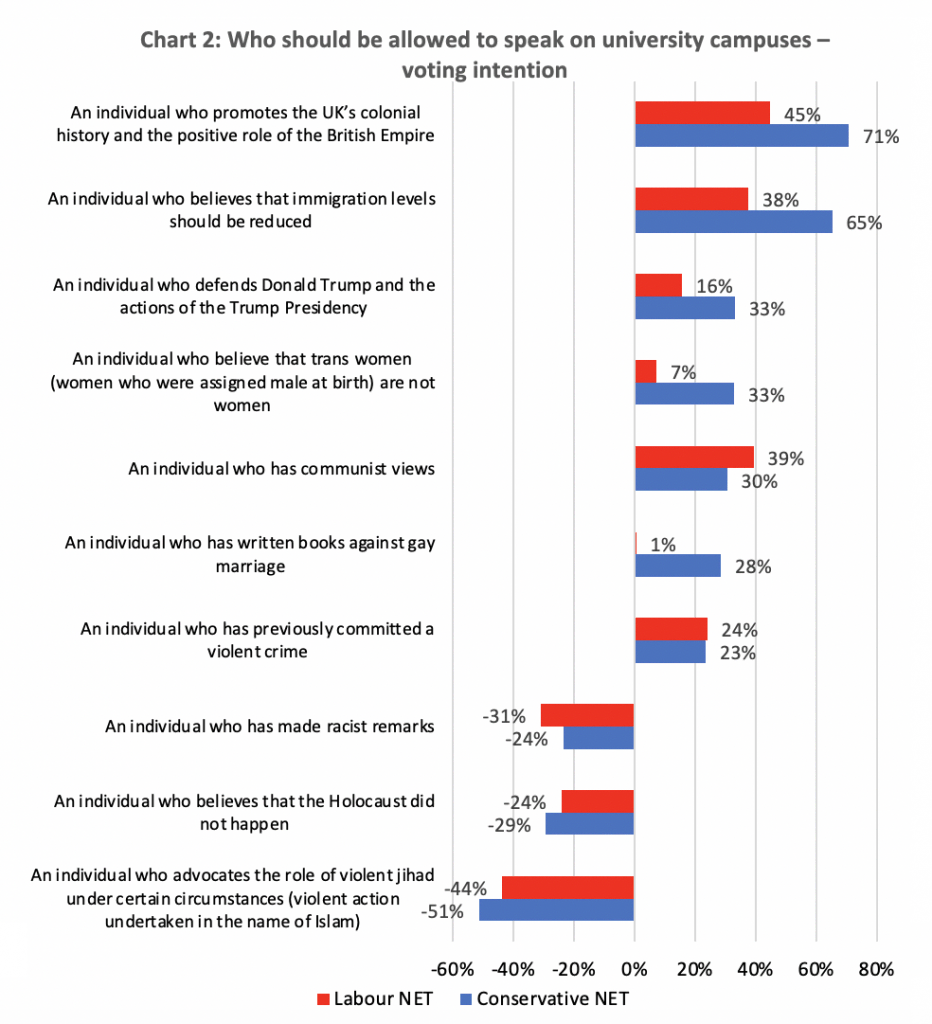

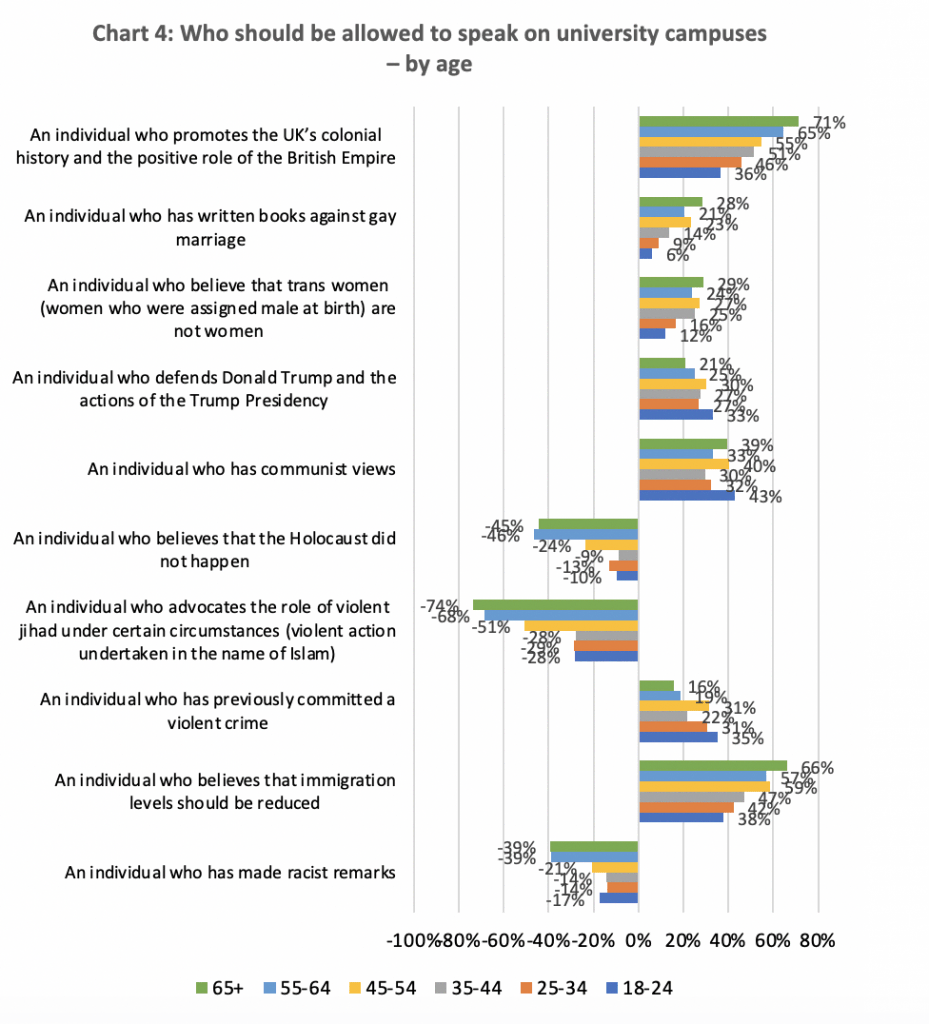

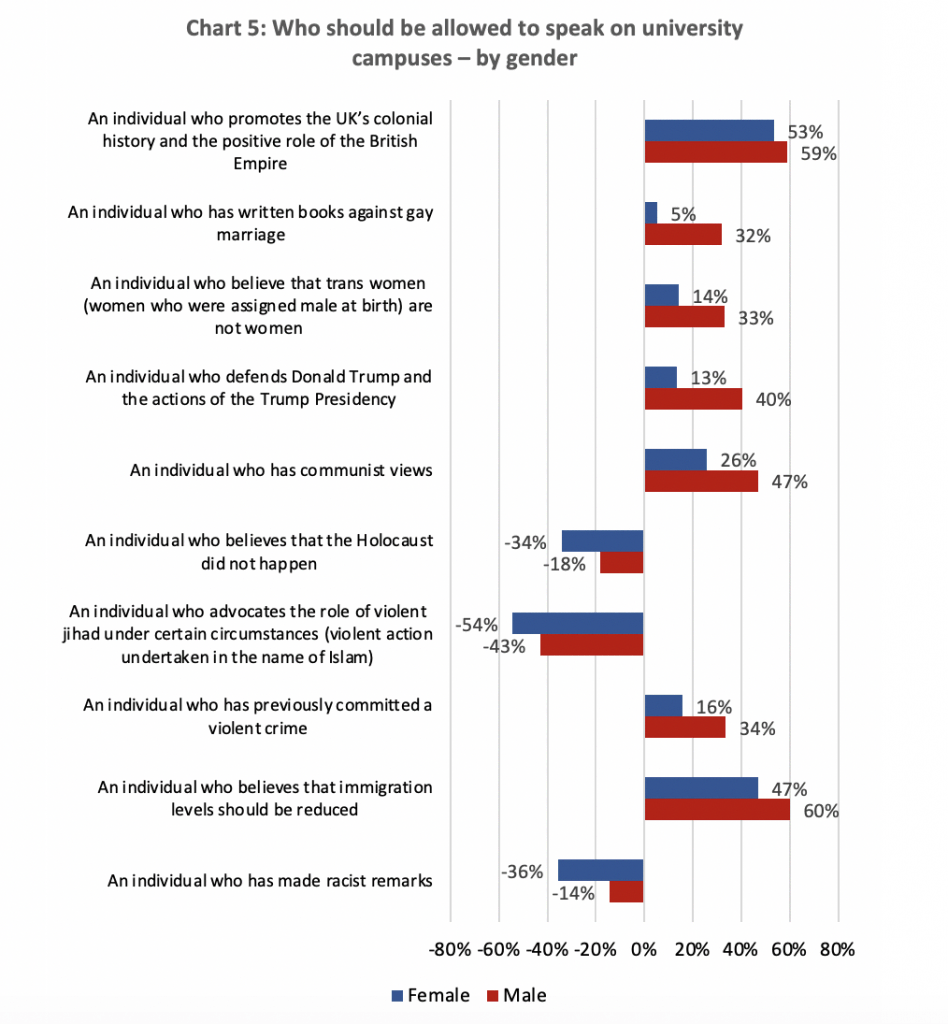

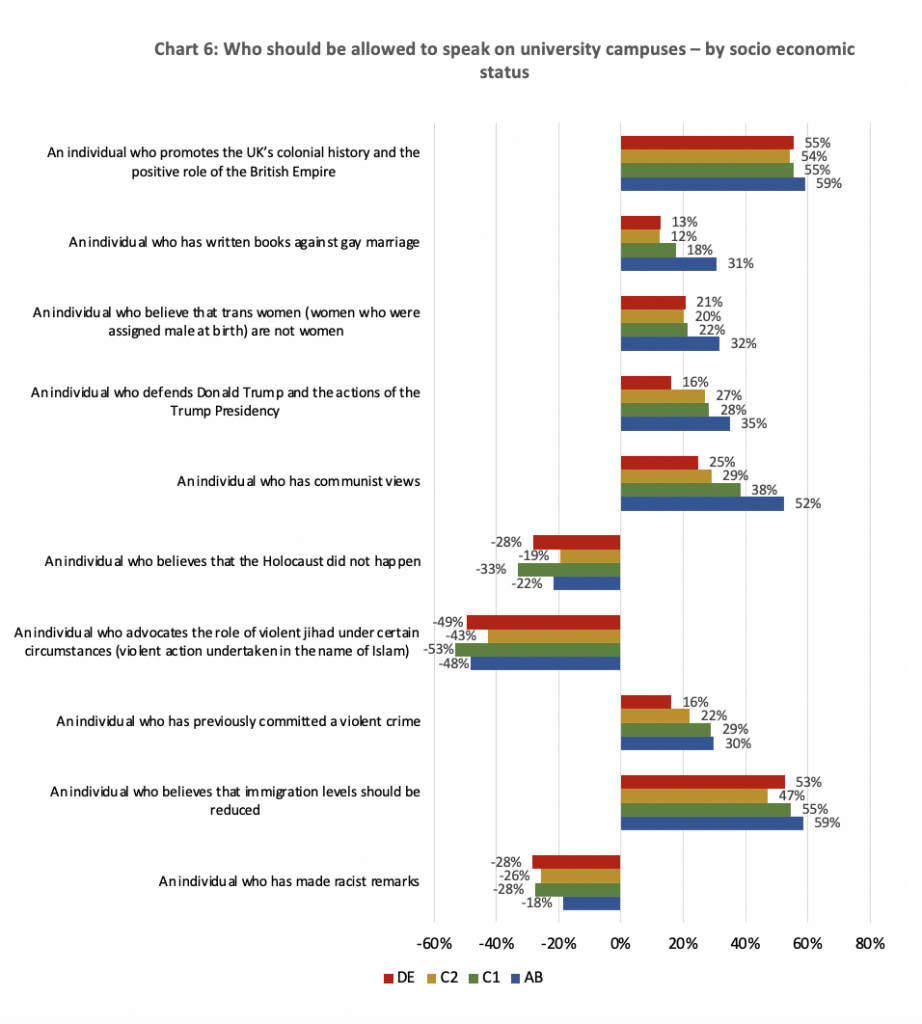

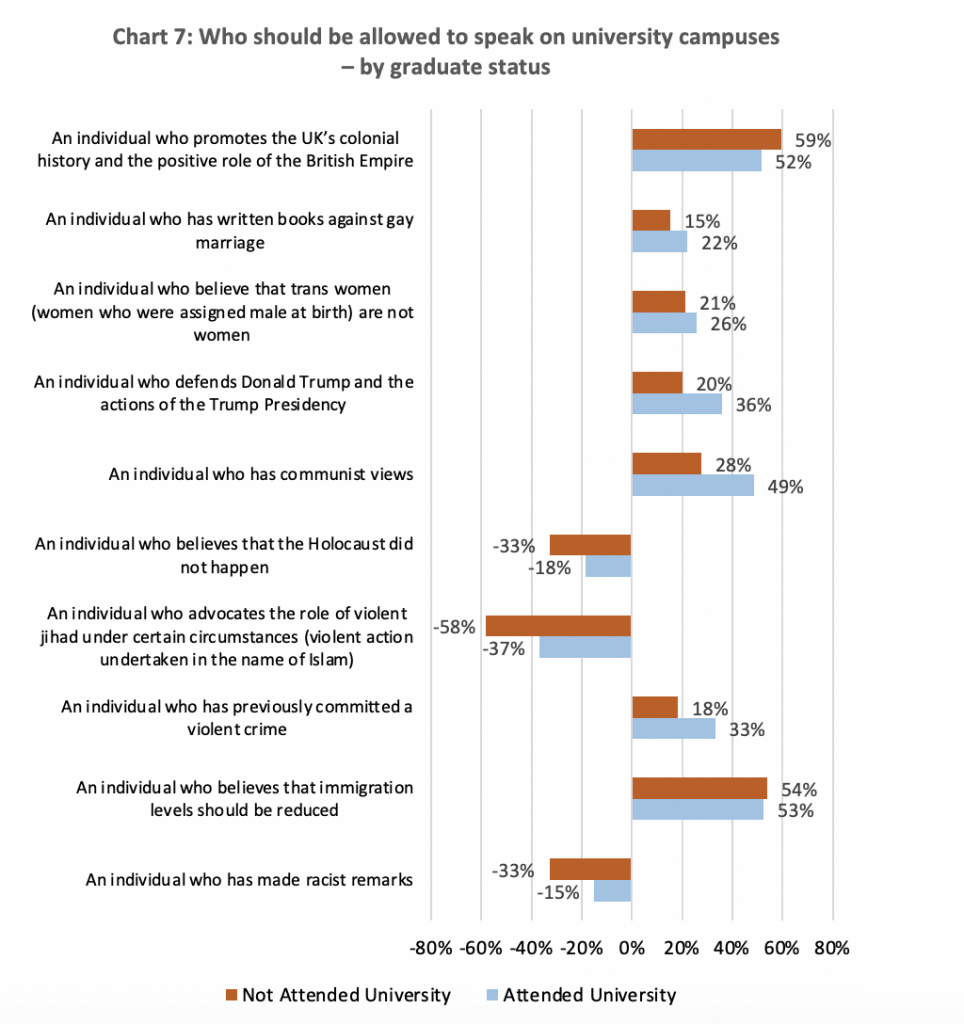

The following charts look at people’s responses by different cross breaks. For each one, we’ve presented a net score – that is, those who said such a person should speak, less those who said a person should not speak. We have excluded ‘Don’t Knows’ from the charts for ease of visibility – but again, it is worth noting that on these, around 10% to 25% of people say don’t know.

There are some differences by (self-identified) political opinion. Conservative voters are more likely to be supportive of free speech for six of the issues, with Labour voters being more supportive of four of them. There are large differences between major party voters on the questions of promoting the Empire, campaigning for reduced immigration levels (although both of these record substantial positive NET scores from Labour and Conservative voters), trans issues and gay marriage.

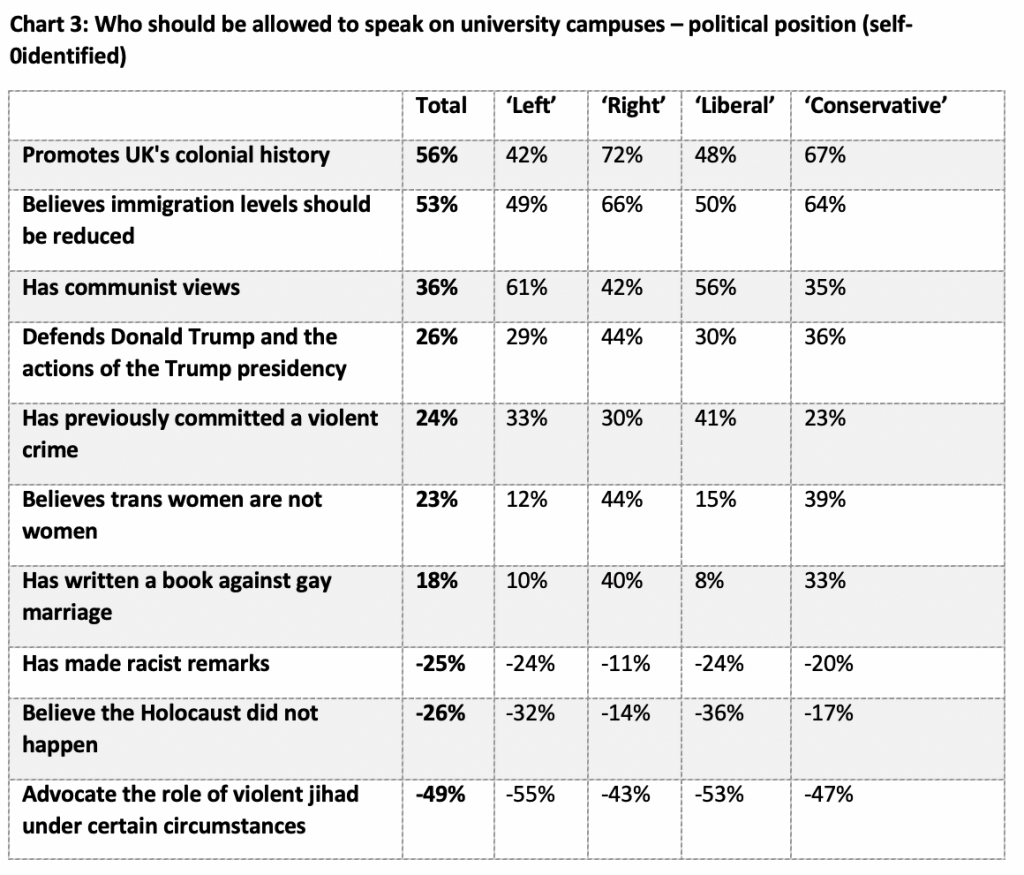

We can explore this further using self-defined political positions without reference to party labels. Naturally, people’s self-identification on these scales will only be so accurate, however the results indicate that people’s perceptions of who should be able to speak are linked with the content of what the individual believes rather than simply a general commitment to ‘freedom of speech’.

Younger people are more in favour of letting some people speak than older ones (particularly around crime, and communism and Trump supporters). But they are less supportive than older people of someone’s right to speak if they promote a positive role of the empire, are against gay marriage or don’t believe trans women are women (although in each of those cases, there are net positives within all age groups).

When split by gender, we can see that men are consistently more pro free speech than women. Across all ten of the examples, men are more likely to want the speaker to speak (though, net, they are also against allowing Holocaust deniers, jihadi advocates and racists to speak).

There are limited patterns by socio economic status. AB voters tend to be more pro free speech than DE voters, but on every issue apart from communism, the differences are moderate.

When looking at the responses of graduates versus non-graduates, we find that graduates are more pro free speech than non-graduates on 8 of our 10 examples – with non-graduates being more supportive of speakers defending the Empire and (more narrowly) calling for restrictions on immigration.

Finally, returning to the issue that caused so much discussion last week, of Holocaust denial, we can see by bringing all crossbreaks together that it is one of a small number of examples where every group and subgroup has more support for banning such speakers than for letting them speak.

Overall, there are major lessons for both sides of the debate. It is clear that a blanket call in favour of free speech is likely to find popular support. But the real finding is that people will respond very differently depending on the circumstances of the speaker in question.

For those who may think any controversial issue is problematic and that discussion should be constrained, it is worth noting that self-identified Labour voters and liberals are net in favour of seven out of these 10 speakers giving remarks on campuses – including those that promote the Empire and those who oppose trans rights. Similarly, young voters (aged 18 to 24) are net in favour of seven scenarios (with Holocaust denial being one of three in which they – as with every other age cohort – express net support for a ban).

The risk for the Government and those pushing for further free speech protections is that – as has happened this week – specific examples can quickly find their coalition of supporters falling apart, with Conservative voters in 2019, those on the Right, and older people, all liable to be less supportive of someone’s right to speak at university depending on the nature of their views expressed.

Methodology: On behalf of the UPP Foundation and HEPI, Public First ran a poll of 2,011 adults in England between 4 and 7 February 2021. These results are part of a broader survey on public attitudes towards higher education. The UPP Foundation and HEPI plan on publishing a joint report analysing the full results of the polling in coming weeks but, given the announcement in the Queen’s Speech, the UPP Foundation and HEPI have published the results pertaining to free speech to help inform the current debate. All results, especially those showing sub-groups of respondents will be subject to a margin of error.

Universities to comply with free speech duties or face sanctions

12th May 2021: Landmark Bill will require universities to promote freedom of speech on campus and legal duties will also be extended to students’ unions

A historic bill introduced in Parliament (12 May) will strengthen the legal duties on higher education providers in England to protect freedom of speech on campuses up and down the country, for students, academics and visiting speakers.

The Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill will bring in new measures that will require universities and colleges registered with the Office for Students to defend free speech and help stamp out unlawful ‘silencing’.

For the first time, these legal duties will also be extended to students’ unions, which, under the measures in the Bill, will have to take reasonably practicable steps to ensure lawful freedom of speech.

This delivers on a manifesto commitment to strengthen academic freedom and free speech in higher education and will help protect the reputation of our universities as centres of academic freedom. Universities, colleges and students’ unions that breach these duties may face sanctions, including fines.

Education Secretary Gavin Williamson said:

Education Secretary Gavin Williamson said:

It is a basic human right to be able to express ourselves freely and take part in rigorous debate. Our legal system allows us to articulate views which others may disagree with as long as they don’t meet the threshold of hate speech or inciting violence. This must be defended, nowhere more so than within our world-renowned universities.

Holding universities to account on the importance of freedom of speech in higher education is a milestone moment in fulfilling our manifesto commitment, protecting the rights of students and academics, and countering the chilling effect of censorship on campus once and for all.

A new Director for Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom will sit on the board of the Office for Students, with responsibility for investigations of breaches of the new freedom of speech duties, including a new complaints scheme for students, staff and visiting speakers who have suffered loss due to a breach.

The Bill comes in light of examples of a ‘chilling effect’ on students, staff and invited speakers feeling unable to speak out. In one incident, Bristol Middle East Forum was charged almost £500 in security costs to invite the Israeli Ambassador to speak at an event.

In another example, over one hundred academics signed a letter expressing public opposition to Professor Nigel Biggar’s research project ‘Ethics and Empire’, because he had said that British people should have ‘pride as well as shame’ in the Empire.

Registered higher education providers in England will have extended legal duties not only to take steps to secure freedom of speech and academic freedom, but also to promote these important values.

Universities Minister Michelle Donelan said:

Universities Minister Michelle Donelan said:

The values of freedom of speech and academic freedom are a huge part of what makes our higher education system so well respected around the world.

Which is why this government will tackle head on the growing chilling effect on our campuses which is silencing and censoring students, academics and visiting speakers.

This Bill will ensure universities not only protect free speech but promote it too. After all how can we expect society to progress or for opinions to modernise unless we can challenge the status quo?

The government has been clear throughout that it is important to distinguish between lawful, if offensive, views on one hand and unacceptable acts of abuse, intimidation, and violence on the other.

Higher education providers and students’ unions must ensure that they comply with their legal duties on discrimination and harassment as well as their legal duties to protect freedom of speech.

Responses