The Advanced British Standard – A huge missed opportunity

On 30 August FE News reported on a survey, carried out in the US by Business Name Generator, the key finding of which was that “84% of employees and managers believe new employees must possess soft skills and demonstrate this in the hiring process” – soft skills such as communication, problem-solving, critical thinking, self-motivation, flexibility, creativity and leadership.

Alas, it appears that this survey – and the many other reports published over the last few years stressing the importance of soft skills – have not been noticed by the government.

As we all know, at the Tory Party Conference in Manchester on 4 October, Prime Minister Sunak announced a flagship reform programme for education, with the speech’s soundbites supported by a 39-page report entitled “A world-class education system – The Advanced British Standard”.

To quote the report:

“This is a long term reform: it will take a decade to deliver in full”.

A decade.

Well, it’s not every day that the government announces a “long term reform” of education, and since even the government’s estimate is that the reform will take a decade to implement (mmm… government estimate…), the reform must be profound indeed.

What does the reform look like? What are the intended outcomes?

Page 36 of the government’s report provides the answers:

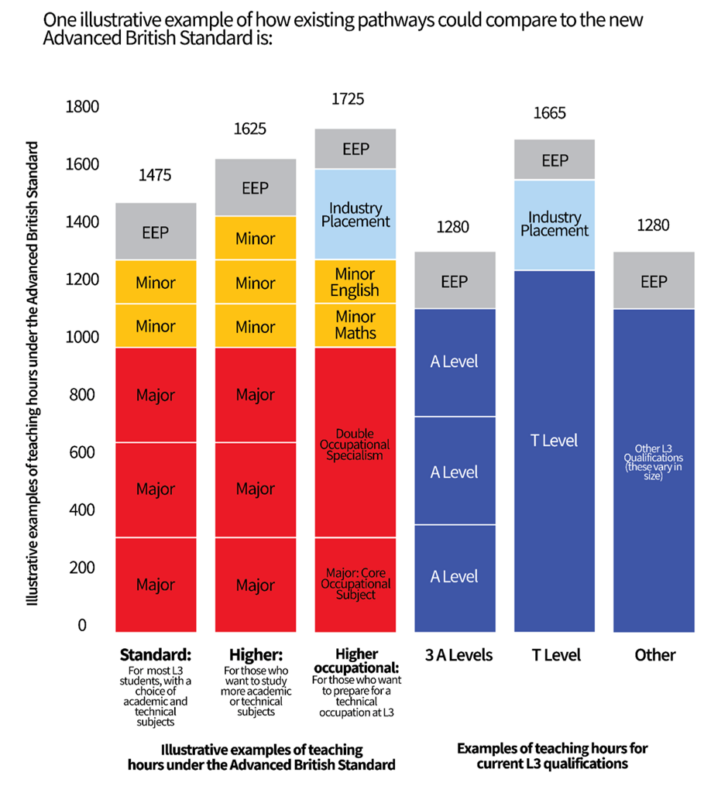

The outcome is that 16-18 year-olds will no longer study typically three A Levels or one T Level, but three “majors” and either two or three “minors”, with a condition that English and Maths must be included in the mix.

You might expect that the 39-page report would contain much more detail than the Prime Minister’s announcement. So prepare for a disappointment. One page is the contents, three are Gillian Keegan’s foreword, and a further five, the executive summary. That takes us to page 10, the first of a further 9 pages that celebrate the Tory government’s educational achievements since Michael Gove took over as Secretary of State in 2010.

So it’s not until page 20 that we learn about the reforms themselves, and although the remaining 19 pages are about the proposals, there is much repetition and very little detail beyond the key headlines (page 21):

- “We will deliver genuine parity of esteem between technical and academic routes”, as achieved by the replacement of the two qualification streams, A Levels and T Levels, by the single Advanced British Standard.

- “We will increase in quality teaching time”, explained as “We need to do more to increase students’ access to and time with high-quality teachers” – which is, I’m sure, a ‘good thing’ to do, but is phrased as if it were somehow the fault of the students, who, by inference, need to be encouraged and cajoled to attend classes. We have to wait until page 32 to read “This will be achieved by more funded teaching hours”. Ah. So the issue is nothing to do with students. It’s about the failure of the government to have provided sufficient funds in the past.

- “We will embed a core of essential knowledge”, this being code for “all 16-18 students must do Maths and English”.

- “We will ensure everyone studies a greater breadth of subjects”, as depicted in the diagram.

In addition, there are commitments to:

- “invest in teacher recruitment and retention by giving those who teach key shortage subjects a payment of up to £6,000, tax-free per year, if they are in the first five years of their career”

- “invest an additional c.£150 million each year to support those who do not pass maths and English GCSE at 16 to gain these qualifications”

- “invest an additional £40 million in the Education Endowment Foundation”

- “turbo-charge the best, evidence-based techniques for maths teaching [by investing] £60 million of additional funding for maths education over the next two years”.

That’s my summary of what’s in the report.

What about the curriculum?

But to me, much more important is what’s not in the report.

Take, for example, the word ‘curriculum’.

My word search identified 12 matches. Two of these refer to the current curriculum in England, and one to curricula elsewhere. The other nine are associated with the proposed curriculum-of-the-future, all associated with the adjectives “broad” or “balanced”, and, most frequently, “knowledge rich”, a term described in detail in a full page explanation written by Nick Gibb.

That page (15) is well-worth reading, for it sets the tone of the entire reform programme, most vividly in the first paragraph:

- It is very difficult to teach generic, transferrable skills, and most are based on key knowledge. For example, it is possible to learn scientific methods in the abstract, but a successful scientist has to know what an ‘anomalous’ result in their field looks like, which relies on deep knowledge.

My understanding of those words is that “generic, transferrable skills” are exactly those soft skills most valued by employers.

Yes, some of them are knowledge-based – you can’t solve the problem of how much carpet to buy if you don’t know how to measure the area of the floor.

But that first statement, that “it is very difficult to teach…”, makes me see red, for not only is this the excuse for ignoring those oh-so-important soft skills completely in the proposed reforms, but it is also, I believe, profoundly untrue. The soft skill of communication – or, to my mind, oracy – is the most natural skill to nurture, for every human being is endowed with the twin capabilities of thought and speech; the soft skill of creativity is very easy to teach if done in a thoughtful way; the soft skills of flexibility and leadership emerge as individuals gain experience of working in teams and learn the value of responding to other people in a positive and constructive way.

So, having dismissed “generic, transferrable skills” as unteachable, the role of the school is to foster “deep knowledge”.

What a missed opportunity.

Rather than proposing a reform of the curriculum, which would have real and lasting positive impact, the government’s BIG ANNOUNCEMENT proposes what is in essence merely a change in the structure of the time-table, along with some much-needed enhancements to funding.

Not only have the government not noticed the soft skills survey, they have ignored the key findings of The Times Education Commission, Rethinking Assessment, New Era Assessment and the many other studies stressing the importance of fundamental reform to what students are taught, and how they are assessed. Most importantly, there is no reference to the Scottish Government’s document In Our Future, published in June 2023, and to my mind a far more powerful proposition.

Oh dear.

And there’s much else that’s missing too. No mention of the reform – let alone scrapping – of GCSEs, save for the “opportunity to look at further improvements we can make to the examinations that benefit both pupils and teachers”, with the caveat that “any change to GCSEs will protect the principle that rigorous teaching and externally assessed examinations are the best and fairest way to ensure children learn and retain knowledge”. Knowledge, knowledge, knowledge. It’s all about filling the jug.

Grades will continue to be unreliable

Nor is there any mention of the continuing unreliability of exam grades.

On 2 September 2020, Ofqual’s then Chief Regulator, Dame Glenys Stacey, testified before the Education Select Committee that exam grades “are reliable to one grade either way” – implying that a certificate showing “A Level Geography, Grade B” really means “Maybe the grade you merit is a B. But perhaps it’s a C. Or even an A. Nobody knows.”

Nor can anyone ever find out, for this happens even when there are no “marking errors” (surely that really means “failures in the quality control of exam boards”?): as a consequence, this ambiguity cannot be resolved by a “review of marking”.

What use are grades “reliable to one grade either way”?

Unreliable grades do great damage, yet the problem is very easy to fix.

So, in ten years’ time, when students are no longer taking the “gold standard” of A levels, but the rather more downbeat “Advanced British Standard” (or should that be “English”?), the resulting grades are still likely to be only “reliable to one grade either way”.

Tragic.

By Dennis Sherwood, campaigner for the delivery of reliable and trustworthy school exam grades

FE News on the go…

Welcome to FE News on the go, the podcast that delivers exclusive articles from the world of further education straight to your ears.

We are experimenting with Artificial Intelligence to make our exclusive articles even more accessible while also automating the process for our team of project managers.

In each episode, our thought leaders and sector influencers will delve into the most pressing issues facing the FE sector, offering their insights and analysis on the latest news, trends, and developments.

Responses