The missing middle of higher technical learners

Compared to other countries, England has a high share of graduates: almost half of young people now progress to higher education. Yet at the same time, a quarter of working-age adults in England aren’t even qualified to upper-secondary level (A Level or equivalent), which is over twice the level seen in Germany and the US.

Sandwiched in between the two extremes of school-level qualifications and three-year degrees are higher technical qualifications (HTQs). These qualifications, at Level 4 and Level 5, usually involve one or two years of full-time study, and encompass qualifications like higher national certificates and diplomas, many foundation degrees as well as some apprenticeships.

In England, relatively few people take these HTQs. In this article we explain what’s behind this ‘missing middle’ of higher technical learners and why we should be concerned.

Higher technical education in the UK is uncommon

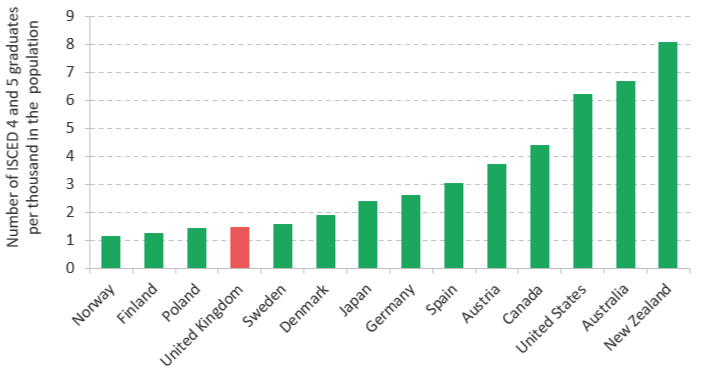

As shown in the chart below, around 1.5 adults per thousand in the UK population complete a HTQ each year, which is lower than most other developed countries. Adults in the United States are over four times more likely to complete a HTQ.

In some countries, Level 4 and Level 5 qualifications are a common educational pathway. Austria and Japan both offer programmes of higher technical education which straddle the upper secondary – postsecondary divide. In the United States, two-year associate degrees are a common pathway to qualify for many professions, including nursing.

The chart above shows the average number of people completing HTQs across the UK, but there is a lot of variation across the country. In Scotland, HTQs are far more common – around one quarter of higher education students pursue the Scottish higher nationals.

Why does the missing middle matter?

The ‘missing middle’ is part of a broader and inequitable polarisation between those who go to university and the rest of the population who select from a set of often low-level technical alternatives to university. These differences in education translate into huge differences in earnings: by the age of 40, the average UK employee qualified to GCSE level or below earns half as much as someone with a degree.

HTQs could offer a way to reduce this earnings gap. A recent report finds that Level 4 and Level 5 qualifications can lead to earnings that compare well with degrees. At the age of 30, the average earnings associated with certain HTQs are higher than the average earnings associated with a degree.

This is not just an equity problem, it’s also a waste of resources. A modern economy throws up many types of job demanding postsecondary education, but it defies common sense to suppose that three years of postsecondary education is necessary for all of them. Skills demands don’t grow conveniently in three-year chunks.

The lack of a clear higher technical pathway

Given that HTQs can lead to decent earnings, it may seem puzzling that so few take them. While there are several reasons, two primary factors are the lack of clear pathways to these qualifications and the availability of funding.

In England, it has been hard to discern a clear role for HTQs. More identifiable selling points are visible in other countries. For example, in Sweden, young adults pursue one or two-year programmes of higher vocational education adapted to local skills requirements with mandatory work placements.

In Singapore, around 20% of the school-leaving cohort with the weakest attainment are directly assigned to two-year ISCED level 4 programmes in the Institute of Technical Education, while another 40% of the cohort, with better attainment, enter polytechnics to pursue level 5 programmes.

In contrast, in the UK there isn’t an obvious pathway from school through to taking HTQs. Learners find it difficult to navigate the wide range of HTQs available to them, which seem to serve different purposes.

The student loan system also inhibits higher technical education

Adult learners usually access government-backed loans to finance their studies. The loan system sometimes used for HTQs (Advanced Learner Loans) is modelled on higher education student loans, but unlike for degrees, maintenance support isn’t available.

Furthermore, loans are subject to the Equivalent or Lower Qualification (ELQ) rule, which means that learners can’t typically access funding for qualifications at an equivalent or lower level to the ones they already hold. For example, someone who has studied towards a degree can’t access student loan funding for a HTQ. This presents another significant barrier to the take-up of HTQs.

The government’s response

To address the ‘missing middle’ we must simplify the existing technical education system and offer adequate funding to those who wish to study HTQs.

The government has recognised the challenges. It has announced that it will restrict funding to a more limited set of approved HTQs which align to employer-set occupational standards. £290M has been devoted to the establishment of Institutes of Technology to deliver HTQs. The existing student loan system is being overhauled and replaced with the Lifelong Loan Entitlement.

All these steps are recent and some important details remained to be resolved, so it is too early to judge whether they are the right measures and will go far enough. We look forward in hope!

By Simon Field, an expert on the international comparison of technical education systems and the author of the ‘Inequality in English post-16 education’ commentary in the IFS Deaton review and Imran Tahir, a research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and an author of the ‘Education inequalities’ chapter of the IFS Deaton Review

Responses