Seven Lenses of Transformation for FE

There is a great deal that college leaders can learn from transformations in other sectors and disciplines which may appear unrelated to further education.

I have always been interested in how insight, expertise, good practice from one area can be applied to another.

I believe both that every sector and organisation is unique, and that it is possible to learn and apply lessons from other sectors and disciplines when thinking about how a given organisation can improve performance and deliver its long-term goals.

Applying lessons and discipline expertise from elsewhere can be incredibly difficult. It requires a deep understanding of the practice, why and how it works in one setting so that its application in another can be properly considered, designed and taken forward.

Doing so effectively is often a matter of understanding the underlying principles of a given discipline or practice, so that it can be deftly applied to a new setting – rather than as a crude transplant.

There are often, also, people and cultural barriers to the effective application of lessons from elsewhere. Colleagues can be precious about the uniqueness of their sector and organisational context – arguing that other sectors and disciplines are too different for parallels to be drawn and lessons learned.

I strongly disagree with such a position; considered on the right, nuanced basis and taken forward deftly, I believe there are great opportunities for leaders in all sectors – including further education – to find new answers and opportunities in the work of apparently unrelated sectors and professional disciplines.

I, therefore, want to invest this chapter in the search for insight from elsewhere, before beginning to think about how leaders might be able to beat the odds, and the system, in transforming further education colleges in the current operating context.

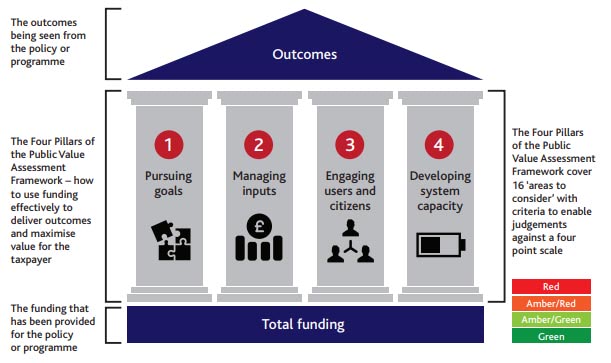

Sir Michael Barber’s public value review offers a useful perspective on how leaders might improve efficiency and productivity in delivering public service goals…

In 2017, Sir Michael Barber completed a ‘public value review’ for HMTreasury – the purpose of which was to identify practical steps that could be taken to improve productivity in the public sector. His report proposes a ‘public value framework’to help government better convert funding into policy outcomes for citizens.

The framework consists of four pillars:

- Pursuing goals: understanding intended outcomes and how progress will be measured; whether those outcomes represent an appropriate degree of ambition; how progress toward them will be tracked; and what data show about historic and future trends.

- Managing inputs: how well public bodies understand the resources available to them; how well they track resource and forecast spending; how effectively they benchmark to identify and secure efficiencies; and how well they understand where a decision taken in one part of government creates cost pressures elsewhere.

- Engaging users and citizens: how well public bodies understand what taxpayers think of them, and how they’re working to improve that understanding; what the user experience looks like, and how public bodies are influencing it; and the extent to which the identity and interests of stakeholder groups are understood.

- Developing system capacity: how well public bodies promote innovation, develop and adopt new technologies and use behavioural insights to improve performance; whether planning and accountability processes support delivery of defined outcomes; how delivery chains are structured; the extent of collaborative working with other public bodies; the quality of a public body’s workforce strategy; and whether public bodies have the systems in place to gather and evaluate performance data.

Barber is careful to note that these pillars are about the process of turning funding into outcomes – independent of any discussion about levels of funding.

Chart 9: Barber’s public value framework

Though pitched primarily as a tool for HM Treasury and government departments to use in taking spending and strategic policy decisions, it is very easy to see how the framework could be used as a tool to help public service delivery organisations – including further education colleges – think about how effectively they are set up to succeed.

The framework includes a series of questions which organisations could use to assess the arrangements they have in place to deliver‘public value’, i.e. the outcomes expected of them.

The ‘pursuing goals’ pillar of the framework is relevant to further education colleges at both strategic and operational levels.

The sector context described in Chapter 1 means that it is incredibly difficult for further education colleges to cut through the noise and define realistic, long-term strategy and objectives; Barber’s framework is an important reminder that, however difficult it is to do, it is incumbent on college leaders to be clear about intended outcomes – because their doing so is essential to the delivery of impactful change.

At the operational level, measuring performance in further education colleges is fairly complicated,to say the least.

Ofsted’s and others’ assessment of college performance cannot be boiled down to a single or even small set of performance indicators; it has long since been recognised that achievement rates alone do not tell a rounded story of performance.

Indeed,the basket of performance measures on which leaders and managers should train their eye is substantial – and varies from programme type to programme type. It can be difficult for colleges to go beyond tracking these measures and begin to analyse them in search of insight.

We saw in Chapter 3 that Ofsted often comments on poorly performing colleges’ insufficient use of data to drive performance improvement. Barber’s framework reminds us of the importance of their doing so.

We also saw in Chapter 3 that poorly performing colleges often suffer from weak financial management and a failure to align resources with their improvement and delivery priorities – which resonates very clearly with the imperatives described in the ‘managing inputs’ pillar of the Barber framework.

Equally, the framework’s reference to understanding how a decision in one part of the system affects another, resonates with government’s tendency to reinvent policy on a rapid cycle and to lumber further education colleges with unfunded mandates.

I am also interested in the ‘developing system capacity’ pillar of the framework. It should be obvious from Chapter 1 that colleges’ capacity and ability to invest in the development of capacity for the long-term are constrained by the resources which are (not) being made available to them by government.

Barber’s framework serves as an important reminder, however, that a focus on what’s next, insight, performance and accountability arrangements are essential to organisational performance in delivering public service outcomes.

Again, the focus on data collection, insight and analytics is notable – and a theme I will return to in Chapter 6.

The Infrastructure and Projects Authority’s seven lenses of transformation offer insights directly relevant to college transformation programmes.

The Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) is the Government’s centre of expertise for infrastructure and major projects.

It has a remit to both support delivery of large, complex implementations and build project leadership capability across government.

It supports delivery of a portfolio of the largest, most complex and challenging implementations in government, including over 140 construction, infrastructure, military, technology and transformation initiatives with a combined whole-life cost of more than £450 billion.

A group of practitioners involved in the delivery of that portfolio of projects developed the ‘seven lenses of transformation’ as a practical guide for understanding and delivering complex transformations.

Both the IPA and Government Digital Service (GDS) use the seven lenses to shape their support to major projects; they also suggest that the framework is equally relevant to organisations of all sizes pursuing major transformation initiatives.

Table 3 summarises the seven lenses: why each of them is needed; how transformation leaders can reflect each lens in their work; some of the trade-offs that each lens entails for transformation programmes and their leaders; and some red flags to watch out for.

Table 3: Summary of seven lenses of transformation

1. Vision |

||

| Clarity around social outcomes of the transformation, and its key themes; compelling picture of the future | ||

| How to do it | Trade-offs | Red flags |

|

|

|

2. Design |

||

| How different components will be configured to deliver the vision; a view of how the whole picture fits together to deliver the vision | ||

| How to do it | Trade-offs | Red flags |

|

|

|

3. Plan |

||

| A roadmap for identifying the sequencing and interdependencies between different elements of the transformation | ||

| How to do it | Trade-offs | Red flags |

|

|

|

4. Transformation leadership |

||

| Creating the right amount of uncertainty to generate ‘productive organisational distress’; bringing together multiple, interrelated disciplines | ||

| How to do it | Trade-offs | Red flags |

|

Transformation leader should:

|

|

|

5. Collaboration |

||

| Involving leaders from all parts of the organisation in the design of shared outcomes; effective collaboration between multiple different groups to deliver the transformation | ||

| How to do it | Trade-offs | Red flags |

|

|

|

6. Accountability |

||

| Clearly defining roles within the organisation and the transformation; knowing who is ultimately accountable for what, empowering people to deliver and holding them to account | ||

| How to do it | Trade-offs | Red flags |

|

|

|

7. People |

||

| Engaging and communicating effectively with the people affected by the transformation; bringing people impacted by the transformation on the journey | ||

| How to do it | Trade-offs | Red flags |

|

|

|

The framework is deeply relevant to the transformation of poorly performing further education colleges – not least given how directly it resonates with the analyses presented in Chapters 1, 2 and 3.

There is nothing about further education colleges which means this generalised transformation cannot be – deftly – applied to their transformation.

It is interesting to see that the red flags described with respect to the ‘vision’ lens are very similar to the weaknesses which Ofsted often identifies in poorly performing colleges and/or issues which are often the focus of FE Commissioner recommendations, i.e. a lack of ambition; a lack of clarity around and action to address areas for improvement; and the need for stronger focus on the student experience.

The seven lenses framework describes vision as a matter of‘clarity around [the] social outcomes of the transformation, and its key themes’.

I will argue in Chapter 5 that clarity around organisational purpose,strategy and values is the platform on which any transformation should be built.

I am also interested in the lenses focused on ‘design’ – ‘how different components will be configured to deliver the vision’ – and ‘plan’ – ‘a roadmap for identifying the sequencing and interdependencies between different elements of the transformation’.

I will talk more in Chapter 6 about the importance of a robust, detailed and communicable plan – and the wider merits of an operations excellence mindset in delivering transformation.

Again, there is clear resonance between the red flags described in relation to these two lenses, Ofsted’s common criticisms and the FE Commissioner’s common recommendations, including the seven lenses’ references to:

- Losing sight of transformational outcomes

- Focussing on the parts of the design that people are comfortable with, rather than doing what matters’; and

- Not having appropriate governance

The other two lenses which I would like to draw attention to, at this point, are those relating to:

- Transformation leadership – ‘creating the right amount of uncertainty to generate productive organisational distress’ – and

- People – ‘engaging and communicating effectively with the people affected by the transformation; bringing people affected … on the journey’.

I will talk much more about both of these themes in Chapters 5 and 7. The suggestion that leaders must be able to generate ‘productive organisational distress’ is very interesting.

It is clear from Ofsted’s common criticisms and the FE Commissioner’s common recommendations that poorly performing colleges are not always sufficiently live to the issues they face, and are not always taking rapid, focused and decisive enough action to address those issues.

The notion that leaders need to create a degree of disruption to spark the change process resonates very clearly with my and others’ experience.

On the other hand, we saw in Chapter 1 some of the many examples of the pressure colleagues working in further education are under – and the impact that is having on their health, wellbeing and willingness to continue working in the sector.

In thinking about how they generate necessary disruption, leaders in further education must also have a very strong sense of the level of disruption that the organisation – and those working within it – can cope with.

This is a very fine balancing act in the current sector context. The seven lenses framework’s suggestion that transformation and business-as-usual roles require different skillsets is an important point – as are the red flags about having people carry out transformation roles whilst maintaining responsibilities for business-as-usual work; and having the same ‘usual suspects’ working on every critical project.

The challenging financial context in further education makes it very difficult for leaders to supplement their existing teams with the additional people and expertise required to drive successful transformations.

Matt Hamnett, Director, MH+A

Over the next few weeks FE News will be publishing this research in full, and FETL will be hosting a webinar with Matt on the report later in February.

Chapter One: The further education operating context is incredibly tough / The introduction of T levels

Chapter Two: College performance compared to other sectors

Chapter Three: The 5 causes of poor performance in FE

Chapter Four: Seven lenses of transformation for FE / FE Can Learn From The Success Of Other Sectors

Chapter Five: Good Strategy Is Crucial For FE Transformation / Policy Cycle Blights FE: Colleges Leaders Should Chart Their Own Course

Chapter Six: How to unleash the talent already in your college / Aligning organisational purpose, strategy and transformation priorities with available funding

Chapter Seven: Leading the transformation in FE

Responses