Action needed to avert the growing crisis in language learning

The @HEPI_news Higher Education Policy Institute’s latest report, A Languages Crisis? (HEPI Report 123) by Megan Bowler, highlights a huge drop in demand for learning languages and makes a set of recommendations for reversing the fall.

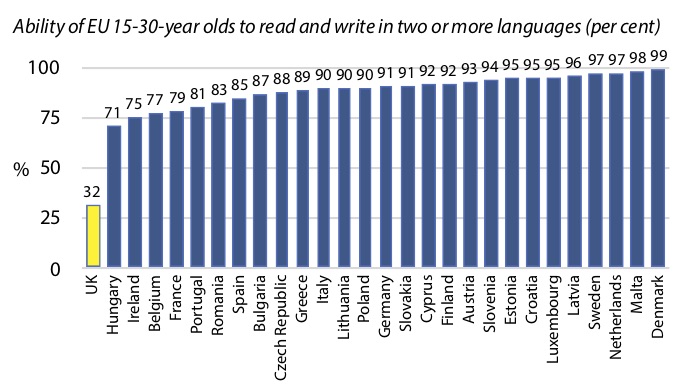

The paper shows only 32 per cent of 15-to-30 year olds from the UK can read and write in two or more languages (including their first language).

This is less than half the level in the second-placed EU country (71 per cent in Hungary), and far behind France (79 per cent), Germany (91 per cent) and Denmark (99 per cent).

The report includes 15 recommends for addressing the challenge, including:

- ensuring more varied GCSE and A-Level courses;

- making a foreign language compulsory at Key Stage 4 (KS4), with accreditation (either a GCSE / National or alternative vocational or community language qualification) encouraged but optional.

- increasing teaching staff numbers through new measures, such as conditional financial incentives and including all language teachers on the Shortage Occupations List; and

- where tuition fees exist, supplementing fee income with additional government funding to safeguard minority languages and facilitate free additional language-learning for students and staff.

Megan Bowler, the author of the report, is a third-year Classics undergraduate at the University of Oxford. She said:

“The cultural and political implications of Brexit mean it is more urgent than ever that we re-evaluate our attitudes towards languages. Learning a language develops an analytical and empathetic mindset, and is valuable for individuals of all ages, interests and abilities.

“It was a big mistake to scrap compulsory foreign languages at GCSE. Rather than continuing to present languages as not suitable for everyone, we need to include a broader range of pupils learning through a variety of qualifications geared to different needs.

“Given the shortage of language skills in the workforce, we should safeguard higher education language courses, particularly those involving less widely-taught languages, and prioritise extra-curricular language learning opportunities for students from all disciplines.”

Nick Hillman, Director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, said:

“The decision to limit language learning in schools by making GCSE languages voluntary is probably the single most damaging education policy implemented in England so far this century. The UK is bottom of the pile for the number of young people familiar with another language, and miles behind every EU country.

“The problems this has caused are now hitting university Languages Departments hard. Student numbers for French and German have almost halved since 2010 and, for Italian, they have fallen by around two-thirds.

“Boris Johnson is the first Prime Minister since Harold Macmillan to have studied Languages at university. So we hope he will adopt some urgent new policies to encourage a love of languages and to show to the rest of the world that post-Brexit Britain will not cut itself off from the rest of the world.”

Vivienne Stern – Director of Universities UK International – said:

“This report adds to previous evidence of declining student numbers in some humanities subjects and particularly in languages. With the government yet to commit to either continued access to Erasmus+ or an alternative fully-funded national scheme after Brexit, there could be further reductions in the number of students enrolling onto modern language courses.

“In our Solving Future Skills Challenges report Universities UK noted that demand for higher level skills is increasing across a range of levels and subjects, and with an overall shortage of graduates, a strong base of language skills is required not only to meet the needs of employers and our economy, but for the success of our culture and society.

“Along with partners including the British Academy, we believe there is a need for a national languages strategy and would welcome the opportunity to work with government on what this could involve.”

Bernhard Niesner, CEO and Co-Founder, Busuu comments:

“Language learning in the UK is a broken system that we desperately need to fix – especially in light of Brexit. The fact that less than a third of young Britons can read or write in more than one language, whereas the large majority of youngsters in France and Germany are able to, proves that learning a language in a traditional setting is too complicated.

“Beyond simply incentivising students by boosting grades, the UK needs to do much more when it comes to giving both teachers and students access to the tools and technology that enable language learning to be more enjoyable and effective.

“The UK also needs to do a much better job when it comes to selling the wider benefits of learning a language – rather than just motivating students to pass an exam or to get a GCSE. There is already a shortage in language skills in the workforce, and if the younger generation progresses this trend, it will affect the UK’s future business success.”

Kirsten Campbell-Howes, Head of Education, Busuu comments:

“At Busuu, we’ve see the number of UK language learners on our platform more than double in the last year, reflecting strong demand from British people to understand and communicate in foreign languages – particularly Spanish, French and German. Anything that the UK can do to boost opportunities and enthusiasm for language learning is, therefore, a major step forward.”

Megan Bowler is a third-year undergraduate studying Classics at Oriel College, Oxford. During vacations, she tutors in Latin, Ancient Greek and English and she recently completed an internship at HEPI.

Responses