NEU State of Education – Mental Health of Young People

In the latest survey of over 8,000 National Education Union members, conducted ahead of Annual Conference in Bournemouth, we asked teachers and support staff about the mental health of young people.

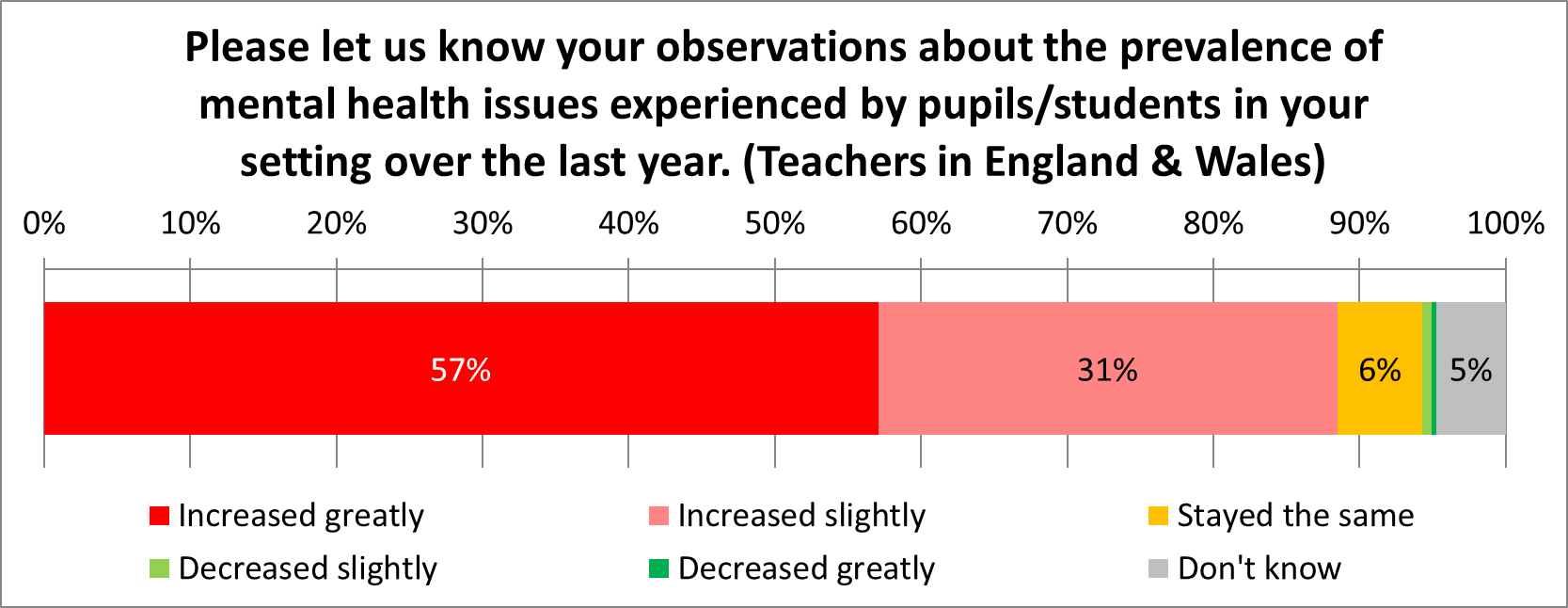

- 88% of teachers tell us that they have seen an increase in the prevalence of student mental health issues over the last year, with 57% saying it has increased greatly in that short period of time.

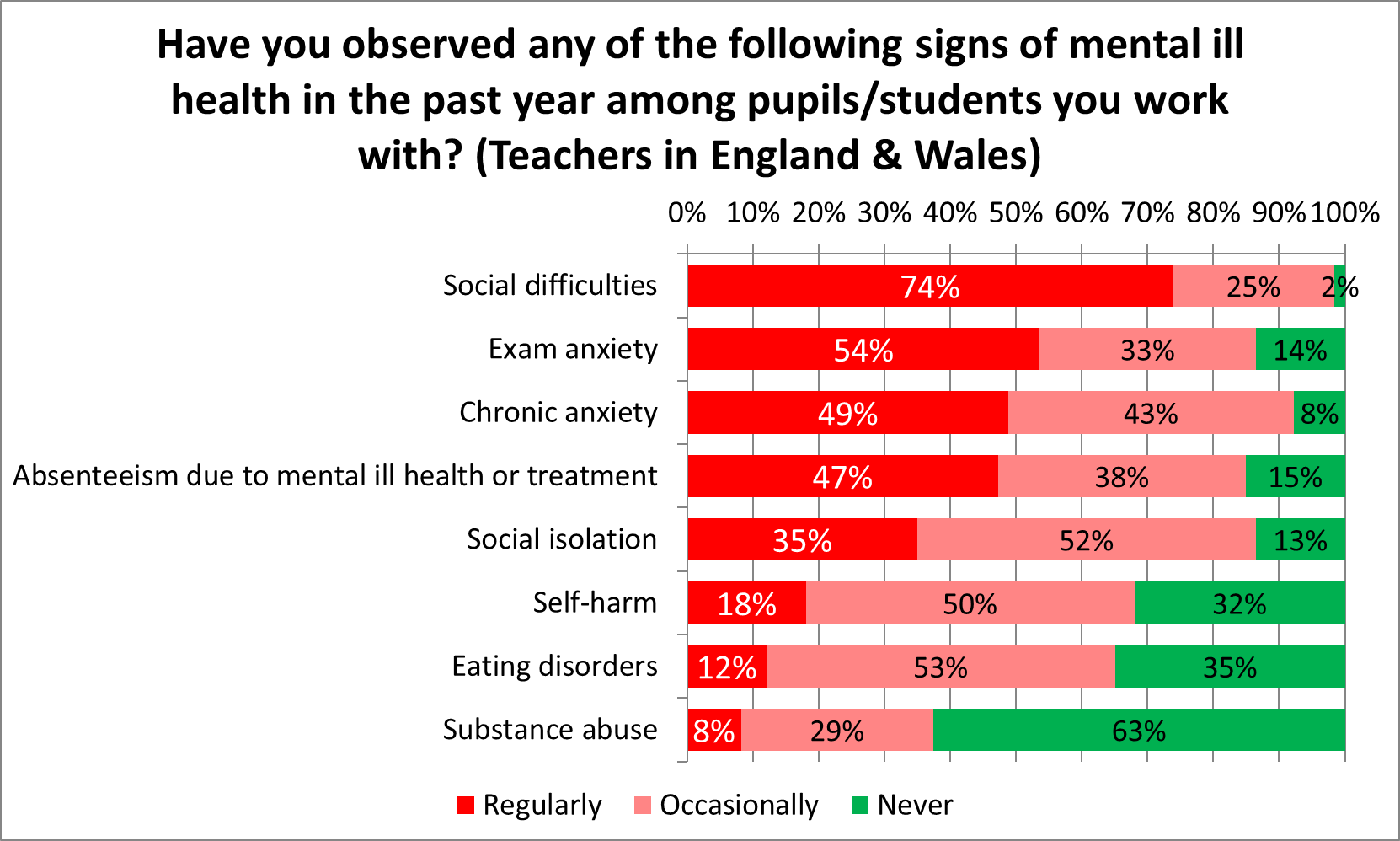

- Half or more told us that pupils are regularly displaying chronic anxiety (49%), exam anxiety (54%) or absenteeism (47%) as a result of mental ill-health. Three quarters identify general social difficulties among pupils (74%).

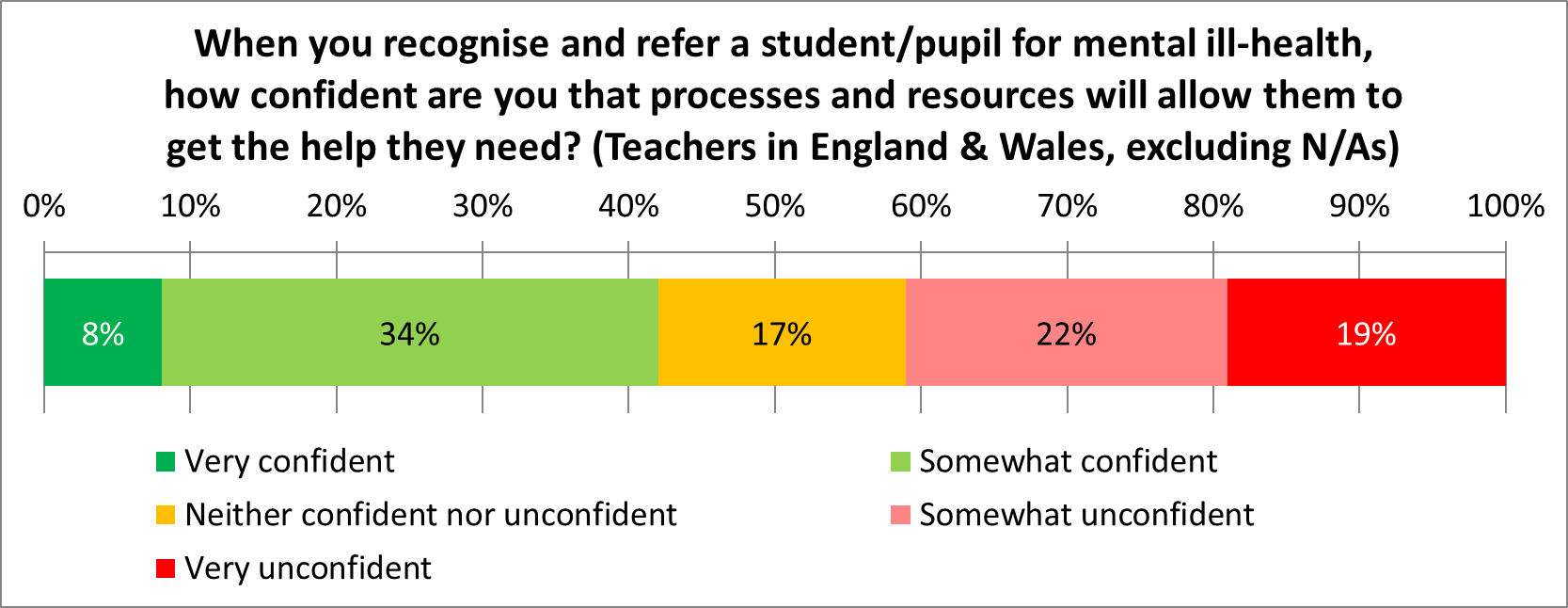

- There is a divided faith in the system of referral, with just 42% telling us they have confidence that their pupils will get the help they need from existing processes and resources. One in five said they are “very unconfident”.

The State of Education survey gauges the views of working teacher, support staff and school leader NEU members in England and Wales. We are releasing the findings over the course of Annual Conference.

Prevalence of Mental Health Issues

Members responding to our survey were emphatic in their view that mental health issues are on the rise among pupils/students.

A combined 1% told us that mental health issues have decreased in their setting in the past year. Very few (6%) felt they have stayed the same. The resounding message from the vast majority (88%) is that this is a growing issue within their school.

When we last asked this question, in 2022, we had only recently emerged from the pandemic. Back then, when asked how the prevalence of mental health issues in their school compared to before Covid, 90% of respondents said that it had grown. That almost as many (88%) are saying the same for 2023-24 should raise alarm bells in Whitehall.

Respondents told us:

“The entire primary population has poorer mental health, poorer social skills and less developed language when compared to, say, five years ago. Pupils find learning harder as a result, but the curriculum demands don’t budge.”

“My experience of mental health has increased. Pastorally, this is mostly what I deal with. Self-harm continues to be a problem, with little or no intervention from CAMHS because most students don’t meet the ridiculous threshold. I have had two students in the past two years attempt suicide. Teachers need mental health training because we are often the people who notice first or who students come to.”

“It feels like I have to be a therapist every day at work; I am talking kids down and trying to manage severe emotional issues just to get students to sit down and work on the lesson task. I have not received any training on mental health work and can only go by personal experience and books I have read in my spare time. It takes a real toll on staff.”

Another added that “10 years ago we had counsellors and therapists available in schools to help those children. We had staff trained to run social-emotional interventions to help, and now we have none.”

Next, we asked members to reflect on what signs of mental ill-health they have spotted amongst pupils in the past year.

Three quarters (74%) told us that social difficulties are a regular issue, with a further quarter (25%) describing them as occasional. This led the results, although around half also identified chronic anxiety (49%), exam anxiety (54%) and absenteeism in relation to mental ill-health or treatment (47%) as regular factors. There were significant responses for self-harm and eating disorders, as well, with two-thirds saying they had witnessed both in the last year.

Among English state secondary teachers, exam anxiety is at 78% regularly and 21% occasionally (only 1% never); chronic anxiety is at 60% regularly, 37% occasionally; self-harm is at 34% regularly and 61% occasionally; and eating disorders are at 17% regularly and 65% occasionally.

External Assistance

Whereas a school should feel confident that a referral on grounds of mental ill-health will result in help for a student, this is not always the case. Respondents to our survey expressed a mixed view on their faith in the system.

Just 8% expressed great confidence, with 19% saying they are “very unconfident” that the help needed would arrive through the existing systems of external support. Net confidence (42%) is only slightly higher than a net lack of confidence (41%).

This mood is not without foundation. Last month, the Children’s Commissioner published new statistics showing the scale of the challenge. In England in 2022/3, of the near one million young people (949,200) with active referrals for Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services, just 32% received support. Over a quarter of those who have been referred (28%) were waiting for support, while 40% have seen their referral closed without any support. Overall, the 949,200 referrals accounts for 8% of all 11.9 million children living in England.

These comments from respondents help to cast light on why there is such a divided view about the existing support system.

“I am confident the pupils will be supported in school but very unconfident they will receive the necessary support from the state/council/within the community.”

“Support services very slow to respond. Problem escalates whilst waiting, rather than being nipped in the bud.”

“Speech and language delay has definitely got worse over the years. There are less educational psychologists and less Speech and Language specialists, mostly due to funding and pay that hasn’t caught up. Mental health services are pretty much non-existent. This is something teachers can’t ‘make do and mend’ because we just don’t have the expertise.”

A support staff respondent told us, “Referral times for very serious issues are a joke. CAMHS hugely underfunded/short staffed. You can refer someone in Year 8/9 and they won’t see anyone until they’ve left school!”

“Our school children have NO access to speech and language support, NO access to occupational therapy and to enable a child to access emotional support through referral is exceptionally hard.”

“It feels almost impossible to get support for students; funding and services are being cut and waiting lists are so long as to make referrals almost pointless. Schools are expected to deal with it but are given neither the time nor resources to do so.”

“The system is broken. Students have to be ‘actively’ suicidal to get a CAMHS referral.”

“Crisis in mental health now falls upon the schools due to excessive wait times at CAMHS and GP. We are not resourced or qualified for this. Wellbeing roles are hard to recruit for and retain due to horrendous pay.”

“It is almost impossible to access mental health resources outside of school. [We regularly see] doctors requesting the school provide mental health support to children/families instead of referring to CAMHS. We are expected to provide this with ever diminishing budgets.”

Commenting on the findings of the survey, Daniel Kebede, Joint General Secretary of the National Education Union, said:

“Support services for mental health are under an incredible strain, and the system is clearly buckling. Young people end up in a referral limbo which may not resolve itself until they are months or even years down the line. In the meantime, schools are asked to improvise ways of managing this distressing situation.

“Mental health issues can be lasting if unattended. It is clear to everyone, surely, that a child’s education journey is a vital part of their life and it should be properly resourced and staffed so that they are supported every step of the way. Instead, we have a Government content to starve local services, cut school funding in real-terms so specialist staff cannot be afforded, and preside over an increase in absenteeism as a direct consequence of mental ill-health.

“The Government must now move heaven and earth to get these waiting times down and equip schools and local authorities with the staffing and resources to close this enormous gap. A good start would be to accelerate the rollout of mental health hubs across the country.”

Responses